Click to enlarge

FIG. 121-3.

AMONG modern amulets, used specially and avowedly against the evil eye, the cross finds no place; for the simple reason that it has taken its position as the great Christian symbol, whereby its connection with times preceding Christianity has been severed, and its meaning modified to its later purpose.

Of all simple signs it is the easiest to make and the most common, whether ancient or modern. In these latter days it is often but a mere mark, like the chalk cross made by an artisan upon his work, or the sign-manual of our parish marriage register, yet in many of its forms and uses it has a very distinct and special meaning.

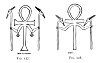

Among the ancient Egyptians the cross was very common. Standing on a heart (as in Fig. 121) it was the symbol of goodness 422; the same form in hieroglyphic writing is the ideograph nefer or the phonetic n. 423 It is shown thus on a tablet depicted by Maspero 424 together with a Calvary cross. These tablets (dalles), found in considerable numbers, were slabs of stone, whereon were sculptured models, to teach the apprentices their trade

and they show examples of stone carving in all stages from the mere outline to the finished work.

At the Ashmolean Museum are undoubted amulets from ancient Egypt, such as Figs. 121, 122. Quite as ancient as any of these is a small ornamental cross

Click to enlarge

FIG. 121-3.

amulet of gold, found by Schliemann in the third sepulchre at Mycenæ, now in the Athens Museum (Fig. 123) 425 rather suggesting serpents in combination. Several other cross ornaments were found in the same tomb, but they are not of this distinct character. We are told that the Spanish conquerors of Mexico were astonished at finding the cross in common use by men whom they knew to be heathens, and that they managed to ingratiate themselves with the natives by displaying the cross upon their standards. Many crosses appear also on the ancient Peruvian hieroglyphs (Fig. 126).

What the true symbolical meaning of the cross may be, is a vexed question. On the one hand, many hold it to be distinctly phallic; in India it is always so considered, while others say the "theory is monstrous and devoid of evidence." 426 All authorities, however, agree that the T or tau

cross is the symbol of life 427 in both its forms, i.e. either the simple T or with the loop handle attached. The latter is the crux ansata or ankh, seen in the hand of most of the Egyptian gods of the later period. In one or other of these forms it is traditionally held to have been the mark set upon Cain; also upon the houses of the Israelites in Egypt, to preserve them from the destroying angel.

The rod Moses stretched over the Red Sea and with which he struck the rock is supposed to have been topped with a cross; on the Tau the brazen serpent was upraised. Mediæval writers thought the two sticks gathered by the widow of Sarepta a type of the cross; but in Ezekiel ix. 4 the mark to be set on "the foreheads of the men that cry," etc., was certainly the T; for the Vulgate has: "Et signa Thau super frontes virorum gementium." Many authorities accept this rendering: St. Jerome "refers again and again to this passage"; SS. Cyprian, Augustine, Origen, and Isidore allude to it; also Bishops Lowth and Münter; "but there need be little doubt as to the passage." 428

In the roll of the Roman soldiery after a battle it was customary to place T against those who were alive, and Θ against the killed.

In the Roman Catacombs is found the T or St. Anthony's cross; in those very early days of the Church it symbolised the belief in the eternity of that life upon which the departed soul had entered. This was probably the transition period, when the cross had not yet been fully recognised as the special symbol of the Christian faith.

The ancient Britons worshipped the T or Tau as a god, and among Northmen of old the same figure was "the hammer of Thor," the Scandinavian Jove; reversed thus

, it is the yoni-lingam symbol of the Hindoos. 429

, it is the yoni-lingam symbol of the Hindoos. 429

The crux ansata form is exceedingly

Click to enlarge

FIG. 124.-125.

wide-spread. 430 Not only is it found in the sculptures from Khorsabad, from Nineveh, and in the Palmyra sculptures now in the Louvre, but further east in Persia and India. More remarkable still is it to find the same sign in far-distant Peru, where it appears as an actual shape cut through great blocks of granite (Figs. 124, 125), both ancient and modern at Cuzco, and also in the remarkable hieroglyphics of the Incas reproduced in Fig. 126. 431 The ancient Cuzco block at the time of the Conquest was used for the execution of criminals. The head was inserted face down in the round aperture, and a piece of wood jammed into the slot so as to hold the neck tight; the body was then seized, violently lifted, and the neck dislocated. 432 There are no means of ascertaining what the Incas intended by this crux ansata, but the fact remains that it existed, and is found repeatedly in ancient Peru. The cross was known in South America in several other forms besides the ankh, as appears from the hieroglyphics of Peru.

Click to enlarge

FIG. 126.--From Wiener, Pérou et Bolivie, p. 775.

A device almost exactly similar 433 is found on coins of Asia Minor, Cilicia, and Cyprus. It is placed on a Phœnician coin of Tarsus beneath the throne of Baal. Another is on a Sicilian medal of Camarina.

It is, however, in Egypt that this symbol, sometimes called the Cross of Serapis, 434 is most commonly to be seen in the hands of kings and gods alike. One scene 435 represents Amenophis II. having a double stream of these figures, alternated with the symbol of purity, poured out upon him by the gods Horus and Thoth. This same act is also a subject of sculpture at several places, and by the outpouring of life and purity denotes the king's purification, to fit him to stand before the god of the temple. In each case the king so purified also held the ankh in his right hand. 436

Besides these, the same cross is in a way personified with arms and hands holding the symbol of purity. Especially were these noted by the writer at Medinet Habou and at Edfou (Figs. 127, 128). At both these temples the figures are repeated in rows, side by side, so as to form a decorative dado.

The meaning of the crux ansata wherever found is testified "in the most obvious manner," 437 denoting fecundity and abundance in the way universally understood by this symbol throughout India. 438 And

we may remark that the use of this cross as the symbol of fertilisation is perfectly consistent with the sign being that of the kind of life therein typified. 439

All these examples are of ancient usage, but there

Click to enlarge

FIG. 127., 128.

will be little difficulty in showing that it has been used throughout the Middle Ages, and that it is found today in a form but slightly modified. At the present day in Cyprus the women wear this cross as a talisman. 440 It is believed to keep off the evil eye and to prevent or cure barrenness.

Fig. 129 is a coin of Ethelward: 441 besides a smaller one in the inscription, there is a cross on the centre of each side; one of these is the crux ansata in a form which is still more "obvious" than that usually seen in the hands of Egyptian gods or kings, or even upon the Indian Iswara.

[paragraph continues] The object of a cross on each side of this coin was the customary one, of placing protective amulets against the evil eye upon coins, medals, and seals, as well as upon buildings, public and private. One of these amulet seals, having the sun and moon upon it, was in actual use by the Dean and Chapter of St. Andrew of Wells (Fig. 137),

Click to enlarge

FIG. 129.

down to a comparatively late period--long since the Reformation. A careful consideration of the coin of Ethelward will help us to understand its later developments, especially if we look upon both crux in corde (Fig. 121) and ansata, undoubted amulets for suspension, as practically the same things; for we cannot fail to see that all the devices are but modified forms of one and the same symbol. On a cylinder from Babylon 442 there is a figure holding a crux ansata, reversed from its usual Egyptian position, and having the cross upwards and the ring beneath.

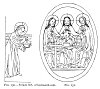

Our next stage is shown in Fig. 130 where the Third Person of the Holy Trinity, the "Lord and Giver of Life," holds this same symbol, but slightly changed, in His hand. Again, in Fig. 131 the Father Almighty holds the same symbol under His left hand. The only difference is that in both of

these examples the cross is upon the globe as well as above it. 443

On a bas-relief from the Roman Catacombs is a representation of the Lamb, but instead of the usual flag He holds a staff, with a ball and cross on the

Click to enlarge

FIG. 130., 131.

top, precisely like the conventional orb and cross in the hand of kings and queens. 444 The historic gradation of the use, from remote ages to the present day, of this symbol of life in perpetuity as the badge of sovereignty, makes it clear, however unwilling

devout worshippers of royalty may be to assent, that the object we know so well as the orb and cross, is nothing else but a powerful amulet against the evil eye.

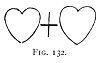

Those who remain sceptical as to our chain of facts will perhaps be convinced by the following. In days when brewing used to be done at home, the writer, as a boy, has often watched and helped the operations. When the malt was steeped in the "mashing vat" our old man used to cover it up with cloths "to let it steevy"; but before doing this he never failed "to zet the kieve."

Click to enlarge FIG. 132 |

amulet of the same identical elements as that on the coin of Ethelward; for by merely bringing the two hearts together, and slightly rounding them, with the cross placed on the top, we have the "obvious" figure itself.

Whatever may have been the notion of the designers of St. Peter's in Rome and St. Paul's in London, the fact remains that each of these great Christian churches bears on its highest point the orb and cross of royalty, no other than the crux ansata (a symbol of the perpetuation of life in one aspect, and a potent amulet in another), raised high above the people, like the famous cricket of Pisistratus at Athens, the crocodile at Venice, the devils on Notre Dame, and the diavolo at Florence, protecting them from the wicked glance of the evil spirits expected to lurk around when the bells are silent. Of course all this will be set down as pure speculation; but of such cavillers we would ask, first for a better explanation of the ball and cross, and next for any explanation whatever of the maintenance of bells other than that they represent an ancient custom, founded, like the orb and cross, on an ancient belief. 446

That the cross was actually worn as an amulet in ancient times is clearly proved by the fact that two

men called Kharu (Syrians) appear on Egyptian sculptures actually wearing it suspended to the neck. 447

At the British Museum may be seen a large cross amulet suspended from the neck of Tiglath Pileser in the great tablet from Nimroud. At this day necklaces made of a string of crosses are worn by the Indians of Peru, 448 but these latter may be from Christian sources, though that is by no means even probable.

There are other kinds of cross among the variety used in heraldry or ornament, which certainly have a mystery about them, and some of which are amulets. 448a Foremost among these is the svastika of the Hindoos, the fylfot-cross or gammadion, called also by some the "catch L,"

Among the Hindoos this was the mark or sign of Vishnu, 449 the beneficent preserver of life. It is proved now to be a sun symbol, by Mr. Percy Gardner, who has found a coin of the ancient city of Mesembria in Thrace, on which is the fylfot with a sun on its centre. The name of the place means the city of "Mid-day," and this name is also figured on some of its coins by the legend ΜΕΣ.

, 450 which clearly and decisively proves its meaning. This form of cross was early adopted among Christian symbols, for it is found in the Roman Catacombs of

, 450 which clearly and decisively proves its meaning. This form of cross was early adopted among Christian symbols, for it is found in the Roman Catacombs of

the fourth century. 451 As a mystic sign it is said to have travelled further than any other symbol of antiquity. 452 It was known in Iceland in the ninth

Click to enlarge

FIG. 133.

century; it is known all over Asia, including Japan;

all over Europe from Iceland to Greece, Sicily, and Malta. It is found on the oldest Greek coins, on Etruscan vases, and on the Newton Stone, an ancient Celtic monument at Aberdeen. 453 Comte Goblet traces it to the Troad as its birthplace, some thirteen hundred years before Christ. Schliemann found at Mycenæ a terra-cotta dish, on one side of which "are engraved a number of

s, the sign which occurs so frequently in the ruins of Troy." 454 He says the same sign was often found on vases and pottery. 455

s, the sign which occurs so frequently in the ruins of Troy." 454 He says the same sign was often found on vases and pottery. 455

From its appearance on coins and from its being a sun sign we may accept the conclusion that the

Click to enlarge

FIG. 134.

fylfot was an amulet against the evil eye "of wonderful diffusion." We are told that the triskelion or triquetra is a modification of the fylfot, and that it was adopted as the badge of Sicily by Agathocles about 317 B.C. and later by the Isle

of Man. 456 We are told 457 that the arms of Sicily and the Isle of Man consist of three human legs of identical pattern, except that the latter are

Click to enlarge FIG. 135. |

277:422 Wilkinson, vol. iii. p. 352.

277:423 Budge, Nile, pp. 55, 65.

277:424 Arch. Egypt. pp. 190, 191.

278:425 He (Schliemann, Mycenæ and Tiryns, p. 66) says: "The cross with the marks of four nails may often be seen" upon vases and other pottery.

278:426 Baring-Gould, Myths of the Middle Ages, p. 358.

279:427 Budge; Wilkinson; Baring-Gould; Smith, Dict. Bib. etc., wherein many ancient authorities are quoted, forming the basis of modern research.

279:428 Baring-Gould, op. cit. p. 377.

280:429 Much discussion has taken place from time to time as to what was the real shape of the cross on which our Lord was crucified. The famous graffito found on the Palatine, now in the Kircherian Museum in Rome, seems to settle the question. Whether it is an actual blasphemous caricature, as most people believe, or whether it was, as King (Gnostics, p. 90) says, "the work of some pious Gnostic, of his jackal-headed god," is the question. A close examination of the photographs or of the original shows that the man who scratched it used two strokes to form T, and that he afterwards added a short one over, to carry the superscription; for the line is perfectly distinct from the main upright line of the cross. Had he not been accustomed to the tau cross and none other, as the one with which he associated crucifixion, he would not so carefully have made his down stroke exactly meet the horizontal one, but would, as we should, have begun at the top, some way above the line of the arms. A comparison between King's plate, p. 90, and a photograph from the original, will show very clearly what we mean, In King's, the upright line is continuous from the superscription to the feet. In Lanciani, Ancient Rome, p. 122, is a photogravure which completely confirms the writer's own close observation, and enables him entirely to dispute Mr. King's explanation. In the photographs from the original, there is nothing to suggest the head of a jackal; it is even in his own drawing distinctly equine. Moreover, being in Rome a very short time after the find, the writer saw, and knows well, the spot whence the whole piece of plaster had been removed to the Museum, and there close by on the same wall was another graffito, possibly by the same hand, of a donkey turning a conical mill-stone with a plain inscription, p. 281 which read, Labora asine, etc. This has also been removed. Inasmuch as the graffito is known to have been almost contemporary (A.D. 69) with the event depicted, it forms a most convincing link in the chain of evidence that our Lord suffered upon a tau cross. The spirit which would lead to such a graffito as that here discussed is abundantly exhibited in Acts xxviii. 22. Probably it was drawn while St. Paul was in Rome, when "this sect" was spoken against.

281:430 This subject is treated at great length by an anonymous writer in a volume called Phallism (London, privately printed, 1889), but his facts are different, and do not lead to the same conclusion as those here produced.

281:431 A close examination of these inscriptions shows a strange general resemblance to Egyptian characters. It will be noticed that the cross in various shapes is very frequently used. The writing here reproduced is reduced to one-fifth; the original is now in the Museum of Cuzco. Wiener says that although written about the end of the sixteenth century, the style and characters are those used before the Conquest. The document was found in the valley of Paucastambo, "dans le pays perdu de la Bolivie, à Sicasica."

281:432 Wiener, Pérou et Bolivie, p. 724

283:433 Baring-Gould, op. cit. p. 362, who gives illustrations (Figs. 19, 20, p. 344) and quotes Raoul Rochette, Mém. de l'Academie des Inscr. tom. XVI.

283:434 Payne Knight, Symbol. Lang. p. 238.

283:435 Wilkinson, Anc. Egypt. iii. 362.

283:436 In Fig. 103 it will be noticed that one of the Sun's hand-rays is holding the symbol of life to the lips of Khuenaten. In the other plate referred to (Wilkinson, i. 40) two of these same hand-rays are holding the ankh to his lips and to those of his wife.

283:437 C. W. King, Gnostics, p. 72.

283:438 Ardanari Iswara is represented (Forlong, Rivers of Life, vol. ii. p. 374. Pl. xiv.) as a female standing on a water-lily with the crux ansata as her only p. 284 ornament. Her right hand is raised in the position on which we have more to say--that of the mano pantea.

284:439 "In solemn sacrifices all the Lapland idols were marked with the ♀ from the blood of the victims. . . . It occurs on many Runic monuments in Sweden and Denmark long anterior to Christianity."--Payne Knight, Symbol. Lang. p. 30. One author (Forlong, op. cit. i. 317) asserts that this symbol was adopted as the ancient pallium, which was shaped thus. He gives an illustration of it, as worn by a priest.

284:440 General di Cesnola, Cyprus, p. 371.

284:441 From Archæologia, vol. xix.

285:442 Münter, Religion der Babylonier. Köpenhagen, 1827.

286:443 Wilkinson, vol. ii. p. 344, gives a number of necklaces made up of amulets such as we have dealt with. Among these is a large scarab with the T cross upon it, just as is seen upon the orb in the hand of the First and Third Persons of the Holy Trinity, Figs. 130, 131. See also Fig. 141.

286:444 These figures are from Symbols of Early and Mediæval Christian Art by Miss Louisa Twining, to whom I am indebted for kind permission to reproduce.

287:445 The same thing was done all round the countryside when people used to bake at home. The barm put into the dough is called "setting the sponge." The batch is then lightly covered and left all night "to rise." It is at this time that the "two hearts and the criss-cross" were and are made upon it, precisely similar in kind, and for the same purpose, as upon the mash in brewing, or on the seed-bed. It is of course to this old custom that Herrick refers in his Hesperides:

This I'll tell ye by the way,

Maidens, when ye leavens lay,

Crosse your dow, and your dispatch

Will be better for your batch. p. 288

In the morning when ye rise,

Wash your hands and cleanse your eyes.

Next be sure ye have a care

To disperse the water farre;

For as farre as that doth light,

so farre keeps the evil spright,

288:446 This belief is not merely a superstition of the early or mediæval Church, but of much more ancient times. Bells were adopted from heathendom by Christians, though they have been rejected by Mahomedans.

"Temesæaque concrepat æra

Et rogat ut tectis exeat umbra suis."

Ovid, Fast. v. 441-2.

289:447 Wilkinson, Anc. Egypt. i. 246.

289:448 Wiener, Pérou et Bolivie, p. 667.

289:448a Those especially known as fleurie, and fleurettée, have each limb tipped with the fleur-de-lis, while the cross botonée is tipped with the fig-leaf. Both of these fantastic ornamentations have distinctly phallic meanings which add power to the cross as an amulet. See Inman, Anc. Faiths, pp. 150-165.

289:449 C. W. King, Gnostics, p. 229.

289:450 Goblet d'Alviella, Migr. des Symb. Athenæum, No. 3381, p. 217. See Letter from Prof. Max Müller, Athenæum, No. 3382. Also R. P. Greg, On the Meaning and Origin of the Fylfot and Svastika. 1884.

290:451 Brownlow, Roma Sotteranea, vol. ii. p. 177.

290:452 It occurs on an old stone cross in company with Ogham inscriptions at Aglish (J. Romilly Alien, Christian Symbolism. p. 97) in Kerry. On these the arms are reversed so as to make it appear to turn against the sun. In King's Gnostics the svastika is shown both ways.

291:453 King, Gnostics, p. 176.

291:454 Mycenæ and Tiryns, p. 77. This would put the date indefinitely further back than Comte Goblet does.

291:455 Ib. p. 66.

292:456 On an ancient Etruscan vase found at Volci, now in the Museum of Rouen, is a scene representing a fight between Athena and Enceladus. On the shield of the fallen giant is the triskelion: the legs are naked, meeting in the centre, without the Gorgoneion (Daremberg et Saglio, p. 102).

292:457 Goblet d'Alviella, op. cit. Athen. 3381, p. 217.

292:458 From History of Malta, Boisgelin, 1805, p. 18.

292:459 King, Handbook of Gems, p. 361.