Yucatan Before and After the Conquest, by Diego de Landa, tr. William Gates, [1937], at sacred-texts.com

The Yucatecans naturally knew when they had done wrong, and they believed that death, disease and torments would come on them because of evildoing and sin, and thus they had the custom of confessing to their priests when such was the case. In this way, when for sickness or other cause they found themselves in danger of death, they made confession of their sin; if they neglected it, their near relatives or friends reminded them of it; thus they publicly confessed their sins to the priest if he was at hand; or if not, then to their parents, women to their husbands, and the men to their wives.

The sins of which they commonly accused themselves were theft, homicide, of the flesh, and false testimony; in this way they considered themselves in

safety. Many times, after they had recovered, there were difficulties over the disgrace they had caused, between the husband and wife, or with others who had been the cause thereof.

The men confessed their weaknesses, except those committed with their female slaves, since they held it a man's right to do with his own property as he wished. Sins of intention they did not confess, yet considered them as evil, and in their counsels and sermons advised against them.

Those widowed did not marry for a year thereafter, nor know one of the other sex for this tire.; those who infringed this rule were deemed intemperate, and they believed some ill would come on them.

In some of the fasts observed for their fiestas they neither ate meat nor knew their wives. They always fasted when receiving duties in connection with their festivals, and likewise on undertaking duties of the State, which at times lasted as long as three years; those who violated their abstinence were great sinners.

So given were they to their idolatrous practices that in times of necessity even the women and youths and maidens understood it as incumbent on them to burn incense and pray to God that he free them from evil and overcome the demon who was the cause of it.

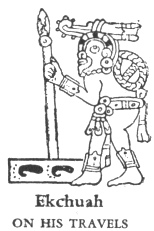

Even travelers on the roads carried incense with them, and a little plate on which to burn it; and then wherever they arrived at night they erected three small stones, putting a little incense on each, and three flat stones in front of these, on which they burned incense, praying to the god they called Ekchuah * that he bring them safely back home; this ceremony they performed every night until their return, unless there were some other who could do this, or even more, on their account.

|

The Yucatecans had a great number of temples, sumptuous in their style; besides these temples in common the chiefs, priests and principal men also had their oratories and idols in their houses for their private offerings and prayers. They held Cozumel and the well at Chichén Itzá in as great veneration as we have in our pilgrimages to Jerusalem and Rome; they visited them to offer gifts, especially at Cozumel, as we do at our holy places; and when they did

not visit they sent offerings. When traveling also, and passing an abandoned temple, it was their custom to enter for prayers and burn incense.

So many idols did they have that their gods did not suffice them, there being no animal or reptile of which they did not make images, and these in the form of their gods and goddesses. They had idols of stone (though few in number), others more numerous of wood, but the greatest number of terra cotta. The idols of wood were especially esteemed and reckoned among their inheritances as objects of great value. They had no metal statues, there being no metals in the country. As regards the images, they knew perfectly that they were made by human hands, perishable, and not divine; but they honored them because of what they represented and the ceremonies that had been performed during their fabrication, especially the wooden ones.

The most idolatrous of them were the priests, the chilánes, the sorcerers, the physicians, the chacs and the nacónes. It was the office of the priests to discourse and teach their sciences, to indicate calamities and the means of remedying them, preaching during the festivals, celebrating the sacrifices and administering their sacraments. The chilánes were charged with giving to all those in the locality the oracles of the demon, and the respect given them was so great that they did not ordinarily leave their houses except borne upon litters carried on the shoulders. The sorcerers and physicians cured by means of bleeding at the part afflicted, casting lots for divination in their work, and other matters. The chacs were four old men, specially elected on occasion to aid the priest in the proper and full celebration of the festivals. There were two of the nacónes; the position of one was permanent and carried little honor, since it was his office to open the breasts of those who were sacrificed; the other was chosen as a general for the wars, who held office for three years, and was held in great honor; he also presided at certain festivals.

46:* The figure in the text, from the Madrid codex, shows the North Star god (so called) in the usual habiliments of Ekchuah, the headbands, corded hamper and pouch, on his travels, also bearing a flint-tipped spear. Ekchuah is the recognized god of the merchants, the

|