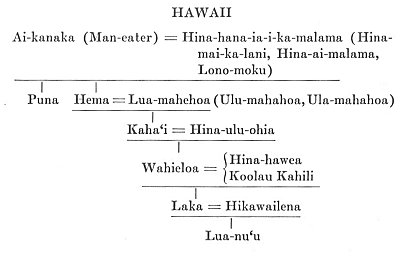

THE Ulu genealogy used by the chiefs of Maui and Hawaii includes, as the twenty-eighth to the thirty-second in descent from Wakea, the names of five chiefs famous also in the genealogies and tradition of the South Seas. These five are Ai-kanaka (Kai-tangata), Hema, Kaha‘i (Tawhaki), Wahieloa, Laka. A comparison with southern groups shows a close likeness in the series, although the names of their wives differ widely.

The district of Hana in East Maui is the center of localization in Hawaii for the lives of the Aikanaka-Laka family, and traditional chants are preserved which tell precisely where each of the five was born, where the afterbirth, umbilical cord, and navel string of each were buried, the place where each was reared, the site of his house, the place of his death and burial, and sometimes other data, together with lists of

place names of which it is doubtful whether they name places where the body rested on the way to burial or have some other significance, factual or spiritual. The circumstantial nature of these chants might argue for the actual existence of such chiefs on Hawaiian soil, but Kamakau, who records the chants in his Moolelo Hawaii (1869), tells how, in the time of Kuali‘i of Oahu and later in that of Kamehameha-nui of Maui, the genealogists got together and established the genealogical lines back to Puna and Hema, sons of Aikanaka, from whom Hawaiian chief families count their ancestry; Oahu and Kauai families from Puna, Maui and Hawaii from Hema, traditional settler in New Zealand with the Menehune. At that time the genealogical chant for each chief was probably harmonized with local tradition and crystallized into its present form. The legends have passed into nursery tales and lost the grim character preserved to them in less sophisticated groups, but as a whole they follow closely the pattern common to the whole area where these names appear.

The cycle tells of a woman from a cannibal group who weds a chief in another land and, becoming dissatisfied, returns home, leaving two children, Puna (Punga) and Hema. Hema wins a goddess as a wife, and when his child is to be born he goes away to seek a birth gift and is taken prisoner. His eyes are plucked out and he himself is thrust into the filth pit. His son Kaha‘i (Tawhaki) goes to rescue him and to avenge his wrongs, accompanied by his brother Alihi (Karihi, Kari‘i), who does not share his godlike nature and is hence unable to endure the difficulties of the journey. He is guided by an old blind ancestress who is discovered roasting food and whose eyesight is restored in return for the information sought. Kaha‘i's son Wahieloa is also taken captive, and his son Laka goes to seek his bones, carried across seas in a double canoe fashioned for him by the canoe-building gods and the little spirits of the forest who are his family deities.

(a) Thrum version. Ai-kanaka (Man-eater) is a Maui chief, son of Heleipawa, son of Kapawa. He is born at Kowali-Muo-lea,

at a place called Ho‘olono-ki‘u in Hana district and reared at Makali‘i-hanau, and his home is on Kauiki hill. He is a good industrious man and a kind ruler. Hina-hana-ia-(i)-ka-malama (Hina who worked in the moon), or Hina-mai-ka-lani ( Hina from the heavens), comes from Ulupaupau in Kahiki to be his wife and to them are born, first, imbecile children, then Puna-i-mua (Puna the firstborn), and last Hema. Hina's servants are Kaniamoko and Kahapouli. After the birth of Puna, Hina begins to enlarge her landholdings. The children's excrement has to be carried to the north side of the water hole at Ulaino and Hina wearies of their constant messing and the tapu involved in the disposition of the excrement. Hence on the night of Hoku (Full moon) she leaps to the moon from a place called Wanaikulani. Her husband leaps to catch her, the leg breaks off in his hand (hence she is called Lono-muku), and there she hangs in the moon to this day. 1

(b) Kamakau version. Aikanaka, son of Kailoau, son of Heleipawa, is born in Kipahulu, Hana district, on East Maui. The place of his birth and the site of his house on the hill Kuekahi can still be seen. Strange stories are told of his wife Hina-hanaia-ka-malama or Hina-ai-ka-malama (Hina fed on the moon). She is said to have found food from the moon in the shape of the sweet potato called hualani. Her husband cut off her foot and threw it to the moon where she lived. 2

According to Malo, 3 Aikanaka died at Aneuli, Pu‘uolai, in Honuaula, Maui, and was buried in Iao valley. An early school record makes Hana-ua-lani-ha‘aha‘a the place of Hina's ascent and adds, "If her husband had not cut off her legs she would have reached the locality of the sun." 4 The Moolelo Hawaii (1838) reads: "Because the children made so much excrement she fled away and lived in the moon. As she flew up, her husband cut off her foot, hence she was called Lonomuku. What a grand lie!" 5 Nursery tales today center upon

the weariness caused by the constant running to and fro from Kauiki to Ulaino, a distance of a mile or so, to deposit the children's messes, a situation made amusing by the dramatic way in which the story is told. The theme occurs in traditional Polynesian variants; in Maori it connects with the use of a latrine. A local version collected in Hana in 1932 makes the husband the one who wearies of cleaning the children or does not like being given the child to clean.

He takes large gourds [for which the neighboring district of Hamoa is famous], one under each arm, and leaping from the hill Ka-iwi-o-Pele [where the site of the house can be seen today] floats away to the moon.

[paragraph continues] A similar story is told in Mangaia of the god Tane.

Tane comes from Avaiki and marries a sister of Ina-of-the-moon. She becomes jealous and he weaves himself baskets out of coconut fronds and, using them for wings, flies away to his own land. 6

[paragraph continues] In Rarotonga:

Ngata wins Ngaro-ariki-te-tara, the beautiful daughter of Kuiono, and after recovering her from Avaiki and again from the land Ka-opu-te-ra (of sunset) he abandons her forever because she has left their child with him to tend while she pays a visit to Variiri and the child is fretful. 7

[paragraph continues] In New Zealand:

Hapai-nui-a-maunga (Great lifter of mountains) comes from heaven to wed Tawhaki. A child is born. He complains of its filth. She takes the child, steps off the roof gable and goes back to heaven. 8

Maori. Whaitiri (or Awa-nui-a-rangi) of the heavens is a man-eater. She hears of Kai-tangata on earth and, taking literally a name perhaps signifying victory over enemies, comes

to earth and makes him her husband. When she finds he is not really a man-eater she is disappointed. She bears him children, Punga and Hema (and others). He complains of their filth (or discusses her with others) and she returns to the heavens (having first made a filth pit for the children). Her husband tries to catch her by her garment in some versions. 9

Tahiti. Nona (or Haumea), a cannibal woman of high rank, lives at Mahina (Moon) in North Tahiti. Her husband, a chief of high rank of the house Tahiti-to‘erau abandons her. Her daughter Hina hides her lover in a cave which is opened by a spell. The mother listens to the spell, finds and devours him. The girl flees and is protected by a hairy chief named No‘a (Noahuruhuru) who kills the cannibal mother-in-law, Nona, and marries the girl. Pu‘a-ari‘i-tahi and Hema are their children. 10

Tuamotu (Anaa). Nona is the daughter of Te-ra-hei-manu and the girl Hei-te-rara who is daughter of the ogress Ragi-titi. She desires Noa-makai-tagata and they sleep together. Noa insults Nona by complaining about her bad odor and she leaves him for another lover. Noa follows her, kills the new lover, and brings back Nona to his own land. 11

Rarotonga. Te-meru-rangi is the father, Ina-ma-ngurunguru the mother of Ema, father of Taaki and Karii. Te-meru is also known as Kai-tangata and Tui-kai-vaevae-roroa. 12

The Tuamotu version is related to the story told (at Ra‘iatea) in the Tahitian group of Hiro and his beautiful wife Vai-tu-marie, parents of Marama (Moonlight). Hiro overhears his wife laughing with a neighbor about her husband's strong odor, and puts her to death. Her son Marama discovers and grieves over her death, but nothing comes of the incident. 13

Puna is brought up on Oahu, Hema on Maui at Kauiki, called Hawaii-kua-uli (Hawaii of the green back). Hema grows to be a handsome man and takes Lua(Ulu, Ula)-mahehoa from the upper Iao valley in Wailuku as his wife. In the fifth month of her pregnancy he sails after the birth gift called Apo-ula (Red feather band) to the land of the child's maternal grandparents. They are deep-sea divers and "it is a custom in that country to take men's eyes for fishbait." Hema's eyes are gouged out and he loses his wits ("caught by the aaia bird of Kane"). The last part of his chant reads, in Emerson's translation:

Maori. Hema is the son of Kai-tangata and Whaitiri. He weds Ara-whita-i-te-rangi (Arahuta) who becomes mother of Tawhaki and Karihi 15 or weds Kare-nuku, who becomes mother of Pupu-mai-nono, Karihi, Tawhaki, 16 or weds Uru-tonga and has Karihi and Tawhaki 17 or Hema, daughter of the same, weds Hu-aro-tu and has Karihi, Pupu-mai-nono, Tawhaki. Forbid-den to follow her mother when Whaitiri leaves for her own country, she attempts the journey and is taken captive by Te-tini-o-Waiwai (The little spirits of the water). 18 Hema is slain by the Ponaturi, underwater people, 19 or killed and his wife taken captive at the settlement of the whale people Paikea, Kewa, and Ihu-puku, 20 or slain by the Patu-pae-a-rehe. In some versions 21 Karihi is called the "child" of Whaitiri.

Tahiti. Hina weds No‘a-huruhuru (hairy), who has saved her from her cannibal mother Rona (or Haumea), and has two sons, Pu‘a-ari‘i-tahi and Hema. The mother favors Hema because he does not refuse to louse her hair and to swallow a red (and a white) louse which he finds in so doing. She accordingly promises him a goddess for a wife. He is to find Hua-uri (or Hina-tahutahu) at her bathing pool called Vai-te-marama (at the Vaipoopoo river at Hanapepe) and catch her by the hair and carry her past four (or twenty) houses without letting her feet touch the ground; then she will lose her power and follow him. The first time he cannot resist her pleadings, lets her down, and she runs away from him; the second time he succeeds. Tafa‘i-iri-ura(-i-o-ura) is their child, Arihi-nui-a-Pu‘a is the child of Pu‘a. When her child is abused by the other children Hema's wife curses her husband and he tries to commit suicide by leaping head down from the A‘a-‘ura and is caught by spirits and carried to the Po (Tumu-i-Havai‘i) where his body becomes "a deposit for the spirits' dung" and his eyes are used "as morning lights at the mat-weaving place of Ta‘aroa's daughter." Hence in Tahiti a man with a skin disease is compared with Hema as "a place for the excrement of the spirits." 22

Compare the Marquesan story of Kena who goes to the underworld after his wife and must carry her out in a basket and by no means let her out or she will escape. The first time he fails; the next time he succeeds. 23 See also the Hawaiian story of "Hiku and Kawelu."

Tuamotu. (a) North islands. Hema is son of Noa-huruhuru and Hina, daughter of the cannibal woman Rona. Hina sends her son to seize Hua-uri, "queen of Niue," and through the powerful incantations of Noa he brings her back "naked and wailing." When their son Tafa‘i is abused by the other boys Hema commits suicide and the "fairies of Matua-uru" catch him and confine him in a latrine. 24

(b) Fagatau. Hema is the husband of Hua-uri, younger sister

of Arimata, and there is jealousy between the sisters over their sons Niu-kura and Tahaki. Hema and Hua-uri go to the sea after a special kind of sea urchin as food for their son. The goblin band of the Matua-uru seize and carry off Hema while Hua-uri escapes. They pluck out his eyes and fasten them to the belt band of the woman Roi-matagotago and use his body as a filth pit. 25

(c) Anaa. Hema lives in the upper valleys and seizes Hua-uri who lives by the sea, daughter of Titimanu and Kuhi, while she is digging arum root in the uplands. Kuhi sends a magic bunch of feathers to find Hua-uri, and the wife, fearing lest her parents kill Hema, returns to her parents and wins their consent to the marriage, although they warn her that the man is not her equal. When her child is to be born she goes to her parents' home and is bidden by her mother pick and eat a louse from the mother's head. She picks first a black and then a red louse and the mother predicts that her second child will be famous. When this second child is to be born, Hema encroaches upon the beach where the goblins of Matua-uru catch crabs and is pursued and seized. 26

Rarotonga. Ema is descended from Te Memeru, high chief of Kuporu. His wife is Ua-uri-raka-moana who dwells by the deep sea. Kari‘i, Taaki, and the girls Puapua-ma-inano and Inanomata-kopikopi are her children. The older son Kari‘i refuses to bite the ulcer on her head; Taaki complies and power enters into him so that light shines from his whole body. Kari‘i is jealous because his father favors Taaki and offers his father Hema in sacrifice at the marae to "many gods." Hema's eyes are taken possession of by Tangaroa-a-ka-puta-ara, his body by the little gods. "Ema, heap of filth!" the gods call him. 27

Samoa (Vaitapu). The brothers Punga (Pu‘a) and Sema seek wives. Punga has many wives, Sema only a woman all sores named Matinitini-ungakoa. He is derided, but his wife dives three times and becomes beautiful, with a red skirt and lightning

flashes. Her children are Tafaki (Tafa‘i) and Kalisilisi (‘Alise).

The Kaha‘i (or Tawhaki) legend follows a more or less regular pattern, although with local variations. Hema is always the father (in one instance, mother); his wife is generally a goddess. A brother Alihi constantly fails in under-takings in which Kaha‘i succeeds because of his godlike endowments or of the chants of which he has command. His cousins by his father's brother Puna (Punga, Pu‘a) or his own older brothers often seek Kaha‘i's life.

Hawaii. Kaha‘i-nui (Kaha‘i the strong) is son of Hema, a chief of East Maui living on the hill Kauiki in Hana district, and of Lua(Ula, Ulu)-mahahoa from Iao valley in Wailuku district. He is born in Iao valley at a place called Ka-halulukahi above Loiloa at Haunaka. His chant tells how he goes "by the path of the rainbow" and guided by cloud signs to seek his father, who has had his eyes. gouged out on an expedition to foreign lands. His brother Alihi accompanies him but is unable to keep the pace. The chant, as translated by Emerson, runs:

[paragraph continues] On his return Kaha‘i lands on the Ka-u coast of Hawaii and weds Hina-ulu-ohia at Kahuku and their child Wahieloa is born at Wailau (or Punalu‘u). Kaha‘i dies at Kailiki‘i in Ka-u (hence

some say he never lived on Kauiki) and is buried in Iao valley, or, as the chant says,

Maori. Tawhaki's relatives are jealous because all women love him and they set upon him and leave him for dead. He restores himself by his own power (or is restored by wife, mother, or sister) and leaves the country (calling down a flood upon those who have attempted his life). He and Karihi his brother go to search for their father's bones (and to release their mother from captivity in some versions). The bones are in the possession of an underwater people called Pona-turi or Patu-pae-a-rehe (or, of people like small birds) who cannot bear the sunlight but come to land and sleep at night in a house called Manawa-tane. Approaching, he hears his father's bones rattle (and finds his mother acting as watchman). He stops up the chinks until it is broad day, and the spirit people are killed by the sunlight (or killed as they attempt to escape from the house). Or Tawhaki follows to the settlement where the father was killed, hears the bones rattle, and avenges the father's death. He ascends to the heavens guided by an old blind ancestress whom the brothers en-counter roasting food and whose eyes he restores. She directs him on his way, but Karihi is unable to make the ascent. She also helps him secure a bird-woman as wife (Maikuku-makaha by name) when she comes to her bathing pool; or a goddess (Tangotango or Hapai) comes down from heaven to be his wife; or he takes the wife of his enemy at the settlement he visits (Hine-nui-i-te-kawa). Sometimes he loses her through a broken tapu or because he hurts her feelings, and ascends to the heavens in search of her. 29

In the Maori, Tawhaki is represented as man or god at discretion. 30 He is god of thunder and lightning. 31 He causes a flood by stamping on the floor of the heavens. 32 At the top of the mountain he takes off his human form and clothes himself with lightning. 33 He learns from his sister Pupu-mai-nono incantations for walking on water without sinking. 34 From Tama-iwaho (Te-maiwaho) he learns incantations to cure diseases. 35 From Maru he learns war chants (such as the Maori still use when cutting off hair to prepare for war), 36 by means of which he climbs to the heavens of Rahua, keeper of the "elements of life."

The same incident may serve to embellish the legend of different members of the family cycle.

(a) Tawhaki disguises himself as an old man and is taken as a slave when he enters the settlement. Left to carry home the axes when the men quit work, he completes with a few strokes the canoe which the men are shaping, and brings in a huge load of wood besides. He goes to sit in a tapu place, unrecognized by his wife. The next day he appears in splendid person with lightning flashing from his armpits, claims his wife, and performs the proper ceremonies for his little daughter. 37

(b) Tawhaki's descendant, Rata's son Tu-whaka-raro, has been killed by the Poporo-kewa people and his wife Apakura summons her son Whaketau to avenge her. He mingles with the wood gatherers, hears his father's bones rattle, and when recognized by those in the house, escapes through the smoke-hole and sets fire to the house Tihi-o-manono. 38 He asks a slave by which road Poporo-kewa comes, makes a slave summon him for the sweet-potato planting, lays a noose and catches him (as in the Rata story). 39

The legend of Tafa‘i in Tahiti belongs to the chief (ari‘i) culture. 40

[paragraph continues] Tahiti. Tafa‘i's mother is a goddess from another world named Hina-tahutahu or Hua-uri (Ouri). His older cousin is Arihi (Arii)-nui-a-Pu‘a. Anuenue (rainbow) is the canoe in which he sails. He is blond and handsome. He lives in the Tapahi hills of Mahina district, north Tahiti. His footsteps are to be seen in the hard rock.

The children of Pu‘a kill (or beat) him because he excels them in sports, but he is brought back to life (by his mother) and later avenges himself upon the boys by turning them into porpoises of the sea. He descends to Po with Karihi (Arihi-nui-a-Pu‘a) after his father and, helped by his old blind ancestress and guided by the dawn-star maiden, finds him kept in the spirits' filth pit (the Matua-uru) and his eyes being used "for morning lights at the net-plaiting place of Ta‘aroa's daughters." He burns down the house with all inside, after netting the place to prevent escape, and secures the eyes from the girls.

Pu‘a's children go on a courting expedition to Nu‘u-ta-farata (some say to Hawaii) to woo a dangerous chiefess named Te-ura-i-te-ra‘i (Redness in the heavens), or Tere, and refuse to let him go with them. He makes a canoe out of a coconut sheath, reaches land first, and after his brothers have been killed in the tests proposed, namely, to pull and prepare awa from the living awa plant (Tumu-tahi) and to slay for the feast the boar Mooiri (Moiri) who swallows men whole, he succeeds, eats the whole feast lest the creature come to life, restores his brothers to life, then deserts the chiefess. On the way home he turns his brothers into porpoises.

Tafa‘i weds Hina of North Tahiti, famous for her long black hair. She dies and he pursues her spirit to Te-mehani, the last place on the island whence spirits take their departure to paradise or down to Po, and restores her spirit to her body. They live at Uporu in Mahina district of North Tahiti and Wahieroa is their son. 41

For the episode of the awa root and boar-killing test see the Tahitian story of Hiro, who digs up the tree called Ava-tupu-tahi (Ava standing alone) and kills the boar Mo‘iri

and the keepers of the two, Taru-i-hau and Te-rima-‘aere 42 and compare the Mangaian version of Ono-kura, who fells the ironwood tree which has formerly restored itself and slain the feller, and kills the demon Vaotere at its taproot. 43 Other episodes of the Tafa‘i story are drawn from familiar Polynesian themes. In one version Tafa‘i's ancestral shark Tere-mahia-ma-Hiva (Nutaravaivaria) carries him over the ocean but swallows his brother. Tafa‘i redeems his brother with a big load of coconuts, but later cracks a coconut on the shark's head and the shark deposits both brothers in the sea, 44 an episode also found in the Siouan Indian twin story and hence probably borrowed.

Tuamotu. Tahaki is son of Hema and Hua-uri; Niu-kura is son of Hua-uri's older sister Arimata. Both mothers vaunt the deeds of their sons. Niu-kura is jealous and sends Tahaki to dive, kills him with a spear, and cuts his body to pieces. His foster brother Karihi saves the phallus and testicles and the mother restores him to life. When Niu-kura and the other brothers go voyaging (or swimming) the mother (or Tahaki) invokes her gods and they are changed into porpoises (or whales) and live in the sea.

Tahaki and Karihi (Ariki) go to the land of Matua-uru(-au-huru), directed by old blind Kuhi (Uhi) who gives them a net to trap the spirits and offers to each of them one of her star maidens who come to her house at night. Karihi fails to catch one, but Tahaki catches the star called Tokurua-of-the-dawn; they struggle "way up to the floor of the upper heaven and down again to earth" but he holds on to her and she follows and lives with him. (He goes to a relative named Titi-manu and is sent to the house Maurua-of-the-region-of-the-gods "toward the flaming rays of the dawn" to woo Hora-hora and they have a daughter Mehau.) They find Hema in the filth pit, clean him up with coconut oil, restore his eyeballs (fastened to the belt of the woman Roi-matagotago), and kill the spirits (but save the woman).

Tahaki climbs the High-coconut-to-Hiti (Niu-roa-i-Hiti) ("goes to Niue," says Leverd) and is blown off naked into Hina's bathing pool. Since the "long girdle of Hiva" fits him exactly, he is recognized as the "grandchild" of Ituragi and Tuaraki-i-te-po and sent to woo the high chiefess Hapai. She at first rejects him, but finally recognizes his red body, perfumes herself, and gives herself to him (or recognizes him too late and he abandons her). Tane has not been consulted. He sets tests: to pass before his face, sit upon his three-legged stool, and pull up his sacred tree by the roots. From the hole thus made Tahaki can look down to Havaiki. For a long time the two are happy together, then he makes love to her sister Teharue. Hapai is jealous. He leaves her and she follows and laments his death at Fagatau. 45

Rarotonga. Taaki is the son of Ema and Ua-uri-raka-moana. Ariki is his elder brother. Ariki is jealous of Taaki's superior accomplishments.

The mother predicts excellence for Taaki and Ariki has his father offered in sacrifice and tries to kill his brother. Taaki destroys three companies of fifty men sent to bring him to the bathing pool where Ariki plans to kill him, but follows his sister Ianao-mata-kopikopi and is cut to bits. His sister Puapua-ma-inano brings the pieces together and restores him to life.

Taaki sets out to seek his father by the road between heaven and earth called Nu-roa-ki-Iti. He passes two women beating tapa, climbs to the breast of his mother's sister Vaine-nui-tau-rangi (Altar of Tane), and goes to Tangaroa-aka-puta-ara after Ema's eyes and to the "house of many gods" after Ema's body, which is just about to be burned in sacrifice, and kills the "many gods."

At Rangi-tuna he finds Tu-tavake who gives him culture gifts, among them Maikuku. 46

Moriori. Tawhaki is the son of Hema and father of Wahieroi by his wife Hapai. She is the daughter of Tu and Hapai-mao-mao. Since he will not allow her to give birth in the house Hapai leaves him and goes back to heaven. He goes thither on the path of the spider web to seek her. He gives sight to the old blind woman Ta Ruahine-mata-moai. He uses chants to insure calm winds. 47

Samoa. Tafa‘i belongs to a race of giants. He can hurl a coconut tree and once "plucked up by the roots a great Malili tree, eighty feet high" and "carried it off on his shoulder, branches and all." He can leave his footprint in the solid rock as if it were sand. 48

Tafa‘i's parents Pua and Singano (Sigano) have names of sweet-smelling trees. Sina-taeoilangi, a woman of the heavens, daughter of Tangaloa-lagi, is sought in marriage by Tafa‘i. His messenger goes on the road to heaven and carries a present of musty food. This is rejected but Tafa‘i's suit is accepted. The two brothers disguise themselves as if they were ugly lest they be slain by the people of the heavens, and she refuses to have anything to do with them. In the morning they make their bodies handsome and too late she sees the light flashing from them. They leave her and she follows. They abandon her trapped in a chasm, but Pua and Singano come and release her and take her to live with them in the uplands of earth. She goes to the sea after sea water for cooking in the hope of meeting Tafa‘i. He sees and desires her, but she returns to the uplands and, mounting upon the housetop, takes her way toward heaven, bidding him follow. On the way she meets her father and his tribe bringing her marriage gifts and they persuade her to return to Tafa‘i, where his sister turns herself into an ifiifi tree and shakes down abundance of food for the feast. From this union is born La (Sun), the heat of whose body is "like a whirlwind." La goes to live with his mother in the skies and the story of his adventures in far lands follows. Tafa‘i takes Sina-piripiri and has Fafieloa (Wahieloa). Fafieloa takes Tula and has Lata (Laka). 49

The Kaha‘i cycle may be analyzed as follows:

(A) Ill-usage by relatives, (A1) avenged by their destruction.

(B) Expedition to a far land to rescue father (B1) from a filth pit into which he has been thrown, (B2) to restore his eyes (B3) and avenge his wrongs.

(C) Ascent to heaven (C1) guided by an old blind relative cooking food (C2) whose eyesight he restores (C3) and who gives him directions (C4) to find a wife.

(D) Winning of a wife (D1) whom he deserts (D2) or she deserts him (D3) and he goes to bring her back.

The two adventures therefore most commonly told of Kaha‘i in Polynesian legend are the quest in search of his father Hema and a courting expedition, which may take the form of a search for a lost wife. The restoration to sight of an old blind ancestress roasting food, who directs his search and helps him to a wife from among her daughters, is a common episode in the story.

In Maori versions she is the blind ancestress Whaitiri, Mata-kere-po (Blind eyes), Te-ru-wahine-mata-moari, or Te-pu-o-toi, and she is found roasting ten taro, sweet potatoes, bananas, or other vegetables. He takes away one at a time until she is aware of his presence, then makes his relationship known, cures her blindness with a touch or a slap, with clay and spittle, incantations, or his brother's eyes and she shows him the spirit path to the heaven of his ancestors, in the shape of an arati‘ati‘a (notched ladder), hanging roots, a wall, spider's web, kite line, or rope fastened to her neck. In several variants the capture of Maikuku-makaha (her daughter) follows and the ascent to the heavens is made in pursuit of this wife. 50 Among the Moriori, the old blind woman to whom Tawhaki gives sight is Ta Ruahine-mata-moai and he ascends to the heavens by the path of the spider web. 51 In Tahiti, Ari‘i and Tafa‘i on their way to seek Ema find Kui (Uhi) the blind in Havai‘i, steal her taro, avoid her

fishhook called Puru-i-te-maumau and her line "Shark of the firmament" 52 and kill her; 53 in Tumu-i-Havai‘i they meet blind Ui, from whose four star daughters, named after the red feathers of the kula bird, Tafa‘i selects a wife, the morning star Ura-i-ti‘a-hotu, to direct him on the way. 54 In the Tuamotus, Tahaki and Karihi find Kuhi (or ‘Ui) and Tahaki restores her sight by throwing coconuts at her eyes (from a tree named Te-niu-roa-i-Hiti) and wins the dawn star for wife. 55 In Rarotonga the place of the blind ancestress is taken by Vaine-nui-tau-rangi. Taaki climbs up to her breasts and gains recognition from her as descendant. In a Tane story, Tane, on the way to Iti-kau, goes first to Iti-marama, where he cures old blind Kui with a coconut plucked from a tree guarded by insects. 56 So in Mangaia, Tane swings over to Enua-kura (Land of red parrot feathers) on a stretching tree and restores the sight of old blind Kui and marries one of her daughters named Ina, whom he later deserts because she becomes jealous. 57 In Manihiki, Maui follows his parents to the underworld, restores the sight of Ina the blind, and obtains from her knowledge of coconuts and taro. 58 In a Samoan story told in Tokelau, Kalokalo-o-ke-La makes himself known to his old blind grandmother counting eight taro buds, restores her sight, and climbs a tree guarded by insects at whose summit he finds a spinning house and is given a shell to use as a lucky fish lure. 59 In Niue a divine child is cast out at birth, but survives and goes to seek his father. He finds an old woman cooking eight yams, whose sight he restores, and she tells him how to recognize his father. 60 In the Marquesas, the story of "Koomahu and his sister by the blind Tapa" tells how Koomahu climbs to heaven on Peva's beard after his sister, who has been caught on Tapa's hook. He finds old Tapa cooking bananas, restores her

sight, and secures one of her star daughters as guide on the way to find his sister. He finally climbs down from heaven with his sister on the tree which he has planted below on the earth. 61

Although this adventure with the old blind ancestress is not mentioned in the Hawaiian chant of Kaha‘i, the episode occurs in several other quest stories from this group. According to Westervelt, Maui, on his way to snare the sun, is directed by his mother Hina to his old blind grandmother who is roasting bananas for the sun at a place up Kaupo valley where there is a large wiliwili tree. The old woman gives him another snaring rope and an axe, and hides him by the tree until the sun appears. 62 In the Kana legend, Uli sends her grandson Kana to bring back the sun. That she is conceived as blind is shown by the statement that she has a rope stretched from her door to the sea to guide her steps. Niheu is killed in the ascent but restored by his brother on Kana's return victorious. 63 In the legend of Kila, Moikeha's son on his way to Kahiki visits the rat-woman Kane-pohihi (Kuponihi), whom he finds blind and counting her cooked bananas. 64 Aukelenui-a-iku, on his way in search of the water of life, finds at the bottom of the pit Old-woman-Kaikapu roasting bananas, steals them one by one, and restores her sight with two sprouts of coconut, in return for which and her recognition of him as a grandchild, she directs him how to win the water of life. 65

The episode, in Kaha‘i's quest after his father, of the destruction of the spirits who fear daylight by trapping them inside a house is referred by Von den Steinen to stories of expeditions from the Marquesas islands undertaken after the red (kula, kura, ula) parrot feathers, so highly prized for ornament, upon one of which trips Hema is supposed to have lost his life. The Marquesan journey to Aotona after bird feathers is to the Cook group thirteen hundred miles to the southwest from the Marquesas. The story is here connected

with Aka or Aka-ui (Laka), grandson of Tafa‘i, who goes after the feathers to adorn his son and daughter when they arrive at puberty.

Aka's party get directions from Mahaitivi who lives at Poito-pa in the neighborhood of Atuona on Hivaoa and has visited Aotona and become a friend of the Kula bird, and his sons Utunui and Pepu conduct the party. They set out from the north coast of Hivaoa with a double canoe named Va‘a-hiva carrying 140 rowers, eighty to a hundred of whom die of hunger before they reach Aotona. Each of the islands at which they touch is famous for certain scented plants, fruits, or bird feathers whose names are mentioned, and the travelers are given free way when their own names are spoken. At Aotona they build a house or rebuild Mahaitivi's, sprinkle roasted coconut as a lure, and hide until the "kula" have filled the house, thinking that their friend has returned. When all are inside they close the doors and fill 140 bags with feathers, that the families of the dead may also receive their portion. 66

[paragraph continues] The theme appears in Maori story unconnected with the Kaha‘i cycle:

Tangaroa steals the child of Ruapupuke and sets him up as a figure at the end of the ridgepole of a house at the bottom of the sea where live the underwater people who fear daylight. The father follows and, advised by an old woman, stops up the chinks of the house until it is broad day and then lets the sun-light kill those within. 67

242:1 Thrum, More Tales, 69-71.

242:2 Ke Au Okoa, October 21, 1869.

242:3 323.

242:4 For. Col. 5: 658.

242:5 41.

243:6 Gill, 107-114.

243:7 JPS 27: 185.

243:8 Taylor, 143; White 1: 115; Grey, 36.

244:9 White 1: 87-89, 95-97, 119-121, 125, 126-128; JPS 19: 143; Taylor, 138-143; Wohlers, 15-16.

244:10 Henry, 552-555.

244:11 Stimson, Bul. 148: 60.

244:12 Savage, JPS 19: 142-144; Smith, JPS 30: 1.

244:13 Henry, 543-545.

245:14 Thrum, More Tales, 70-72; Kamakau, Ke Au Okoa, October 28, 1869; Malo, 323; For. Col. 6: 319; Moolelo Hawaii (1838), 41; Thrum, JPS 31: 105-106.

245:15 White 1:88, 89, 128; JPS 37: 360.

245:16 White 1: 121; Wohlers, 17.

245:17 Grey, 36.

245:18 White 1: 54-55.

245:19 Grey, 37; JPS 7: 40.

245:20 Wohlers, 17; White 1: 121.

245:21 Ibid. 95-97, 125.

246:22 Leverd, JPS 21: 5-7; Henry, 555-561; Ahnne 49: 264-266.

246:23 Handy, Bul. 69: 120.

246:24 Leverd, JPS 20: 173-175.

247:25 Stimson, Bul. 127: 50.

247:26 Ibid. 148: 60-68.

247:27 Smith, JPS 30: 1-2, 5; Savage, JPS 19: 143.

249:28 Kamakau, Ke Au Okoa, October 28, 1869; Malo, 323; For. Pol. Race 2: 16-18; Thrum, JPS 31: 106.

249:29 Grey, 36-48; Henare Potae, JPS 37: 360-366; Taylor, 138-147; Wohlers, 17-20; White 1:55-57, 57-58, 59, 61-67, 89-90, 97-108, 110-111, 111-113, 113-114, 115-118, 121-125; Hare Hongi, JPS 7: 40-41.

250:30 White 1: 60.

250:31 Ibid., 59.

250:32 Ibid., 55.

250:33 Ibid., 55.

250:34 Ibid., 61-62.

250:35 Ibid., 125-126.

250:36 Ibid., 103-108, 111, 129-130.

250:37 Grey, 44-48.

250:38 White 2: 147-154.

250:39 See note 29, chapter xviii.

250:40 Handy, Bul. 79: 16.

251:41 Henry, 552-565 and discussion 565-576; Leverd, JPS 21: 3-25; Gill, 250-255; Ahnne 52: 406-408.

252:42 Henry, 537-539.

252:43 Gill, 81-85; cited by Henry, 532-535.

252:44 Gill, 253-254.

253:45 Stimson (Fagatau), Bul. 127: 50-77 (given by a chief of mixed Fagatau and Rekareka ancestry); (Anaa), Bul. 148: 73-89, 91-96; Leverd, JPS 20: 175-184.

253:46 Percy Smith, JPS 30: 1-13; 19: 143.

254:47 Shand, JPS 7: 73-80.

254:48 Turner, 136-137.

254:49 Pratt (from Wilson, 1835), 448-451, 455-458; Krämer 1: 456-457.

254:50 White 1: 56-57, 58, 62-63, 89-90, 100-101, 112, 116-117, 121-123, 128-129; Henare Potae, JPS 37: 361; Grey, 42-43; Wohlers, 17-18.

254:51 Shand, JPS 7: 73.

256:52 Ahnne.

256:53 Gill, 251-253.

256:54 Leverd, JPS 21: 9-11.

256:55 Stimson, Bul. 127: 62-66; Leverd, JPS 20: 176-177.

256:56 Smith, JPS 30: 206-208.

256:57 Gill, 109-111.

256:58 Ibid., 65-66.

256:59 W. Burrows, JPS 32: 168-170.

256:60 JPS 12: 92-95.

257:61 Von den Steinen, ZE 1933, 370-373.

257:62 Maui, 44-46.

257:63 Rice, 103.

257:64 Thrum, More Tales, 24-26; For. Col. 4: 162.

257:65 Ibid. 92, 94.

258:66 Von den Steinen, ZE 1933, 9-21.

258:67 White 2: 162-163.