Click to enlarge

Leaning heavily against Little John's sobbing breast, Robin Hood flew his last arrow out through the window, far away into the trees

In all sincerity there should be no more of this tale, seeing that we have found ourselves at last come from beginning to end of Robin's quarrelings with the Sheriff. Most histories end, and end properly, with just such a marriage as we have seen.

Yet, to tell the truth, however strange and distressful, is the business of a good historian; and so it must be written that in the end of it sad days came again for Robin Hood. For five years he lived in peace and prosperity, a faithful, loyal subject, having two sons born to him in his home in Broadweald. Then came the plague, raging and furious, and claimed amongst many victims Marian Countess of Huntingdon.

For a time Robin was as one distraught. He had no joy left to him. He was as one without energy or hope; a miser robbed of his gold, suddenly and cruelly. He gave his two boys into the charge of Geoffrey of Nottingham, and went on a journey to London, there to beg of the King that he might find him active employment, instead of being but one of a guard of honor, as he and his men had so truly become.

Richard had already gone to France, and John was acting as Regent of England in his absence. "Go, shoot some more of my brother's deer," sneered the Prince, having heard Robin impatiently. "Doubtless if you do but slay enough of them he will make you Privy Councillor at the least when he returns."

This great insult fired Robin's blood; he had been in a strange distemper ever since the fatal day of his beloved's death. He answered

the disdainful Prince scornfully; and John, growing white with anger, bade his guards to seize upon him.

Faithful Stuteley helped his master to win freedom from the prison into which he had been flung; and, with the majority of his men, Robin returned to the greenwood life. The King's guard was broken up, for the King had no need of it, nor never would again.

Legends are told of Robin's scornful defiance of the laws, but they are intangible and unauthentic. It is a sure thing, howbeit, that he did not revert to Sherwood and Barnesdale, as some aver, but rather took up his quarters near Haddon Hall, in Derbyshire. There is a curious pile of stones and rocks shown to this day as the ruins of Robin's Castle, where the bold outlaw is believed to have lived and defied his enemies for a year at least. Two stones stand higher than the others. These are supposed to be the seats in the hall of this vanished stronghold whereon Robin and Little John sat delivering judgment on matters of forest law.

Another chronicle gives these stones as being the scene of a wondrous leap done by Robin, to show his men that strength and will were his yet. "Robin Hood's stride," folks say.

One thing is sure--that Prince John did not easily forgive or forget him. After many attempts made upon them at Haddon--some desperate enough, in all conscience--Robin and his men were allowed to be at peace. In one of these encounters Robin was sorely wounded; and none but Little John knew of it.

The wound was in Robin's breast, and looked but a small place. It bled little, yet would not heal; and slowly became inflamed in wider circles. Inwardly it burned him as with a consuming fire, his strength was sapped out from him and his eyes began to lose their shrewdness. No longer could he split an arrow at forty paces, as in olden days.

At last he took Little John on one side. "Dear heart," said he, "I do not feel able to shoot another arrow, and soon the rest will know I am stricken sore. I have it in me to return to London and there give myself to the Prince. Mayhap if I did this he would give you all amnesty here."

"Sooner would I see you dead than you should do such a thing," cried Little John; "I swear it by my soul and by my body! Now listen, dear Master, and I will tell you that I have heard of a wondrous cure for thee. An old beggar came this morn through the woods, and, strangely,

when he spied me, asked if there was not one amongst us ill and hopeless."

"This beggar--where is he?"

"He waits below," said Little John, hurriedly. "I bethought me to talk with Stuteley on the matter. The beggar told me that the Abbess of Kirklees had stayed him as he was traveling past her Priory: 'Go to Haddon, Brother, and there you will find Robin Hood sick unto death. Say that in the woods nearby there is one who is practising magic upon him, having made a little image of Robin Hood. At each change of the moon this rascal doth stick a needle into the waxen heart of this image, and so doth Robin slowly die. Tell him that the name of the man is Simeon Carfax.'"

"Ay, by my soul, but I thought as much. What villainy! What foul villainy! Get me a horse, John, and one each for thyself and Stuteley."

The beggar had gone when they went to the hall. None had offered to stay him. "Let us go quietly, swiftly," said Robin, "for I feel that my hours are short."

They rode all through the day and night, and came upon the Priory in early dawn--a quaint, strange building, surrounded by heavy trees.

The journey and fierce excitement told upon Robin. His wound was beating red-hot irons into his heart; hardly could they get him from his horse to the gate of Kirklees.

Stuteley rang the bell loudly, and anon the door was opened by a woman shrouded in black. She spoke in a cold low voice. "Is this Robin Earl of Huntingdon?" asked she. "I pray God that it may be true, for at this moment the wizard is meditating his very death."

"Tell us where this miscreant doth make his sorcery, good mother," cried Stuteley, and Little John together, "and not all the magic in the world shall save him from our swords!"

"Go out yonder to the left, where ye will find a little stream; nearby it is a tree blasted by Heaven's fires. Under the tree is the man Carfax 1--I have watched and known him for many days. Go quickly, and I will tend your master. See, already he swoons-the hour is very nigh!"

The two men gave Robin into her keeping, with a fury of impatience; then, with brandished swords, ran swiftly in search of the wizard. Robin had swooned, and lay a dead weight in the arms of the Prioress.

With amazing strength and tenderness she lifted his slight body and bore it to a little room, near to the entrance of the Priory. She laid the unconscious man upon a couch, then hastily bared his right arm.

She paused an instant to throw back her hood; then taking the scissors of her chatelaine, suddenly and resolutely gashed the great artery in his arm. He gave a cry of pain and started up. "Be still, be still," she muttered, soothing him. "The pain is naught, it will cure thee--lie back and sleep--sleep."

"Who are you?" he asked, feebly, and with swimming eyes. Then blackness came upon him again, and he fell back upon the couch. Out of the night of pain the cold face of the demoiselle Marie smiled mockingly at him!

She raised herself and softly withdrew. As she locked the door upon him she smiled thinly, wickedly. "So, Robin--at last, Robin," she murmured, "I am avenged."

Two hours later Little John returned. Behind him was Stuteley, anxious and ashamed. They had found a man in the woods, and had killed him instantly, in their blind rage, only to discover then that he was but a yeoman, and not him whom they sought.

"I did hear my master's horn, mother," cried Little John, when the Prioress had opened the wicket to them. "Three blasts it gave."

"'Twas the wind in the trees," said she, serenely. "He sleeps." She prepared to close the wicket quietly. "Disturb him not."

But Little John was alarmed and began to fear a trap. With his sword he hewed and hacked at the stout oak door, whilst Stuteley sought to prise it open.

When it yielded they rushed in upon a sorry scene. Robin lay by the window in a pool of blood, his face very white.

"A boon, a boon!" cried Little John, with the tears streaming from his eyes. "Let me slay this wretch and burn her body in the ruins of this place."

His master answered him with a voice from the grave: "'Twas always my part never to hurt a woman, John. I will not let you do so

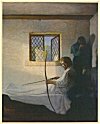

Click to enlarge

Leaning heavily against Little John's sobbing breast, Robin Hood flew his last arrow out through the window, far away into the trees

now. Look to my wishes, both of you. Marian's grave--it is to be kept well and honorably. And my two sons--but Geoffrey will care for them. For me, dear hearts, bury me nearby, in some quiet grave. I could not bear another journey."

They sought to lift him up. "Give me my bow," said Robin, suddenly, "and a good true shaft." He took them from Stuteley's shaking hands, and, leaning heavily against Little John's sobbing breast, Robin Hood flew his last arrow out through the window, far away into the deep green of the trees.

A swift remembrance lit up the dying man's face. "Ah, well," he cried, "Will o' th' Green--you knew! Marian, my heart . . . and that day when first we met, beside the fallen deer! And she is gone, and my last arrow is flown. . . . It is the end, Will--" He fell back into Little John's arms. "Bury me, gossips," he murmured, faintly, "where my arrow hath fallen. There lay a green sod under my head and another beneath my feet, and let my bow be at my side."

His voice became presently silent, as though something had snapped within him. His head dropped gently upon Little John's shoulder.

"He sleeps," whispered Stuteley, again and again, trying to make himself believe it was so. "He is asleep, Little John--let us lay him quietly upon his bed."

So died Robin Fitzooth, first Earl of Huntingdon, under treacherous hands. Nearby Kirklees Abbey they laid to his last rest this bravest of all brave men--the most fearless champion of freedom that the land had ever known.

Robin Hood is dead, and no man can say truly where his grave may be. At the least it but holds his bones. His name lives in our ballads, our history, our hearts--so long as the English tongue is known.

303:1 Carfax was then actually in France, acting against Richard.