Genealogical chart

AMONG the various characters introduced into the foregoing tale, none is more strictly and successfully maintained than that of Arthur. In him we see the dignified and noble-hearted sovereign, the stately warrior, and the accomplished knight, courteous of demeanour and dauntless in arms. And whilst the lofty bearing of the monarch himself excites our admiration, we are scarcely less struck with the devoted attachment evinced towards him by his knights, who are ever solicitous that he should be the last to encounter danger, and ever ready themselves to dare the most perilous adventures to uphold the dignity of his crown. But it is not merely the consistency observed in these several characters that arrests our attention in this and similar compositions professing to record the achievements of Arthur and his knights; we are also forcibly struck with the powerful influence which those legends exercised over society, and the ascendancy which their principal hero so decidedly maintained. Nor can we withhold our wonder at the singular destiny which has awaited this extraordinary being. Whilst by some his very existence has been called in question, his name has become celebrated throughout the civilised world; and his exploits, whether fabulous or real, have afforded the most ample and interesting materials to the poet, the antiquary, and the historian. To this very day the memory of the mighty warrior, "whose sword extended from Scandinavia to Spain," exercises a power over our imagination which we are as unable as we are unwilling to dispel. His image adorned our earliest visions of Chivalry and Romance, and though the weightier cares of maturer age must supervene, they serve but to deepen, not to efface the impression; and while in the eddying stream of life we pause to look back upon the days when Caerlleon and its Round Table formed to us an ideal

world, we feel that, in our hearts at least, "King Arthur is not dead."

The real history of this chieftain is so veiled in obscurity, and has led to so much unsatisfactory discussion, that I shall in this place only consider him with reference to the position which he occupies in the regions of Fiction.

Amongst the many incidents of a highly imaginative character, in the legendary history of Arthur, we may more particularly notice his introduction upon the scene of his exploits.

During the turbulent times which followed the death of Uther Pendragon, the nobles of Britain assembled to elect a successor to him, but, after protracted debate, they were unable to come to any decision upon the subject. At length a large stone was discovered near the place of assembly, in which was a sword fastened as it were in a sheath. Around it was an inscription in gold letters, signifying that whoever should draw out that sword was rightful heir to the throne. After all those who were ambitious of this dignity had made the attempt in vain, Arthur, who was previously unknown, came forward, and drew out the sword from the stone as easily as he would have drawn it out of the scabbard. He was thereupon immediately acknowledged king.

Being thus placed at the head of the Chivalry of Britain, he proceeded in a glorious and triumphant career, until, by the treachery of his nephew, Modred, he sustained a defeat in the battle of Camlan.

After witnessing the destruction of his army in that fatal conflict, Arthur, finding himself mortally wounded, delivered his sword to Caliburn one of his knights, with a request that he would cast it into a certain lake. The knight, thus commissioned, proceeded to the appointed spot, and, standing upon the bank, flung the sword forward with all his might. As it was descending, a hand and arm came out of the lake, and seizing it by the hilt brandished it three times, and disappeared with it in the water.

Arthur was afterwards conducted by the Knight to the border of the lake, where he found a little bark moored, in which were Viviane, the Lady of the Lake, and Morgan le Fay, and other ladies, who carried him off to the Island of Avalon, in Fairy-laud, where it was affirmed that he was healed of his wounds, and continued to live in all the splendour of that luxurious country, waiting for the time when he should return once more to take possession of his ancient dominions.

In confirmation of this idea it was asserted that the place of his

sepulture was not known. This tradition was current for many ages, and is found among the Welsh, in the Memorials of the Graves of the Warriors,--

"The grave of March is this, and this the grave of Gwythyr.

Here is the grave of Gwgawn Gleddyfrudd

But unknown is the grave of Arthur." 1

Our English ears are so familiarized with the name of King Arthur, that it seems impossible to give him the appellation of Emperor, by which he is designated in the original Welsh, and to which, according to the old Romances, he was fully entitled, since once upon a time, "at crystemas," he was crowned "Emperour with creme as it bylongeth to so hyhe astate."--Morte d'Arthur.

We find the title of Emperor bestowed upon Arthur in Llywarch Hên's Elegy upon Geraint ab Erbin.

"At Llongborth were slain to Arthur

Valiant men, who hewed down with steel;

He was the emperor, and conductor of the toil of war."

OWEN'S Heroic Elegies.

3b CAERLLEON UPON USK.--Page 3.

THIS place derives its name from the circumstance of its being the station of the Second Legion (Legio Secunda Augusta) during the dominion of the Romans. The name by which they originally called it was Isca Silurum, evidently from its situation upon the river Usk; but by later Latin writers it is named Urbs Legionum, which probably is a translation of the Welsh Caer-lleon, and not the original of that appellation. This place still exhibits many traces of Roman magnificence, and among others the remains of an amphitheatre. It is natural to suppose that, upon the departure of the Legions, Caerlleon would attract the attention of the native Sovereigns, who were at that time beginning to resume their power; accordingly, tradition informs us that it was the principal residence of King Arthur; and the amphitheatre is still called Arthur's Round Table. In confirmation of this traditionary evidence, Nennius asserts that one of Arthur's battles was fought at Cairlion.

In the old English version of this tale the opening scene is laid at Cardiff.

"He made a feste, the soth to say,

Opon the Witsononday,

At Kerdyf, that es in Wales."--line 17.

[paragraph continues] And on a subsequent occasion we find the City of Chester named--

"The kyng that time at Cester lay."--line 1567.

[paragraph continues] In the French Copy,-

"Q' li rois cort a cestre tint."

Of CHESTER it may be remarked, that it bears in Welsh the name of Caerlleon Gawr, which seems to indicate its having been the station of the Twentieth Legion, called Legio Vicesima Valens Victrix, the word Gawr being nearly equivalent to the Latin Valens.

3c OWAIN THE SON OF URIEN.--Page 3.

OWAIN AB URIEN RHEGED.--AMONGST all the characters of ancient British history, none is more interesting, or occupies a more conspicuous place, than the hero of this tale. Urien, his father, was prince of Rheged, a district comprising the present Cumberland and part of the adjacent country. His valour and the consideration in which he was held, are a frequent theme of Bardic song, and form the subject of several very spirited odes by Taliesin, particularly those upon the battles of Gwenystrad and Argoed Llwyfein, which are given, with English translations, in the Myvyrian Archaiology, i. 52, 3, 4. The name of Fflamddwyn, the flame-bearer, which occurs in these poems, is supposed to be that by which the Welsh designated Ida, the Anglian King of Northumberland. In the Appendix to Gale's Nennius, it is mentioned that Urien was one of the four Northern princes who opposed the progress of Deodric the Son of Ida. Urien besieged the latter in the island of Lindisfarne. The other princes were Rhydderch Hael, Gwallawc ap Llenawc, and Morcant, 1 the latter of whom being jealous of Urien's military skill, in which he is

said to have excelled all the other kings, procured his assassination during the expedition.

According to Llywarch Hen's Elegy upon Urien Rheged, this event occurred in a place called Aberlleu. 1

The Triads mention Llovan Llawdivo as the assassin. Of him little is known; but that he was a person of some note is evident from the circumstance of his grave being recorded.

"The grave of Llovan Llawdivo

is on the strand of Menai, where makes the wave a sullen sound." 2

"The Genealogy of the Saints records that Urien came into South Wales, and Was instrumental with the sons of Ceredig ab Cunedda, and his nephews, in expelling the Gwyddelians, who had gained a footing there from about the time of Maxen Wledig."--Camb. Biog.

The old Romancers connect him with South Wales, and call him King Uryens of Gore, evidently intended for Gower in Glamorganshire.

Thus it is recorded in the Morte d'Arthur, "Thenne the Kyng remeued in to Walys, and lete crye a grete feste that it shold be holdyn at Pentecost after the incoronacion of hym at the Cyte of Carlyon, vnto the feste come kyng Lott of Lowthean, and of Orkeney with fiue C knygtes with hym. Also there come to the feste kynge Uryens of gore with four C knyghtes with hym."

But to return to Owain; it appears from the manner in which he is always mentioned by contemporary Bards, that he greatly distinguished himself in his country's cause, subsequently to the death of his father, but with what ultimate success we are not acquainted.

There exists an ancient Poem, printed among those of Taliesin, called the Elegy of Owain ap Urien, and containing several very beautiful and spirited passages. It commences,

The soul of Owain ap Urien

May its Lord consider its exigencies,--

Reged's chief the green turf covers."

In the course of this Elegy, the Bard bursts forth with all the energy of the Awen,

"Could Lloegria sleep with the light upon her eyes?" 3

[paragraph continues] Alluding to the incessant warfare with which this chieftain, during his lifetime, had harassed his Saxon foes.

In the Myvyrian Archaiology (II. 80) we have the following Triad relating to him.

"Three Knights of battle were in the Court of Arthur; Cadwr, the Earl of Cornwall; Lancelot du Lac; 1 and Owain the son of Urien Rheged. And this was their characteristic, that they would not retreat from battle, neither for Spear, nor for Arrow, nor for Sword, and Arthur never had shame in battle, the day he saw their faces there, and they were called the Knights of Battle."

Owain is also mentioned with Rhun mab Maelgwn, and Rhufawn befr mab Deorath Wledig, as one of the Three blessed Kings; 2 and in the 52nd Triad, we are informed that his Mother's name was Modron, the daughter of Afallach, and that he was born a twin with his sister Merwydd, or Morvyth, to whom Cynon ap Clydno's attachment is well known.

His place of sepulture is thus mentioned in the Graves of the Warriors.

"The grave of Owain ap Urien is of quadrangular form,

Under the turf of Llan Morvael."

Frequent allusions are made to Owain by the Bards of the Middle Ages, especially by Lewis Glyn Cothi, who in an ode to Gruffudd ap Nicholas, a powerful chieftain of Carmarthenshire, and one of the descendants of Urien Rheged, has, among other things, the following passage:

"Gruffudd will give three ravens of one hue,

And a white lion to Owain, [his son]."--I. 133.

The Editor of the works of Glyn Cothi supposes that "this expression may allude to Griffith presenting his son with a shield, with his own arms emblazoned upon it, and the royal lion for a

crest," The three ravens undoubtedly apply to the armorial bearings of Urien Rheged, which are still borne by his descendants of the House of Dynevor; the lion also may have been an heraldic bearing of the family, but I am inclined to think that the Bard here intended an allusion to one of the principal incidents of the Lady of the Fountain. That he was acquainted with this Tale is evident, from some lines occurring in one of his Poems, addressed to Thomas ap Philip of Picton Castle, in which Owain and Luned are mentioned together.

In the early French compositions, called Lays and Fabliaux, Owain's name frequently occurs. He is mentioned in the Lay of Lanfal, and in Court Mantel, where he is particularized for his love of dogs and hawks.

"Li rois prit par la destre main

L'amiz monsegnor Ivain,

Qui au roi Urien fu filz,

Et bons chevaliers et hardiz

Qui tant ama chiens et oisiaux."

(Fab. MSS. du roi, n. 7615, fol. 114 recto, col. 3.)

He acts a conspicuous part in the Romances of the Round Table; and it is on such authority that Ste. Palaye celebrates him, "pour avoir introduit l'usage des fourrures ou zibelines aux manteaux, des ceintures aux robes, et des boucles pour attacher les éperons et Den, et pour avoir encore inventé la mode des gants."

3d KYNON THE SON OF CLYDNO.--Page 3.

CYNON AP CLYDNO EIDDIN.--This ancient British Warrior is celebrated in the Triads as one of the Three wisely-counselling Knights of Arthur's Court.

'Three counselling Knights were in the Court of Arthur, which were Cynon the son of Clydno Eiddin, Aron the son of Kynfarch ap Meirchion gul, and Llywarch hen the son of Elidir Lydanwyn. And these three knights were the Counsellors of Arthur, and whatever dangers threatened him in any of his wars, they counselled him, so that none was able to overcome Arthur; and thus he conquered all the nations through three things which followed him; and these were, Good hope, and the consecrated arms which had been sent him, and the virtue of his warriors; and through these he came to wear twelve crowns upon his head, and he became Emperor of Rome."

And in another place it is added,

"And he had nothing but success when he acted by the advice

which he received from them, and reverses when he did not follow their counsel."

Kynon is also called one of the three ardent Lovers, on account of his passion for Morvyth, daughter of Urien Rheged, and sister of Owain, the Hero of this Tale.

"The three ardent lovers of the Island of Britain, Caswallawn the son of Beli for Flur the daughter of Mugnach Gorr, and Trystan the son of Talluch for Yseult the wife of March Meirchawn his uncle, and Kynon the son of Clydno Eiddin for Morvyth the daughter of Urien."

This warrior is mentioned by Aneurin,

"And Kynon------like rushes they fell before his hand.------

O son of Clydno, a song of lasting praise will I sing unto thee."

And it is probable that he was one of the three, who, together with the Bard himself, escaped from the disastrous battle of Cattraeth.

The Warriors who went to Cattraeth were renowned;

Wine and Mead out of golden goblets was their beverage.

That year was to them. one of exalted dignity,

Three warriors and three score and three hundred, wearing the golden torques-------

Of those who marched forth after the excess of revelling,

But three escaped from the conflict of gashing weapons;

The two War-dogs of Aeron and Kynon the dauntless,

(And I myself from the spilling of blood) worthy are they of my song."

Gray has given a poetical version of this passage in his fragments, commencing with the words, "To Cattraeth's vale in glittering row."

Also, in another poem by Aneurin, named the Gwarchan (or Incantation) of Cynvelyn, are the following lines:

"Three Warriors and three score and three hundred,

To the conflict of Cattraeth went forth.

Of those who hastened from the banquet of mead,

Three only returned,

Kynon, and Kadreith, and Katlew of Catnant,

And I myself from the shedding of blood."

Kynon is frequently mentioned by the bards of the Middle Ages, and celebrated both for his bravery and for his devotion as a lover.

[paragraph continues] It is in the latter character that be is alluded to by Gruffudd ap Meredith, in the beginning of the fourteenth Century, who compares the force of his own passion to that of Kynon for Morvyth, and that of Uther Pendragon for the fair Ygrayne.

"As the sigh of Uther for the love of Ygraine, the fair and splendid,

And the sigh of Kynon for the love of the beauteous daughter of Urien,

Such is the sigh of the bard for the lovely object of his affections.

Myv. Arch.

In the Memorials of the Graves of the Warriors, the following stanza records the place of the sepulture of Kynon.

"The grave of a warrior of high renown

Is in a lofty region--but a lowly bed,

The grave of Kynon the son of Clydno Eiddin."

In another stanza, the term lowly bed seems to be explained, and it would appear that a little hollow among the mountains was meant:

Whose is the grave beneath the hill?

It is the grave of a warrior valiant in the conflict

The grave of Kyrion the son of Clydno Eiddin."

CLYDNO EIDDIN, the father of Cynon.--But little is known of the history of this Chieftain, although as late as the fourteenth Century, his name is found recorded by the Bards, in such terms as to make it evident that he still continued to occupy a place of considerable distinction among the heroes of the Principality, as may be seen in a poem by Risierdyn, a bard who flourished about the year 1300. In this poem, which records the burial of Hywel ap Gruffudd in the Church of St. Benno, that Warrior is compared in point of bravery, to Clydno.

"The red-weaponed chief, the ruler of the golden region of costly wine,

Saint Beuno's blessed choir now conceals;

The mighty high-famed leader, daring as Clydno.

Silent are his remains within their oaken cell."

Myv. Arch. I. 432.

3f KAI THE SON OF KYNER.--Page 3.

CAI AP CYNYR.--According to the Welsh pedigrees, Kai was the son of Cynyr Cainvarvawc, the son of Gwron, the son of Cunedda Wledig. In the Triads he is called one of the three diadem'd chiefs of battle, and is said to have been possessed of magical powers, by which he could transform himself into any shape he pleased. 1 Of his real history, however, nothing is known. It is supposed that Caer Gai, in North Wales, bear his name; and it was the opinion of Iolo Morganwg, that the place of his sepulture was at Cai Hir, at Aberavan, in Glamorganshire.

In the Brut he is called the Dapifer, or Sewer of King Arthur. And in the French Romances he is mentioned as the Seneschal, and is styled Messire Queux, and Maitre Queux, or Keux--the original name being evidently altered in this manner in order to adapt it to his office of Chief of the Cooks. In these productions, his general character is a compound of valour and buffoonery: always ready to fight, and generally getting the worst of the battle.

There is much that is very entertaining concerning him in the Morte d'Arthur, particularly a story of his want of courtesy to Sir Gareth, Gwalchmai's (Gawain's) brother, which led him into trouble.

"Whan Arthur held his round table moost plenour, it fortuned that he commaunded that the hyhe feest of Pentecost shold be holden at a cyte and a Castel the whiche in tho dayes was called kynke kenadonne upon the sondes that marched nyghe walys." Upon this occasion, a youth who would not declare his name, presented himself before Arthur, and craved a boon, which the monarch immediately promised to grant. The boon he asked was, that he should be allowed meat and drink for the space of a twelvemonth in the King's palace. This the King considered a very unworthy petition, and counselled him to ask something more honourable, but the youth still persisted in his request. "Well sayde the kynge ye shal haue mete and drynke ynouz, I neuer deffended yt none, nother my frende ne my foo." "Thenne the kyng betook hym to sir Kay the steward and charged hym that he shold gyue hym of al manner of metes and drynkes of the best, and also that he hadde al maner of fyndynge as though he were a lordes sone. That shal lytel nede sayd syr Kay to doo suche

cost upon hym. For I dare undertake he is a vylayne borne, and neuer will make man, for and he had come of gentylmen he wold haue axed of you hors and armour, but such as he is so he asketh. And sythen he hath no name, I shall yeue hym a name that shall be Beaumayns that is fayre handes, and in to the kechen I shalle brynge hym, and there he shalle haue fatte broweys euery day yt he shall be as fatte by the twelue monethes ende as a porke hog." So Sir Kai "scorned hym and mocked hym."

At the end of the twelvemonth, Beaumayns desired to be knighted, in order to achieve a certain perilous adventure; 1 and Sir Kai called him a "kechyn knave." And when the young man left the Court, to set out on his expedition, Kai armed himself and followed him, thinking to vanquish him without difficulty, and bring him to disgrace. But Beaumayns unhorsed Sir Kai, and took possession of his arms, with which he performed several gallant exploits to the great surprise of all, inasmuch as he was taken by his shield to be Sir Kai, whose prowess was by no means in high repute. Afterwards Beaumayns proved to be Sir Gareth of Orkney, the son of King Lot, and brother of Sir Gawain.

ACCORDING to the Welsh Legends, Arthur had three queens, one of whom was daughter of Gwythyr ap Greidiol, another of Gwryd Gwent, and a third of Gogyrvan Gawr; and each of them bore the name of Gwenhwyvar. Concerning the latter lady, 2 the following couplet is still current in the Principality:--

"Gwenhwyvar, the daughter of Gogyrvan the Giant,

Bad when little, worse when great."

This confusion of names and persons is only what might be expected from the mass of traditionary matter that has accumulated among the Welsh. As the exploits of Arthur began to assume a fabulous character, it is evident that many of the more ancient legends of Britain became blended with those of the Round Table, and perhaps

some of the mythological traditions of the Druidic age are to be found amongst them. This continual accession of fable tends to render still more obscure that which a redundancy of imagination had already sufficiently involved.

The name of Gwenhwyvar, under the various forms of Guenever, Genievre, and Geneura, must be familiar to all who are conversant with chivalric lore. And it is to her adventures, and those of her true knight, Sir Lancelot, that Dante alludes in the beautiful episode of Francesca da Rimini.

THE absence of a Porter was formerly considered as an indication of hospitality, and as such is alluded to by Rhys Brychan, a bard who flourished at the close of the fifteenth century.

"The stately entrance is without porters,

And his mansions are open to every honest man."

Lewis Glyn Cothi also (about 1450), in an eulogium upon Owain, the son of Gruffudd ap Nicholas, says, that his establishment was complete in every respect, with the exception of a Porter:--

"Every officer there is to the great Knight

Of the South, except a Porter."--I. 139.

3i GLEWLWYD GAVAELVAWR.--Page 3.

"THE dusky hero of the mighty grasp" is said to have escaped from the battle of Camdan by means of his extraordinary strength and stature. There is nothing of his real history known: indeed, from the construction of his name, he appears to be altogether a fictitious character; and it is not impossible that he may be one of those mythological personages who formed the subjects of the Welsh legendary tales, before the adventures of Arthur had assumed the character of fiction, and that when those adventures became objects of fabulous composition, this and other ancient Druidical traditions were incorporated with them.

Among the Bardic remains there is a poem, called a Dialogue betwixt Arthur and Kai, and Glewlwyd, some lines in which are considered by Davies to have reference to some Druidical mysteries. Although it may appear presumptuous to differ from

so high an authority, I shall venture to give the following translation-

"Who is the Porter?

Glewlwyd Gavaelvawr.

Who is it that asks?

Arthur and the blessed Kai.

If thou shouldst bring with thee

The best wine in the world,

Into my house thou shalt not come,

Unless it be by force, &c."

3j ON A SEAT OF GREEN RUSHES.--Page 3.

THE use of green rushes in apartments was by no means peculiar to the Court of Caerleon upon Usk. Our ancestors had a great predilection for them, and they seem to have constituted an essential article, not only of comfort but of luxury. The custom of strewing the floor with rushes is well known to have existed in England during the Middle Ages, and that it also prevailed in the Principality we have evidence from allusions which occur in the works of native writers. Of this, one example will suffice, from a tale written apparently in the 14th Century; and as the passage contains several curious traits of ancient manners, I shall give it at some length.

In this tale Davydd ap Owain Gwynedd, Prince of North Wales, wishing to send an embassy to Rhys, Prince of South Wales, and having fixed upon Gwgan the Bard as a proper person for that mission, despatches a messenger called y Paun Bach (the Little Peacock) in search of him. This person, after a long and tedious journey, arrives towards the close of evening at a house in a wooded valley, where he hears the tuning of a harp. From the style of playing, and the modulation, he supposes that the performer can be no other than Gwgan himself. In order to ascertain if his surmise is correct, be addresses him in a rambling high-flown style of language. The Bard answers him in the same strain, and asks him what he requires. To which Y Paun Bach thus replies:--"I want lodging for to-night ...... And that not better than I know how to ask for. ...... A lightsome hall, floored with tile, and swept, in which there has been neither flood nor rain-drop for the last hundred years, dressed with fresh green rushes, laid so evenly that one rush be not higher than the other the height of a gnat's eye, so that my foot should not slip either backward or forward the space of a mote in the sunshine

of June. Then I would have a chair with a cushion beneath me, and a pillow under each elbow," 1 &c. Y Paun Bach then goes on to describe the entertainment he desires to have. The fire is to be of ashen billets, without smoke or sparks; and the supper is to consist of wine, and swans, 2 and bitterns, and sundry spiced collops besides; and the servants, all dressed in one livery, 3 are to ply him continually with ale, and urge him to drink, for his own good and the honour of his entertainers.

In France, the practice of strewing rushes on the floor was also prevalent. We find the Seigneur Amanieu des Escas giving his instructions to the young men of his household on the Art of Love, "dans sa salle bien jonchée."--Poésies Provençales, cited by Ste. Palaye, I. 453.

3k FLAME-COLOURED SATIN.--Page 3.

THE literal translation of this expression is yellow-red. With regard to this mixture of colours, Ellis, in his notes to Way's Fabliaux, remarks, "The old French writers speak also of pourpre and écarlate blanches (white crimson); of pourpre sanguine (sanguine crimson); and, in the Fabliau de Gautier d'Aupais, mention is made of "un vert mantel porprin, (a mantel of green crimson)." Hence, M. Le Grand conjectures, "that the crimson dye being, from its costliness, used only on cloths of the finest manufacture, the term crimson came at length to signify, not the colour, but the texture, of the stuff. Were it allowable to attribute to the Weavers of the Middle Ages the art now common amongst us, of making what are usually called shot silks (or silks of two colours, predominating interchangeably as in the neck of the drake or pigeon), the contradictory compounds above given (white crimson, green crimson, &c.) would be easily accounted for." II. 227.

LITERALLY, "desert places, and the extremities of the earth." It is possible that some peculiar district of romantic geography was intended to be here alluded to, since we find that "la terre deserte" was formerly a kingdom of no inconsiderable importance, the sovereign of which, named Claudas, overran the territories of King Ban of Benoic, one of Arthur's allies in Gaul. And in the Morte d'Arthur, it is said that Arthur, being wounded in the battle of Camlan, was conveyed to the Island of Avalon "in a shyppe wherin were thre quenes, that one was kyng Arthurs syster quene Morgan le fay, the other was the quene of North galys, the thyrd was the quene of the waste londes. Also there was Nynyue (Viviane) the chyef lady of the lake," &c.

4b TREES OF EQUAL GROWTH.--Page 4.

THIS species of scenery appears to have been much admired by our ancestors.

A similar description occurs in a chivalric tale of considerable interest, by Gruffydd ab Adda, a Bard who was killed at Dolgellau, about 1370.

"In the furthermost end of this forest he saw a level green valley, and trees of equal height, &c."

Chaucer describes a bower in the same style, in his Flour and Leaf. It was composed of "sicamour and eglatere,"

Wrethen in fere so well and cunningly

That every branch and leafe grew by mesure

Plaine as a bord, of an height by and by."

The whole account which he gives us of the "pleasaunt herber" is very poetical, particularly the following beautiful lines, descriptive of the avenues of "okes" which led to it.

"In which were okes great, streight as a line,

Under the which the grasse so fresh of hew

Was newly sprong, and an eight foot or nine

Every tree well fro his fellow grew,

With branches brode, laden with leves new,

That sprongen out agen the sunne-shene,

Some very red, and some a glad light grene."

PALI MELYN.--The exact signification of the word Pali in the original is not quite obvious, as it sometimes seems to imply satin and sometimes velvet, according to the rank of the persons who are represented as wearing it. Nor is the question so immaterial as at first sight it may appear; for, in the best days of Chivalry, the most exact etiquette was observed by the different grades of society with regard to the materials of which their dress was composed. Ste. Palaye mentions that, on occasions where the Knights wore cloth of damask, the Squires were restricted to dresses of satin; and where the Knights were clothed in velvet, the Squires could only appear in cloth of damask. The colour of scarlet was permitted to be worn only by Knights. (I. 247, 283.)

5a SINEWS OF THE STAG.--Page 5.

MOSELEY, in his work upon Archery, says that "bowstrings were composed from the sinews of beasts, and on that account are termed 'Nervus,' νευρά." "It was customary for this purpose," says he, "to select the sinews of several of those kinds of animals remarkable for their strength or activity, such as Bulls, Lions, Stags, &c., and from those particular parts of each animal in which their respective strength was conceived to lie. From Bulls, the sinews about the back and shoulders were collected; and from Stags, they took those of the legs."

5b BONE OF THE WHALE.--Page 5.

A SIMILAR substance is mentioned in the ancient Romance of "The Erle of Tolous,"--

"Hur hondys whyte as whallys bonne,"--verse 355.

[paragraph continues] Upon which Ritson has the following note:--"This allusion is not to what we now call whale-bone, which is well known to be black, but to the ivory of the horn or tooth of the Narwhal, or Sea-unicorn, which seems to have been mistaken for the whale. The similé is a remarkable favourite. Thus, in Syr Eglamour of Artoys,

"The erle had no chylde but one,

A mayden as white as whalës bone.'

Again, in Syr Isembras,

'His wyfe as white as whalës bone.'

Again, in 'The Squyr of low degree,'

'Lady as white as whalës bone.'

It even occurs in Skelton's and Surrey's Poems; and, what is still more extraordinary, in Spenser's Faëry Quene, and Shakespeare's Love's Labour Lost (if, in fact, that part of it ever received the illuminating touch of our great dramatist). Mister Steevens, in his Note on the last instance, observes that whales 'is the Saxon genitive case,' meaning that it requires to be pronounced as a dissyllable (thus, whalës, or, more properly, whaleës), which it certainly is, in every instance."--Rit. Met. Rom. III. 343, 344.

5c WINGED WITH PEACOCK'S FEATHERS.--Page 5.

THAT it was fashionable to feather arrows in this manner, we learn from the following description of the Yeman who attended upon the Knight, in the Prologue to Chaucer's Canterbury Tales.

"A shefe of peacock arwes bright and kene

Under his belt he bare ful thriftily,

Wel coude he dresse his takel yemanly:

His arwes drouped not with fetheres low,

And in his hond he bare a mighty bowe."--line 104-8.

In a Wardrobe account, 4th of Ed. II., the following entry occurs "Pro duodecim flecchiis cum pennis de pavone emptis pro rege, de

[paragraph continues] 12 den'." For twelve arrows with peacock's feathers, bought for the King, twelvepence.

There was much art and care required in the construction and feathering of arrows. That the Welsh archers paid much attention to their equipments may be seen in an interesting passage from the composition already noticed, p. 43. In this Tale the messenger from the Court of North Wales, who appears to be a skilful archer, on being told by Gwgan the Bard that a robber will ride away with his horse, answers, "But what if I were opposite to him in yonder Wood, with a bow of red yew in my hand, ready bent, with a tough tight string, and a straight round shaft with a compass-rounded neck, and long slender feathers fastened on with green silk, and a steel head heavy and thick, and an inch across, of a green blue temper, that would draw blood out of a weathercock; and with my foot to a hillock, and an oak behind me, and the wind to my back, and the sun to my side, and the maid I love best on the footpath hard by looking at me, and I conscious of her being there; then would I shoot him such a shot, so strong and long-drawn, so low and sharp, that it would be no more avail to him there were between him and me a breastplate and Milan hauberk, than a tuft of fern, or a kiln mat, or a herring net."

It is well known that bows and arrows formed a subject of legislation in England, and among the Welsh Laws we find the following clause---

"Three weapons by law:--A sword, a spear, and a bow with twelve arrows in a quiver. And it is required of every master of a family to keep them in readiness against the attacks of a foreign army, and of strangers, and other depredators."

5d GOLDEN HEADS.--BLADES OF GOLD.--Page 5.

To Knights and to their families was exclusively confined the privilege of decorating their dress, their arms, and the accoutrements of their horses with gold; Squires being only permitted the use of silver.--Ste. Palaye, I. 247, 283. By the sumptuary laws of Ed. III. (an. 27. c. ix. x. xi. xii.) Esquires were to possess property of at least 200 marks yearly value, before they could be permitted to wear "cloth of silk and of silver, ribband, girdle, and other apparel reasonably garnished with silver." And Knights, their wives, daughters, and children, were not entitled to wear "cloth of gold, nor cloths, mantle, nor gold furred with miniver, nor of ermins, nor

no apparel bordered of stone, nor otherwise," if their possessions were below the yearly value of 251 marks. But to such Knights and Ladies as possessed 400 marks annually, there was no restriction as to dress, except with respect to "ermins and letuses and apparel of pearl and stone," which they might only wear upon the head. Merchants and burgesses of 500 marks had the same privilege of dress as Esquires of 200 markland. Hence perhaps it may be inferred that the two Youths mentioned in this Tale were of knightly origin.

That the gilding of bows was customary in the 14th Century, we have the authority of Davydd ap Gwilym. In lines addressed to his fair countrywomen against gaudiness of dress, and which have been thus elegantly rendered by Arthur Johnes, Esq., in his Poetical Translation of the Works of that celebrated Bard, he says:--

"The vilest bow that e'er was framed of Yew,

That in the hand abruptly snaps in two,

When all its faults are varnished o'er with gold,

Looks strong, and fair, and faultless, and--is sold."--(p. 412.)

Lewis Glyn Cothi has the following line,

"With gold shall be adorned thy fingers, thy sword, and thy mantle."

And examples might be multiplied to almost any extent.

Where arrow-heads, and the blades of weapons are mentioned as golden, it is very evident that in many instances steel inlaid with gold is meant. Thus, the Bard above alluded to says,--

"A gold Brigandine like the casting of a Dragon's skin."

And subsequently this gold Brigandine is said to be of steel,--

Good is the band of this steel vestment.--(I. 158.)

5e VARIEGATED LEATHER.--Page 5.

CORDWAL.--This word occurs in another of the Mabinogion; and from the manner that it is used, it is evidently intended for the French Cordouan, or Cordovan leather, which derived its name from Cordova, where it was manufactured.

5f DAMSELS EMBROIDERING SATIN.--Page 5.

IN the English Romance of "Ywayne and Gawain," paraphrased from the French "Chevalier an Lyon," we find a similar picture. In a beautiful city, named in English the "Castel of the Hevy Sorrow," and in the French the "Chastel de Pesme Auenture," the hero, Ywayne or Owen, finds a number of ladies, "wirkand silk and gold wir." They are very meanly attired, and inform Owen that they were once of great estate in the country of Mayden-land, whence they were sent as hostages by their sovereign. They complain that they have to work very hard, and for a very slight remuneration; the best of them receiving only "four penys" in a week, which was scarce sufficient to maintain them, whereas they consider that they might earn "fourty shilling."

5f MORE LOVELY THAN GWENHWYVAR.--Page 5.

THIS was the highest compliment that Kynon could pay to the beauty of these four-and-twenty damsels, since Gwenhwyvar is celebrated in the Triads (with Enid and Tegau Euron,) as one of the three fair ladies of Arthur's Court.

Lewis Glyn Cothi, in extolling the charms of Annes, the daughter of John, of Caerlleon upon Usk, has the following allusion to this Triad:--

The beauteous and amiable Annes is where Tegau was,

Where Gwenhwyvar was, with all her charms;

Where Enid was seen, wearing azure robes,

Where the Castle of the valorous Arthur stands."

5g THEY ROSE UP AT MY COMING.--Page 5.

IT was very usual in the chivalric days, for the ladies to perform those courteous offices for the Knights, even where there were male attendants, to whom we may consider that they would have been more appropriately assigned. Ste. Palaye tells its, "Les jeunes demoiselles . . . . prévenoient de civilité les chevaliers qui arrivoient dans les châteaux; suivant nos romanciers, elles les désarmoient au retour des tournois et des expéditions de guerre, leur donnoient de nouveaux habits et les servoient à table. Les exemples en sont trop souvent et trop uniformément répétés, pour nous permettre de révoquer en doute la réalité de cet usage." (I. 10.) I should imagine, however, it was the absence of male assistance that induced the damsels in Kynon's story to extend their cares to his horse, for I am not aware that in general their courtesy went so far.

5h GOLD BAND UPON THE MANTLE.--Page 5.

THE word in the original Welsh is gorffoys, which is evidently the same as orfrays, or aurifrigia. 1 This was a kind of fretwork, or embroidery of gold, and is mentioned thus in the playful description of the allegorical figure of Idlenesse, which occurs in the Romaunt of the Rose:

"And of fine orfrais had she eke

A chapelet, so semely on,

Ne wered never maide upon;

And faire above that chapelet

A rose garlonde had she set."--562-6.

DRINKING-HORNS of this material are frequently mentioned by the Bards, and appear to have been made use of by the Welsh in all their banquets. There is still extant in the Welsh language, a spirited poem by Owain Kyveiliog, Prince of Powis, called the Hirlas, a name by which his drinking-horn was known, and which he describes as

"The highly honoured buffalo-horn Hirlas, enriched with ancient silver."

In the course of this poem, one passage occurs of a highly dramatic character. The Prince having sent round the horn to several chieftains, at length orders it to be filled with the choicest beverage, and borne to Tudur and Moreiddig, at the same time expatiating with gratitude and admiration upon their valour, and the eminent services they had tendered him in the arduous conflicts ill which he had been engaged. Turning round in the fulness of his heart to address them personally, he perceives their places vacant; and suddenly recollecting that they had both fallen in one of the late encounters, he bursts out in a pathetic strain of lamentation, "The wail of death has been heard, they both have departed!--O, lost Moreiddig, how greatly shall I miss thee!"

THIS description answers to that of the Fountain of Barenton, in the forest of Breceliande, to which locality it is referred in the

[paragraph continues] "Chevalier au Lion." 1 Breceliande is in Brittany, and is the fabled scene of Merlin's imprisonment, by the enchantments of his Mistress Viviane, the Lady of the Lake. Within the precincts of this Forest also lay the Val sans Retour, or the Vallon des Faux Amans.

An amerawd was the stane,

Richer saw i never nane,

On fowr rubyes on heght standand,

Their light lasted over al the land."--line 364.

10a AN ADVENTURE SO MUCH TO HIS OWN DISCREDIT.--Page 10.

BY the laws of Chivalry, the knights were under a solemn obligation, when relating their adventures, to give a faithful account of what befell them, without concealing anything, however disadvantageous to themselves.

10b UNCOURTEOUS SPEECH.--Page 10.

SIR KAI'S uncourteous speech was proverbial. In Ywain and Gawin, we are told,

"And than als smertly sayd Sir Kay;

He karpet to tham wordes grete."

And so rude was his manner, that at length

"The quene answered, with milde mode,

And said, Sir Kay, ertow wode?

What the devyl es the withyn,

At thi tong may never blyn

Thi felows so fowly to shende?

Sertes, sir Kay, thou ert unhende."--line 488.

10c HORN FOR WASHING.--Page 10.

IT was customary to prepare for dinner by washing the hands, and the summons for this preparation was given by sounding a horn, which, by the French, was termed corner l'eau, or corner l'eue. Amongst the Monks, the same notice was given by ringing a bell.

We have the name of the Black Knight given us both in the English and in the French version. In the former, the appellation of Salados the rouse is bestowed upon him, and in the latter he is called Elcadoc le rous, which bears some resemblance to the Welsh Cadoc or Cattwg.

THIS maiden, whose name we subsequently find to be Luned, is supposed, in the Notes to Jones's Welsh Bards, to be the same person as Elined the daughter of Brychan; although from the accounts transmitted to us of that illustrious lady, she appears to have differed much in disposition and pursuits from the handmaid of the Lady of the Fountain. Mr. Rees, in his valuable Essay on the Welsh Saints, has the following notice concerning her:--

"Elined, the Almedha of Giraldus Cambrensis, who says that she suffered martyrdom upon a hill called Penginger, near Brecknock, which the Historian of that County, so often quoted, identifies with Slwch.

'Crug gorseddawl,' 1 mentioned after the name of Elined in the Myvyrian Archaiology, has been taken for Wyddgrug, or Mold, in Flintshire; but it may be no more than a descriptive appellation of Slwch, on which there were lately some remains of a British Camp. Cressy, speaking of St. Almedha, says, 'This devout virgin, rejecting the proposals of an earthly prince, who sought her in marriage, and espousing herself to the eternal king, consummated her life by a triumphant martyrdom. The day of her solemnity is celebrated every year on the firstday of August.'"--(149-50.)

The beauty of Luned was much celebrated amongst the Bards of the Middle Ages. Gruffudd ap Meredydd, who flourished between 1290 and 1340, thus alludes to her charms, in an Elegy on Gwenhwyvar of Anglesey:--

"Alas, for the loss of her who was equal to Luned, that gem of light!"

And Dafydd ap Gwilym mentions her in the same strain.

She is in the French Romances generally called Lunette, and in the Morte d'Arthur she acts a conspicuous part in the story of Sir Gareth of Orkney, who undertook the adventure of the "Castel

peryllous" on her behalf, and whose illtreatment by Sir Kai is related, p. 40. Sir Gareth took his full revenge upon Sir Kai, but his conduct under the taunts he received from Luned, who called. him a kechen knaue, and used towards him very discourteous language, considering that he was taking up her quarrel, is generous and high-minded in the extreme. It ended in Sir Gareth marrying Luned's sister, Dame Lyones, of the Castel peryllous; and in Luned herself, who is also called the "daymoysel saueage," becoming the wife of Sir Gaherys, who was Sir Gareth's brother. And these nuptials were solemnized with great pomp and splendour at King Arthur's Court. See Morte d'Arthur, Book VII. Compare Mr. Tennyson's poem of Gareth and Lynette in the Idylls of the King.

13a WHATEVER IS IN MY POWER.--Page 13.

IT appears rather extraordinary at first sight that Luned should take so lively an interest in Owain, and give herself so much trouble to forward his suit with the Countess, and also that she should express herself so well acquainted with his character. But from the English Metrical Romance, we find that they were old friends, Luned having been on an embassy to Arthur's Court some time previously.

THE ring is enumerated among the "Thirteen Rarities of Kingly Regalia of the Island of Britain, which were formerly kept at Caerlleon, on the river Usk, in Monmouthshire. These curiosities went with Myrddin the son of Morvran, into the house of Glass, in Enlli, or Bardsey Island. It has also been recorded by others that it was Taliesin, the Chief of the Bards, who possessed them."

"The Stone of the Ring of Luned, which liberated Owen the son of Urien from between the portcullis and the wall. Whoever concealed that stone, the stone or bezel would conceal him."

The properties of this magical ring, will, doubtless, call to mind the ring of Gyges, which was most probably the prototype from which it was indirectly derived.

ELLIS, in his Notes to Way's Fabliaux, has the following remarks upon horseblocks, which are mentioned in a vast number of the old Romances: "They were frequently placed on the roads and in the forests, and were almost numberless in the towns. Many of them still remain in Paris, where they were used by the magistrates in order to mount their mules, on which they rode to the courts of

justice. On these blocks, or on the tree which was generally planted near them, were usually suspended the shields of those Knights who wished to challenge all comers to feats of arms. They were also sometimes used as a place of judgment, and a rostrum, on which the barons took their seats when they determined the differences between their vassals, and from whence the publick criers made proclamations to the people."--(II. 229.)

13d PAINTED WITH GORGEOUS COLOURS.--Page 13.

THIS custom of painting figures upon the panels of rooms was much practised and esteemed at the time when we may suppose that this Tale was put into its present dress. Chaucer has several instances, of which we may notice more particularly the allegorical figures on the wall, at the opening of the Romaunt of the Rose, and the far more interesting and descriptive representations in the Temples of Mars, Venus, and Diana, in the "Knightes Tale." The paintings at the Temple of Mars were executed with so much art that even sounds were emitted by them.

"First on the wall was peinted a forest

In which ther wonneth neyther man ne best

With knotty knarry barrein trees old

Of stubbes sharpe and hidous to behold,

In which ther ran a romble and a swough,

As though a storme shuld bresten every bough," &c.--(1977.)

THIS Word is the same as that in the original Welsh, and is used by the old writers to signify a thin kind of silk like cyprus. The dress of the "Doctour of Phisike," one of the pilgrims to Canterbury, was, no doubt, a handsome one, and of him we are told--

"In sanguine and in perse he clad was alle

Lined with taffata and with sendalle."--(441.)

15b SHE WASHED OWAIN'S HEAD.--Page 15.

HOWEVER these personal services may appear to be at variance with the manners of the present day, it is clear that they were in perfect accordance with those of our ancestors. Of this, the following passage from the Life of Merlin will afford an example:--

"When. they went to the palace and had disarmed themselves,

[paragraph continues] King Leodagan made his daughter Genievre (Gwenhwyvar) take the richest cloths which were in the house, and warm water, and fair basins of silver, and made them be placed before King Arthur, and King Ban, and King Boors; and his daughter would wait upon Arthur, and would wash his neck and his face; but he would not allow thereof, till Leodagan and Merlin requested him, and made him accept the lady's service. The damsel washed his face right humbly, and then she wiped it with a fine towel, full gently; and then she went and ministered in like manner to the other twain."

THE English Version gives this Countess the title of

"The riche lady Alundyne,

The dukes doghter of Landuit."--line 1255.

And it is very satisfactory to find that she was not that Penarwen, daughter of Culfynawyt Prydein, who is mentioned as Owain's wife in the Triads, though in terms which are anything but complimentary. Perhaps Penarwen may have been a subsequent wife, since we may infer that Owain survived the Lady of the Fountain, from the circumstance so naively mentioned in the text, of her continuing to be his wife as long as she lived.

In Owen's Llywarch Hên, it is stated that after the death of Penarwen, Owain, was married to Denyw, the daughter of Llewddyn Luyddawg of Edinburgh, by whom he had Kendeyrn Garthwys, the celebrated St. Kentigern, who founded the Cathedral at Glasgow.

18a HER NUPTIALS WITH OWAIN.--Page 18.

THIS trait of manners is very characteristic of the times in which the present Tale was written. It was very usual for widows and heiresses in the troublous days of Knight-errantry to marry those whose strength and valour rendered them best able to defend and preserve to them their possessions. Ste. Palaye, in enumerating the advantages of the order of Knighthood, does not forget to mention this easy mode of advancing to fortune.--(I. 267, 326.)

18b GWALCHMAI.--Page 18.

GWALCHMAI AP GWYAR.--This ancient British name, Gwalchmai, which signifies the Hawk of Battle, is in the French Romances changed

into the not very similar form of Gawain, having first been Latinized into Walganus and Walweyn. In the Triads, he is mentioned in the following manner:--

"There were three golden-tongued Knights in the Court of Arthur: Gwalchmai the son of Gwyar; Drudwas the son of Tryffin, and Eliwlod the son of Madog ap Uthur. For there was neither King, nor Earl, nor Lord, to whom these came, but would listen to them before all others; and whatever request they made, it would be granted them, whether willingly or unwillingly; and thence were they called the Golden Tongued."

As a proof of the high estimation in which Gwalchmai's powers of persuasion were held, the following translation from the Myvyrian Archaiology (I. 178) may be adduced:--

HERE ARE ENGLYNS

Between Trystan the son of Tallwch, and Gwalchmai the son of Gwyar, after Trystan had been absent three years from Arthur's Court, in displeasure, and Arthur had sent eight-and-twenty warriors to seize him, and bring him to Arthur, and Trystan smote them all down, one after another, and came not for any one, but for Gwalchmai with the Golden Tongue.

GWALCHMAI.

Tumultuous is the nature of the wave,

When the sea is at its height--

Who art thou, mysterious warrior?

TRYSTAN.

Tumultuous are the waves and the thunder.

In their bursting forth let them be tumultuous.

In the day of conflict I am Trystan.

GWALCHMAI.

Trystan of the faultless speech,

Who, in the day of battle, would not retreat,

A companion of thine was Gwalchmai.

TRYSTAN.

I would do for Gwalchmai in that day,

In the which the work of slaughter is let loose,

That which one brother would not do for another. p. 58

GWALCHMAI.

Trystan, endowed with brilliant qualities,

Whose spear has oft been shivered in the toil of war,

I am Gwalchmai the nephew of Arthur.

TRYSTAN.

Gwalchmai, there swifter than Mydrin,

Shouldst thou be in danger,

I would cause blood to flow till it reached the knees.

GWALCHMAI.

Trystan, for thy sake would I strive

Until my wrist should fail me;

Also for thee I would do my utmost.

TRYSTAN.

I ask it in defiance,

I ask it not through fear,--

Who are the warriors before me?

GWALCHMAI.

Trystan, of distinguished qualities,

Are they not known to thee?

It is the household of Arthur that comes.

TRYSTAN.

Arthur will I not shun,

To nine hundred combats will I dare him,--

If I am slain, I will also slay.

GWALCHMAI.

Trystan, the friend of damsels,

Before commencing the work of strife,

The best of all things is peace.

TRYSTAN.

Let me but have my sword upon my thigh,

And my right hand to defend me,

And I myself will be more formidable than they all.

GWALCHMAI.

Trystan of brilliant qualities,

Before exciting the tumult of conflict,--

Reject not Arthur as a friend. p. 59

TRYSTAN.

Gwalchmai, for thy sake will I deliberate,

And with my mouth I utter it.

As I am loved, so will I love.

GWALCHMAI.

Trystan, of aspiring mind,

The shower wets a hundred oaks.

Come to an interview with thy kinsman.

TRYSTAN.

Gwalchmai, of persuasive answers,

The shower wets a hundred furrows.

I will go where'er thou wilt.

Then came Trystan with Gwalchmai to Arthur.

GWALCHMAI.

Arthur, of courteous replies,

The shower wets a hundred heads.

Here is Trystan, be thou joyful.

ARTHUR.

Gwalchmai, of faultless answers,

The shower wets a hundred dwellings.

A welcome to Trystan, my nephew.

Worthy Trystan, chief of the host,

Love thy race, remember the past

Am I not the Chief of the Tribe?

Trystan, leader of onsets,

Take equal with the best,

But leave the sovereignty to me.

Trystan, wise and mighty chieftain,

Love thy kindred, none shall harm thee,

Let there be no coldness between friend and friend.

TRYSTAN.

Arthur, to thee will I attend,

To thy command will I submit,

And that thou wishest will I do.

In one Triad we find Gwalchmai extolled as one of the three most courteous men towards guests and strangers; and from another we learn that be added scientific attainments to his other remarkable qualities.

"The three learned ones of the island of Britain, Gwalchmai ab Gwyar, and Llecheu ab Arthur, and Rhiwallon with the broom-bush hair; and there was nothing of which they did not know the elements and the material essence."

William of Malmsbury says, that during the reign of William the Conqueror (A.D. 1086) the tomb of Gwalchmai, or Walwen, as he calls him, was discovered on the sea-shore, in a certain province of Wales called Rhôs, which is understood to be that still known by the same name, in the county of Pembroke, where there is a district called in Welsh Castell Gwalchmai, and in English Walwyn's Castle.

In the Graves of the Warriors a similar locality is indicated:--

The grave of Gwalchmai is in Pyton,

Where the ninth wave flows."

The Romances make Gawain one of the four sons of King Lot of Orkney, and of Morgawse, sister to King Arthur; and in them the character for courtesy given to him in the Triads is fully maintained. So proverbial, indeed, was he for this quality, that the highest praise the Squier could bestow upon the address of the Knight who rode the "stede of bras" was,

That Gawain with his olde curtesie,

Though he were come agen out of faerie

Ne coude him not amenden with a word."--line 10410.

20a SATIN ROBE OF HONOUR.--Page 20.

THIS species of honourable dress could only be worn by knights; and, according to Ste. Palaye, was generally the gift of the sovereign, who accompanied it with a palfrey, or, at least, with a horse's bit, either golden or gilded. His words are, "Le manteau long et trainant qui enveloppoit toute la personne, étoit reservé particulièrement au chevalier, comme la plus auguste et la plus noble décoration qu'il pût avoir lorsqu'il n'étoit point paré de ses armes .... on l'appeloit le manteau d'honneur."--(I. 287.)

20b EARL OF RHANGYW.--Page 20.

PROBABLY this is meant for the Earl of Anjou, and was originally written Iarll yr Angyw, the Welsh particle yr, in its contracted form 'r, being by some error of the transcriber incorporated with Angyw, which is the Welsh name for Anjou. What renders this the more likely is, that the Earldom of Anjou, or Angyw, was

according to the Brut, one of the possessions of Arthur, who bestowed it upon his seneschal Sir Kai.

IT would be vain to attempt to find English terms corresponding precisely with those used in the Welsh text, to designate the various kinds of arms which the knights fought with, in this Tale.

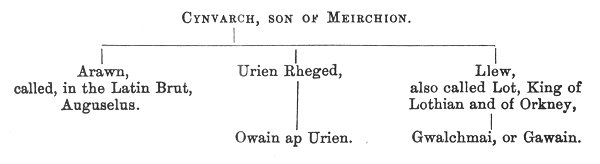

THE following genealogical table will explain this consanguinity, as given in the Welsh Pedigrees.

From very remote periods down to the time of Elizabeth, the Welsh kept up their Pedigrees with much care, and many copies of them are extant both in public and private collections; and although in these occasional discrepancies may be perceived, yet, in general, their authenticity is well established. It must be allowed, that it appears somewhat extraordinary that these family records should be transmitted with such accuracy through so many generations. But when we consider the imperative obligations of the Welsh Laws upon this subject, we are no longer surprised at the existence of such ancient documents, nor at the solicitude of the Welsh to preserve them.

"It has been observed," says the Essayist on Welsh Pedigrees, in the Transactions of the Cymmrodorion Society, "that genealogies were preserved as a matter of necessity, under the ancient British constitution. A man's pedigree was to him of the first importance, as thereby be was enabled to ascertain and prove his birthright, and claim the privileges which the law attached to it. Every one was obliged to show his descent through nine generations, in order to be acknowledged a free native, by which right he claimed his portion of land in the community. He was also affected with respect to legal Process in his collateral affinities through nine degrees; for instance, every murder committed had a fine levied on the relations of the

murderer, divided into nine degrees; his brother paying the greatest, and the ninth in relationship the least. The fine thus levied was in the same proportions distributed among the relations of the victim. A person beyond the ninth descent formed a new family; every family was represented by its elder, and these elders from every family were delegates to the national council."

21b GIVE ME YOUR SWORDS.--Page 21.

THIS modesty, in disclaiming praise, and attaching merit to others, was one of the most esteemed qualities of knighthood. Ste. Palaye quotes from Olivier de la Marche (Mém. i. 315), a contest of generosity somewhat similar to that between Owain and Gwalchmai. "Jacques de Lalain et Piétois, en 1450, ayant fait armes à pied, se renverserent lun sur l'autre; ils furent relevés par les escortes et amenés aux juges qui les firent toucher ensemble en Signe de paix. Comme Lalain, par modestie, voulut envoyer son bracelet, suivant la convention faite pour le prix, Pietois déclara qu'ayant ete aussi bien que lui porté par terre, il se croiroit également obligé de lui donner le sien. Ce nouveau combat de politesse finit par ne plus parler de bracelet, et par former une etroite liaison d'amitié entre ces genereux ennemis."--(I. 150.)

A FEAST which took three years to prepare, and three months to consume, appears in our degenerate days as something quite enormous; but it is a trifle to what we read in another of the Mabinogion, where a party spend eighty years in listening to the songs of the birds of Rhianon, that charm away the remembrance of their sorrows.

21d A DAMSEL ENTERED, UPON A BAY HORSE.--Page 21.

THE custom of riding into a hall, while the Lord and his guests sat at meat, the memory of which is still preserved in the coronation ceremonials of this country, might be illustrated by innumerable passages of ancient Romance and History. But I shall content myself with a quotation from Chaucer's beautiful and half-told Tale of Cambuscan.

And so befell that after the thridde cours

While that this king sit thus in his nobley,

Herking his ministralles hir thinges pley

Beforne him at his bord deliciously, p. 63

In at the halle dore al sodenly

Ther came a knight upon a stede of bras,

And in his hond a brod mirrour of glas;

Upon his thombe he had of gold a ring,

And by his side a naked swerd hanging:

And up be rideth to the highe bord.

In all the halle ne was ther spoke a word,

For mervaille of this knight; him to behold

Ful besily they waiten yong and old."--10,390-10,401.

22a AND ANOINT HIM WITH THIS BALSAM.--Page 22.

THE healing art was always confined to females in chivalric times, a principal part of whose education it formed, and to the -wives and daughters of knights was confided the care of such as were sick or wounded. Of this, the instances are so numerous, that it is needless to adduce any here.

We find, from the English metrical version of this Tale, that the ointment here mentioned, was the gift of Morgant le sage, very probably the same as Morgan le fay, who was sister of King Arthur, and wife to Urien Rheged, and whose skill in magic was justly celebrated, as the adventure of the Manteau mal taillé will unfortunately prove.

23a WRESTED FROM HER BY A YOUNG EARL.--Page 23.

THE name of this invader is in Ywain and Gawin, "The ryche eryl, syr Alers,"--line 1871; and the "Cuens Alers," in the Chevalier au Lion.

24a A BEAUTIFUL BLACK STEED.--Page 24.

THE name of Owain's horse is recorded, with the epithet of "irrestrainable" (Anrheithfarch), but we cannot venture to affirm that the Carn Aflawg (or grasping-hoofed) of the Triads, was either the charger which he received from the Lady of the Castle, or that which met with so disastrous a fate at the falling of the portcullis.

25a WENT ON HIS WAY, AS BEFORE.--Page 25.

THE story of this adventure, as well as that of the fountain, appears to have been popular in the Principality, during the Middle Ages, as it is alluded to in an Ode addressed to Owain Glendower, by

[paragraph continues] Gruffydd Llwyd ab Davydd ab Einion, one of his Bards, about the year 1400.

Of this, the following translation is given in Jones's Welsh Bards, I. 41:--

"On sea, on land, thou still didst brave

The dangerous cliff, and rapid wave;

Like Owain, who subdued the knight,

And the fell dragon put to flight,

Yon moss-grown fount beside;

The grim, black warrior of the flood,

The dragon, gorged with human blood,

The water's scaly pride."

THIS part of the Tale is by no means clearly expressed, but it is evidently intended to be understood that Luned was incarcerated in a stone cell, near which Owain chanced to halt for the night. We subsequently find that he shut up the Lion in the same place, during his contest with Luned's persecutors.

THIS monster is in the English called "Harpyns of Mowntain," and he is, moreover, said to have been "a devil of mekil pryde." According to this and the French version, the good knight (who, it appears, had married a sister of Sir Gawain) was, originally, the, father of "sex knyghts," two of whom Harpyns had already slain, while he threatened to put the remaining four to death, unless their sister was given "hym to wyve." The costume of the Harpyns and the four young men is very characteristic.

"With wreched ragges war thai kled

And fast bunden thus er thai led:

The geant was both large and lang,

And bar a lever of yren ful strang,

Tharwith he bet them bitterly,

Grete rewth it was to her tham cry,

Thai had no thing tham for to hyde.

A dwergh yode on the tother syde;

He bar a scowrge with cordes ten,

Thar-with he bet tha gentil men."

And further on, it is said of the giant,

"Al the armure he was yn

Was noght bot of a bul-skyn."

29a STATE OF STUPOR.--Page 29.

THE literal meaning of this passage is not advantageous to the four-and-twenty ladies, as it gives them a character for anything but sobriety. It is possible, however, that allusion is made to some act of necromancy (not by any means unusual in the old writers of romance), by which they were thrown into a state of insensibility.

SPYTTY.--This term is derived from the Latin word Hospitium, and is used to designate those establishments which were erected and maintained by the monks for the reception of travellers. They bore some remote resemblance to our present inns, and were generally placed in secluded spots at a distance, from any town. Several places in Wales retain the recollection of these hospitable institutions in the name they still bear, as Spytty Ivan, Spytty Cynvyn, &c.

As some explanation of this strange expression, it may, be noticed, that in another of the Mabinogion, called the "Dream of Rhonabwy," Owain is represented as having an army of Ravens in his service, which are engaged in combat with some of Arthur's attendants. But in that, as well as in the present Tale, the adventure is introduced with an abruptness that can only be accounted for by supposing that the story was well known, and that it formed a part of that great store of Romance which existed among the Welsh, and which furnished to the other nations of Europe the earliest materials of imaginative composition. This Raven Army of the Prince of Rheged has evidently a connection with the armorial hearings of that house already alluded to.

33:1 March ap Meirchion, Gwythyr ap Greidiol, and Gwgawn Gleddyfrudd, were three of Arthur's Knights; the second of them was father to Queen Gwenhwyvar.

34:1 In the Life of St. Kentigern, mention is made of a wicked king of Strathclyde, called Morken. Perhaps he is the Morcant, who caused the death of Urien Rheged.

Probably it is through a confusion of names, by no means unusual in those days, that Urien's wife, Morgan le Fay, is by the old romancers accused of an attempt to assassinate him.

35:1 Myv. Arch. i. 105.

35:2 Myv. Arch. i. 78.

35:3 This line, with the substitution of Cambria for Lloegria [England], was taken as the subject of a speech to rouse the Welsh to the due consideration of their literature, by the Rev. Thomas Price of Crickhowel, at the Meeting p. 35 of the Cymreigyddion Society of Abergavenny, in the Autumn of 1835. The effect it produced was quite electric.

36:1 Lancelot du Lac is generally considered as an exception to the general rule, that all the heroes of the Arthurian Romances are of Welsh origin. But it has been suggested to me by a learned Antiquary, that this distinction does not really exist, the name of Lancelot being nothing more than a translation of Paladr-ddellt (splintered spear), which was the name of a knight of Arthur's Court, celebrated in the Triads.

36:2 The arrangement of ancient pedigrees is at all times attended with difficulty, but vain indeed would be the attempt to reconcile the genealogies of Romance with those of history.

In Morte d'Arthur, Owain's Mother is Morgan le Fay, sister to King Arthur.

40:1 Kai's horse, according to the Welsh authorities, was called Gwineu gwddwf hir, the long-necked bay.

41:1 It is somewhat singular that this adventure was undertaken on behalf of Luned, who, under the title of the damoysel saueage, rode to Arthur's Court, to beseech the championship of some of the Knights of the Table rounde, for her' sister dame Lyones, of the Castel peryllous. The story is again referred to in a subsequent Note.

41:2 According to the Romances, Arthur's Queen was daughter of King Leodegrance.

44:1 We trace the customs of a country in what may appear accidental expressions. Thus a cushion in a chair was one of the requisites of a Welsh establishment.

Three things proper for a man to have in his house,--

A virtuous wife,

His cushion in his chair,

And his harp in tune.

In like manner it is particularly mentioned in the present tale, that Arthur had "a cushion of red satin under his elbow," p. 3; and that at the Castle where Kynon was received, on his way to the adventure of the Fountain, the maidens, in doing him honour, " placed cushions both beneath and around him," when he sat down to meat, p. 6. In this latter instance, the cushions we find were covered with red linen.

44:2 Swans appear to have been a great dainty in those days. Of the luxurious Monk in the Pilgrimage to Canterbury, Chaucer tells us, "A fat swan loved he best of any rost."--line 206.

44:3 Uniformity of dress in those who held the same office, appears to be dwelt upon with much satisfaction by the writers of the Middle Ages. In Geoffrey of Monmouth, the thousand young noblemen, who, at Arthur's Coronation Banquet, assisted Kai in serving up the dishes, were clothed like him in robes of Ermine. The same writer proceeds to tell us, that "at that Time Britain was arrived to such a pitch of Grandeur, that whether we respect its Affluence of Riches, Luxury of Ornaments, or Politeness of Inhabitants, it far surpassed all other Kingdoms." And he adds, "The Knights in it that were famous for Feats of Chivalry, wore their Clothes and Arms all of the same colour and Fashion. And the Women also no less celebrated for their Wit, wore all the same Kind of Apparel."--Thompson's Translation.

In the Procession to Canterbury, Chaucer relates that

"An HABERDASHER, and A CARPENTER,

A WEBBE, a DYER, and a TAPISER,

Were alle yclothed in o livere,

Of a solemne and grete fraternite."--line 363.

51:1 See Du Cange, in voce.

52:1 A long note on the story of the Fountain of Barenton in printed separately on p. 67, so which the reader is referred.

A fountain possessed of the like properties occurs in the Fabliau of "The Paradise of Love," and a similar one is mentioned in " The noble Hystory of Kyng Ponthus of Galyce."

53:1 Crug gorseddawl, "the hill of Judicature."--Dr. Pughe's Welsh Dictionary.