Stonehenge and Other British Stone Monuments Astronomically Considered, by Norman Lockyer, [1906], at sacred-texts.com

THE foregoing chapters will have shown that in dealing with the ancient monuments from an astronomical point of view, we have to consider chiefly the direction of the sight-lines, whether they are marked as in Brittany by long rows of stones—alignments; as at Stonehenge by an avenue; as in some of our British circles, by two or more circles the direction being indicated from the central stone of one to the central stone of the other, or finally by a single standing stone or barrow.

It is important then that before we proceed further in our inquiries we should consider how a meaning is got out of these directions, and I propose to devote this chapter to this question, so that the full use of the "azimuths" already referred to and others which are to follow may be fully understood.

There is another matter, at which I hinted on pp. 36 and 42. We have to inquire whether there are any stones or barrows marking the direction of the rising or setting of stars, as well as those which deal with the rising and setting of the sun at different times of the year, which we have already found at Stonehenge and in Brittany. To face this question we have to consider the stellar as well as

solar conditions of observations, and as the former are the simpler I will begin with them, especially as now there is no question whatever that the rising and setting of stars were provided for.

In continuation of my work in Egypt in 1891, and Mr. Penrose's in Greece in 1892, I have recently endeavoured to see whether there are any traces in Britain of star observations, including those connected with the worship of the sun at certain times of the year. We both discovered that stars, far out of the sun's course, especially in Egypt, were observed in the dawn as heralds of sunrise—"warning-stars"—so that the priests might have time to prepare the sunrise sacrifice. To do this properly the star should rise while the sun is still about 10° below the horizon. There is also reason to believe that stars rising not far from the north point were also used as clock-stars to enable the time to be estimated during the night in the same way as the time during the day could be estimated by the position of the sun.

I stated (Dawn of Astronomy, p. 319) that Spica was the star the heliacal rising of which heralded the sun on .May-day 3200 B.C. in the temple of Menu at Thebes. Sirius was associated with the summer solstice at about the same time.

Mr. Penrose found this May-day worship continued at Athens on foundations built in 1495 B.C. and 2020 B.C., on which the Hecatompedon and older Erechtheum respectively were subsequently built, the warning star being now no longer Spica, but the cluster of the Pleiades rising, or Antares setting, in the dawn.

It is generally known that Stonehenge is associated with the solstitial year, and I have suggested that it was

originally connected with the May year; but the probable date of its re-dedication, 1680 B.C., was determined by Mr. Penrose and myself by the change of obliquity.

Now if Stonehenge or any other British stone circle could be proved to have used observations of warning stars, the determination of the date when such observations were made would be enormously facilitated. Mr. Penrose and myself were content to think that our date might be within 200 years of the truth, whereas if we could use the rapid movement of stars in declination brought about by the precession of the equinoxes, instead of the slow change of the sun's declination brought about by the change of the value of the obliquity, a possible error of 200 years would be reduced to one of 10 years.

In spite of this enormous advantage, no one so far as I know has yet made any inquiry to connect star observations with any of the British circles.

I have recently obtained clear evidence that some circles in different parts of Britain were used for night work and also in relation to the May year, which we know was general over the whole of Europe in early times, and which still determines the quarter-days in Scotland.

If the Egyptian and Greek practice were continued here, we should expect then to find some indications of the star observations utilised at the temple of Min and at the Hecatompedon for the beginning, or the other chief months, of the May year.

I have found them, and I will now show the method employed.

To begin with, if we assume that the astronomer-priests

here did attempt such observations, what is the most likely way in which they would have gone to work?

The easiest way for the astronomer-priests to conduct such observations in a stone circle would be to erect a stone or barrow indicating the direction of the place on the horizon at which the star would rise as seen from the centre of the circle. If the dawn the star was to herald occurred in the summer, the stone or barrow itself might be visible if not too far away, but there was a reason why they should not be too close; in a solemn ceremonial the less seen of the machinery the better.

Doubtless such stones and barrows would be rendered obvious in the dark by a light placed on or near them. Cups which could hold oil or grease are known in connection with such stones, and a light thus fed would suffice in the open if there were no wind; but in windy weather a cromlech or some similar shelter must have been provided for it.

Now if these standing stones or barrows were ever erected and still remain, accurate plans—not the slovenly plans with which Ferguson and too many others have provided us, giving us either no indication of the north or any other point, or else a rough compass bearing without taking the trouble to state the variation at the time and place—will help us.

I have already pointed out that much time has been lost in the investigation of our stone circles, for the reason that in many cases the exact relations of the monuments to the chief points of the horizon, and therefore to the place of sunrise at different times of the year, have not been considered; and when they were, the observations

were made only with reference to the magnetic north, which is different at different places, and besides is always varying; few indeed have tried to get at the real astronomical conditions of the problem. The first, I think, was Mr. Jonathan Otley, who in 1849 showed the "orientation" of the Keswick circle "according to the solar meridian," giving true solar bearings throughout the year.

In my opinion the most accurate plans conceivable, in the absence of a long and minute local inquiry, are the 25-inch maps of the Ordnance Survey, on which, I have it on the authority of Colonel Johnston the distinguished Director, each stone may be taken to be shown with a limit of error of 6 feet. With a large circular protractor azimuths can be read to one minute of arc, and in critical cases the true azimuth of the side lines, which are not necessarily meridians as latitudes are not marked, can be found on inquiry at the Ordnance Office, Southampton.

Having then true azimuths, the next question concerns. the declinations of the stars which may have been observed.

The work of Stockwell in America, Danckworth in Germany, 1 and Dr. W. J. S. Lockyer in England, has provided us with tables of the changing declinations of stars throughout past time, or enough of it for our purpose.

An accurate determination on the 25-inch map of either the azimuth (angular distance from the N. or S. points) or amplitude (angular distance from the E. or W. points).

of the stone or barrow as seen from the centre of the stone circle will enable us to determine the declination of the star at the time when it was observed.

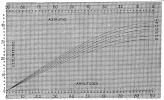

I give a diagram which enables this determination to be made with the greatest ease for any monuments between Land's End and John o’ Groats, whether the direction is recorded by amplitude or azimuth; the declination is read at the side from the value of either indicated, say, by a dot, at the proper latitude.

This, of course, only gives us a first approximation. The angular height of the point on the horizon to which the alignment or sight-line is directed by the stone or barrow from the centre of the circle must be most accurately determined, otherwise the declinations may be one or two degrees out.

In the absence of measurements it is convenient to assume, in the first instance, that the horizon is half a degree high, as with this elevation refraction is compensated, as the following table will show:

In the absence of theodolite observations the actual elevation of the horizon can be roughly found by a study of the contour lines on the 1-inch map. The following heights will agree with the previous assumption of hills ½° high:

|

Distance |

1 |

mile |

|

Height |

= |

46 |

feet |

|

„ |

2 |

miles |

|

„ |

= |

92 |

„ |

|

„ |

4 |

„ |

|

„ |

= |

184 |

„ |

|

„ |

8 |

„ |

|

„ |

= |

368 |

„ |

|

„ |

10 |

„ |

|

„ |

= |

460 |

„ |

Click to enlarge

FIG. 33.—Diagram from finding declination from given amplitudes of azimuth in British latitudes

I also give other diagrams showing the changing declinations of the brightest stars, those which would naturally, be observed, between the years 150 A.D. and 2150 B.C. These have been plotted from the calculations of the authorities I have named.

Fig. 34 deals with the Northern stars. The stars are numbered as follows:—

|

Number. |

Name of star. |

Number. |

Name of star. |

|

1 |

β Ursae Minoris. |

14 |

α Coronae. |

|

2 |

α Ursae Minoris (Polaris). |

15 |

α Geminorum (Castor). |

|

3 |

α Draconis. |

16 |

β Geminorum (Pollux). |

|

4 |

α Ursae Majoris (Dubhe). |

17 |

α Boötes (Arcturus). |

|

5 |

γ Ursae Majoris. |

18 |

β Leonis. |

|

6 |

η Ursae Majoris (Benetnasch). |

19 |

α Leonis (Regulus). |

|

7 |

γ Draconis. |

20 |

α Andromedae. |

|

8 |

β Cassiopeiae. |

21 |

η Tauri (Alcyone). |

|

9 |

α Cassiopeiae. |

22 |

α Tauri (Aldebaran). |

|

10 |

α Persei. |

23 |

α Canis Minoris (Procyon). |

|

11 |

α Aurigae (Capella). |

24 |

α Aquilae. |

|

12 |

α Cygni. |

25 |

α Orionis (Betelgeuse). |

|

13 |

α Lyrae (Vega). |

26 |

α Virginia (Spica). |

On Fig. 35, dealing with the Southern stars, the names are given along the curves.

Now supposing that we have our plans; that we have determined the azimuth of the sight lines; and have found the declination of the star observed; we may find more than one star occupying that declination at various dates.

Which of these stars, then, must we consider?

Obviously those most conveniently situated for enabling the time to be estimated during the night, or those which could have been used as warning stars.

The warning stars can be conveniently picked up by using a precessional globe. From it we gather that about 1900, 1400 and 800 B.C. they were as follows for the critical

Click to enlarge

FIG. 34.—Declinations of Northern Stars from 250 A.D. to 2150 B.C.

Click to enlarge

FIG. 35.—Declinations of Southern Stars from 250 A.D. to 2150 B.C.

α Ceti, α Aquarii, β Orionis, α Capricorni, α Canis Majoris, α Scorpii, α Columbæ, α Pisces Austr., η Argos, α Centauri, α Argûs, α Crucis, α Gruis, and α Eridani.

times of the May year, i.e. May, August, November, February:—

For the solstices, that is, June and, December, the following stars might be used as warners:—

It is obvious that a star used all the year round for night work will warn the sunrise at some one of the yearly festivals.

When the stars having the same declinations are considered from this point of view, the star actually used, and therefore the date of its use, may generally be gathered. I shall show subsequently that some of the stars in the above lists were actually observed in British as well as in Grecian temples.

111:1 Dr. O. Danckworth, Vierteljahrschrift der Astronomischen Gesellschaft, 16 Jahrgang 1881, p. 9. Dr: Stockwell's results have been communicated to me by letter. Some, but not all, of Dr. Lockyer's calculations appeared in The Dawn of Astronomy.