Early Discoveries in Crete--How "Tattered Legends" have been "reclothed"--Dramatic Revelations at Knossos--Famous Fresco of the Cup-bearer--Pre-Hellenic Peoples not Barbarians--The Kheftiu of the Egyptian Texts--Phœnicians' Blue Dye came from Crete--Blue Robes of "Lost Atlantis" People--The Throne and Council Chamber of Minos--How Men were judged--Plaster Relief of Sacred Bull--Traces of Earlier Palace--A Visit to the Knossos--"Wooden Walls" of the Island Kingdom--Official, Religious, and Domestic Quarters--Frescoes in Queen's Megaron--Boxing and Dancing in the "Theatral Area"--Drainage Systems of Crete and Sumeria--Phæacians of Homer as the Cretans--Glimpses of Palace Life from the Odyssey--Votive Offerings in Shrines and Caves--How Queen Victoria honoured an Ancient Custom--Sacred Animals and Symbols----Snake Goddess and Priestess--How Cretan Ladies were dressed--Greek and Maltese Crosses--The Star Form of Isis.

"THE ancient history of Crete", it used to be customary to write, "begins with the heroic or fabulous times. Historians and poets tell us of a king called Minos, who lived before the Trojan War. Then comes the well-known story of the Minotaur, Theseus, and Ariadne." The solar symbolists disposed of the various legends as poetic fictions.

The controversy aroused by the discoveries of Schliemann at Mycenæ and Tiryns was being waged with vigour and feeling when a native Cretan excavated at Knossos a few great jars and fragments of pottery of Mycenæan character. The spot was afterwards visited by several archæologists, including Dr. Schliemann and Dr. Dörpfeld, and a preliminary investigation brought to

light undoubted indications that the remains of an ancient palace, partly built of gypsum, lay beneath the accumulated debris of ages. It was impossible, however, to make satisfactory arrangements with the local proprietors or the Turkish Government. The view expressed by Mr. W. J. Stillman, that the ruins were those of the famous Labyrinth, did not attract much attention.

In 1883 some peasants in the eastern part of the island happened upon ancient votive objects in the Dictæan cave, which they had been in the habit of utilizing as a shelter for their goats. These they put on the market, and as there was a great demand for them, a brisk trade in Cretan antiquities sprang up. Archæologists were again drawn to the island, and excavations which did not produce great results were conducted in front of the cave. This made the peasants redouble their efforts to supply a growing demand, and as they met with much success the archæologists became more and more impressed by the possibilities of the island as an area for conducting important research work. In 1894 Sir Arthur Evans and Mr. Hogarth paid a visit to Crete, and examined both the site of Knossos and the Dictæan cave. The times were inauspicious for their mission, for the island was seething with revolt against the Turkish authorities. Sir Arthur, however, was able to effect the purchase of part of the Knossos ground, having become convinced that great discoveries remained to be made. What interested him most at the time were the indications afforded by mysterious signs on blocks of gypsum of a system of hitherto unknown prehistoric writing. It was not, however, until 1900 that he was able to acquire by purchase the entire site of Knossos and conduct excavations on an extensive scale.

During the interval, further investigations were conducted

by different archæologists at the Dictæan cave, which is double-chambered. Inscribed tablets and other finds came to light, but all research work had to be abandoned in 1897, when it was found that the upper cave was blocked with fallen rock. The political unrest on the island, besides, made it unsafe for foreigners to pursue even the peaceful occupation of digging for ancient pottery and figurines of bronze and lead.

In 1900, however, Sir Arthur Evans operating at Knossos, and Mr. Hogarth at the Dictæan cave, achieved results which more than fulfilled their most sanguine hopes. What they accomplished was to reveal traces of an ancient and high civilization, of which the Mycenæan appeared to be an offshoot. No such important discovery had been made since Schliemann, twenty-five years previously, unearthed the graves he so confidently believed to be those of Agamemnon and his companions. "Here again", as Mr. Asquith said at the annual meeting of the subscribers to the British School at Athens, 1 "scepticism received an ugly blow. Legends", he added, "which had become somewhat ragged and tattered have been decently reclothed. The mountain on which Zeus was supposed to have rested from his labours, and the palace in which Minos invented the science of jurisprudence, are being brought out of the region of myth into the domain of possible reality."

Sir Arthur Evans went to Crete as a trained and experienced archæologist, and was assisted from the beginning, in March, 1900, by Dr. Duncan Mackenzie, who had already distinguished himself by his excavations on the island of Melos, and Mr. Fyfe, the British School of Athens architect. A large staff of workers was employed, and by the time the season's work was concluded

in June a considerable portion of the Knossos palace was laid bare.

Among the most remarkable finds were the wall paintings that decorated the plastered walls of the palace corridors and apartments. These did more to arouse public interest in pre-Hellenic civilization than even the burnt city of Troy or the gold masks of kings in the graves at Mycenæ. Here were wonderful pictures of ancient life vividly portrayed, of highly civilized Europeans who were contemporaries of the early Biblical Pharaohs, and lived in splendour and luxury long centuries before Solomon employed the skilled artisans of Phœnicia to decorate his temple and palace. And what manner of people were they? Not rude barbarians awaiting the dawn of Hellenic civilization, but men and women with refined faces and graceful forms, whose costumes resembled neither those of the Egyptians, Greeks, nor Romans. There was a note of modernity in this antique and realistic art and the manners of life it portrayed. The ladies with their puffed sleeves, narrow waists, and flounced skirts, might well have walked, not from a Cretan palace, but some Paris salon of the 'eighties and 'nineties.

In his first popular account of his excavations, Sir Arthur Evans gave a vivid description of his dramatic discovery of the fresco named the "cup-bearer".

"The colours", he wrote, "were almost as brilliant as when laid down over three thousand years before. For the first time the true portraiture of a man of this mysterious Mycenæan race rises before us. There was something very impressive in this vision of brilliant youth and of male beauty, recalled after so long an interval to our upper air from what had been till yesterday a forgotten world. Even our untutored Cretan workmen felt the spell and fascination.

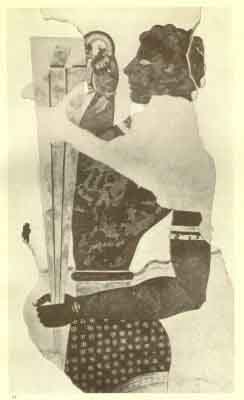

THE CUP-BEARER, KNOSSOS

From a photograph kindly lent by Sir Arthur Evans

They, indeed, regarded the discovery of such a painting in the bosom of the earth as nothing less than miraculous, and saw in it the 'icon' of a saint! The removal of the fresco required a delicate and laborious process of under-plastering, which necessitated its being watched at night, and old Manolis, one of the most trustworthy of our gang, was told off for the purpose. Somehow or other he fell asleep, but the wrathful saint appeared to him in a dream. Waking with a start, he was conscious of a mysterious presence; the animals round began to low and neigh, and there were visions about; 'φαντάξει {Greek fantáksei}', he said, in summing up his experiences next morning, 'The whole place spooks!' 1

This life-sized figure of a youth remains in a wonderful state of preservation from the thighs upwards, and is a feature of Candia museum. He carries in front a long pointed vessel, adorned with silver and gold, with "wine foam" at the brim, one raised hand grasping the handle and the other clutching it at the tapering end. His face is finely depicted in profile, the well-proportioned features are quite modern, and he is clean-shaved; the forehead is ample, the eyes dark, and the hair black and curly. Sir Arthur Evans thinks the skull is of "brachycephalic" (broad-headed) type; others regard it as "mesacephalic" (medium). Round the neck is a necklace of silver, and there is an car-ring in the only ear shown, which appears to be mounted with a blue stone. There is an armlet on the upper part of the right arm, and a bracelet with what appears to be a seal round the left wrist, which looks just like the "wristlet-watch" worn at the present day. The body is well developed, and the waist tightened by a girdle. He wears a closely-fitting loin-cloth, which is richly embroidered.

Before the famous figure was reached, the excavators had laid bare a paved corridor nearly 4 yards wide. The left wall retained traces of plaster which had been decorated with a continuous fresco of a procession of male and female dignitaries. None of the faces, however, survived. It was noted that the figures resembled closely those of the "Keftiu" depicted in Egyptian tombs.

An interesting feature of these and other frescoes was the evidence they afforded of the use of a blue dye among the Cretans. Some male figures wore bright-blue robes, and others white robes bordered with blue. Apparently the Phœnicians were not the first to utilize the famous dyes which have long been so closely associated with them. Proofs were subsequently forthcoming to place this belief beyond doubt. Long before the Phœnicians supplanted the Cretans as sea-traders the islanders produced bright-blue garments, which were worn, it would appear, on special ceremonial occasions. It is of interest to note in this connection that the inhabitants of Plato's Atlantis had a similar custom. After the bull was sacrificed, and the sacred cup deposited in the temple of the gods, and "the fire round the sacrifice had been cooled, all of them dressed themselves in beautiful dark-blue robes . . . and then mutually judged one another as respects any accusations of transgressing the laws. After the acts of judgment were over, when day came, they inscribed their decisions on a golden tablet, and deposited them as memorials, together with their dresses." 1

A hoard of inscribed clay tablets was discovered by Evans in a bath-shaped terra-cotta receptacle within a small chamber. These were embedded in charcoal, indicating that they had been placed in a wooden box which at some period was destroyed by fire.

As the work of excavation made progress, many remarkable discoveries were made in that first season which appealed to the imaginations of scientists and workers alike. The glimpses of life afforded by fragmentary frescoes set the ghosts of vanished Cretans walking once again; the wind rustling through the disinterred ruins by night seemed "like light footfalls of spirits" passing up and down the stately corridors; the past "out of her deep heart spoke". By day

There streamed a sunlight vapour, like the standard

Of some ætherial host;

Whilst from all the coast

Louder and louder, gathering round, there wandered

Over the oracular woods and divine sea

Prophesyings which grew articulate.

The prophesyings of the excavators were no vain dreams; with dramatic swiftness they were revealed almost as soon as they were conceived. Confidently search was made for tangible evidence that this palace had been occupied by the legendary Minos, or one of the kings who bore that name or title, when his very council chamber was unearthed, and the most ancient throne in Europe brought to light.

In the heart of the palace this priceless relic of an antique civilization had lain buried in debris all through the ages that saw the coming and going of Homer's heroes, the rise and fall of Assyria, the fading beauty of Babylon, the flickering loveliness of Egypt, Persian splendour, the glory of Greece and the grandeur of Rome. The kings that sat in it had long faded into the region of myth and fancy; it was believed by wise scholars that they never existed at all. And here was the royal throne to tell another story!

The "Throne Room" was situated between the upper part of the spacious central court of the palace and the "long gallery" of the western wing. It was entered, however, from the court alone. Those who sought the presence of the king had first to pass through a small ante-room about seven yards square, the rubble walls of which, the excavators found, had been plastered with day and faced with stucco made beautiful by artists who were skilled draughtsmen and brilliant colourists.

Stone benches were ranged round the walls of the council chamber, and between two of these on the north side stood the gypsum throne of the king on a raised slab. Here sat the Minos surrounded by his high officers of state. There is seating accommodation for about twenty on the benches.

The throne, which was found intact, is of graceful form. It presents an interesting contrast to that on which the statue of the Egyptian King Kafra of Pyramid fame is seated. Its back, which is higher and less severe. has an undulating outline, and resembles somewhat an oak leaf. The base broadens downward from the seat, which is hollowed to fit the body comfortably, and the sides are gracefully carved, the "double moulded arch" in front resembling "late Gothic" designs.

To this chamber may have been led such a wanderer as brave Ulysses, who desired to accelerate his return to his native home. He would have found the grave Minos enthroned amidst his councillors, who sat "side by side on polished stones", and perhaps heard him sneak like the Phæacian king in the Odyssey:--

Chiefs and Senators! I speak

The dictates of my mind, therefore attend.

This guest, unknown to me, hath, wand'ring found

My palace, either from the East arrived.p. 123

Or from some nation on our western side.

Safe conduct home he asks, and our consent

Here wishes ratified, whose quick return

Be it our part, as usual, to promote;

For at no time the stranger, from what coast

Soe'er, who hath resorted to our doors,

Hath long complained of his detention here.

Haste--draw ye down into the sacred Deep

A vessel of prime speed, and, from among

The people, fifty and two youths select,

Approved the best; then, lashing fast the oars,

Leave her, that at my palace ye may make

Short feast, for which myself will all provide.

Thus I enjoin the crew, but as for these

Of sceptred rank, I bid them all alike

To my own board, that here we may regale

The stranger nobly, and let none refuse.

Call, too, Demodocus, the bard divine,

To share my banquet, whom the gods have blest

With pow'rs of song delectable, unmatch'd

By any, when his genius once is fired. 1

Opposite the "high seat" of Minos in the "Throne Room" was a shallow tank with stone breastwork. Its use is uncertain. The theory that ambassadors and others washed here while awaiting the king is not convincing; there were bath-rooms elsewhere in the vast palace in which travel-wearied men could refresh and cleanse themselves. Perhaps it was simply part of the decorative scheme. Fish may have been kept here to give a touch of realism to the scenes painted on the stucco-plastered walls. Traces survive of a riverside fresco, with reeds and grasses and budding flowers beside flowing waters, which must have imparted to the chamber an air of repose. On either side of the door were two gleaming griffins, crested with peacock's plumes, "showing", says Sir Arthur Evans,

"that this Indian fowl was known to the East Mediterranean world long before the days of Solomon". A flowery landscape formed a strangely-contrasting background, with ferns and palm-trees fringing the soft blue stream.

Before this chamber was swept by the fire which destroyed the palace, it must have been at once stately and beautiful. No doubt the benches were strewn with richly-embroidered rugs and cushions to complete the brilliant colour scheme of which fragmentary traces survive. The throne appears to have been richly decorated. "The whole face of the gypsum", writes Sir Arthur Evans, "had been coated with a fine white plaster wash, and this again coloured in various ways. The seat showed distinct remains of a brilliant red colour. A minute examination of the back disclosed the fact that fine lines had been traced on it such as are also visible on the wall frescoes, a technical device, borrowed from Egyptian practice, for guiding the artist's hands. It would appear, therefore, that the back of the throne had been once decorated with an elaborate colour design." 1 The paved floor was also, apparently, set in a border of gypsum covered with plaster and richly adorned.

Another interesting early find was the "wine cellar" of the palace--or rather the "cellars". In the lengthy corridors were found intact rows of great jars from which wine was drawn by the "cup-bearers" for the feast, and oil was likewise stored. Worthy of special mention is also the painted plaster relief of a bull which dignified the wall of one of the chambers. "It is life-sized, or somewhat over", its discoverer wrote at the time. "The eye has an extraordinary prominence, its pupil is yellow and the iris a bright-red, of which narrower bands again

PAINTED PLASTER RELIEF--BULL'S HEAD--KNOSSOS

From a photograph kindly lent by Sir Arthur Evans

appear encircling the white towards the lower circumference of the ball. The horn is of greyish hue. . . . Such as it is, this painted relief is the most magnificent monument of Mycenæan plastic art that has come down to our time. The rendering of the bull, for which the artists of this period showed so great a predilection, is full of life and spirit. It combines in a high degree naturalism with grandeur, and it is no exaggeration to say that no figure of a bull at once so powerful and so true was produced by later classical art." 1

The first season's discoveries made it evident that the palace had been of great dimensions and splendour. Nothing was found to indicate that it flourished after the Mycenæan period. It had evidently been destroyed by fire in pre-Hellenic times, before the thirteenth century B.C. Traces were also found of a still earlier palace, below which were the layers of the Neolithic (Late Stone Age) period. Regretfully Sir Arthur Evans had to suspend operations in June 1900 on such a promising site, owing to the malarious conditions and distressing dust-clouds raised by the south wind from Libya. Nine brief weeks, however, had revealed enough to satisfy even so fortunate an archæologist as Sir Arthur, who had the luck of Schliemann combined happily with richer experience and technical skill. No doubt could any longer remain that a great pre-Homeric civilization had flourished in Crete, and that Minos had been rescued from the fairyland of the solar symbolists to take his place once again among the mighty monarchs of the great days of old.

Were it possible for us, by waving the wand of a magician, to conjure before our eyes this wonderful palace, as it existed when Queen Hatshepsut reigned over Egypt and Thothmes III was fretting to seize the reins of

power, we should be first of all impressed by the modernity of its aspect.

We are guided from the sea-shore, like the hero of the Odyssey, who visited the dwelling of Alcinous, the Phæacian king, by a goddess in human guise. At a favourable point of vantage on the poplar-fringed highway, we are afforded the first glimpse of the palace of Knossos. It is situated beside a river 1 on a low hill in the midst of a fertile valley, about 3½ miles from Candia. The dominating feature of the landscape is sacred Mount Juktas, with its notched peak. It seems as if the "hammer god" had intended to shape the mountain like an Egyptian pyramid, and, having finished one side, abandoned the task soon after beginning to splinter out the other.

The palace, which is approached by paved roadways, has a flat roof and forms a rough square, each side being about 130 yards long. No walls surround it. Crete, like "old England", is protected by its navy--its "wooden walls". The Minos kings have suppressed the island pirates who were wont to fall upon unprotected towns and plunder them, and hold command of the sea. 2

We enter the palace by the north gate, passing groups of soldiers on sentry duty. A comparatively small force could defend the narrow way between the massive walls which lead us to the great Central Court. Note these little towers and guard-houses, from which they could discharge their arrows against raiders. There are dark dungeons beneath us, over 20 feet deep, in which prisoners are fretting their lives away, thinking of "Fatherland, of child, and wife, and slave", and "the wandering fields of barren foam" on which they had ventured to defy the might of Minos.

The Central Court in the middle of the palace is over 60 yards long and about 30 yards wide. On the eastern side are the private apartments of the royal family, but these are not entered from the Court, but along mazy corridors which are elsewhere approached. The first door on the western side leads us through an ante-room to the Throne Room. Farther down, and near the centre of the Court, is the shrine of the Snake goddess. Behind it are the west and east Pillar Rooms and the room containing temple repositories; these apartments appear to have a religious significance. Farther south is the large "Court of the Altar". We pass out of the Court at the northern end, and penetrate the western wing of the palace. We find it is divided about the middle by the "Long Gallery". Walking southward, we pass, on the right, numerous store rooms, until we reach an entrance leading to the sacred apartments behind the shrine of the Snake goddess. It has already dawned upon us that we are in a labyrinthine building, if not the real Labyrinth with its intricate and tortuous passages through which the famous Theseus was able to wander freely and extricate himself from with the aid of the clue given to him by the princess Ariadne. One apartment leads to another, and when our progress is arrested by blind alleys we turn back and find it difficult, without the help of a guide, to return to the Long Gallery that opens on the zigzag route back to the Central Court. The eastern wing is similarly of mazy character. In the southern part of it are reception rooms, living-rooms, bedrooms, and bath-rooms. These include the "Hall of the Colonnades", the "Hall of the Double Axes", the "Queen's Megaron", and the "Room of the Plaster Couch". 1 Stairways lead to the upper stories.

The rooms assigned to the ladies are approached

through a dark "dog's-leg corridor". We enter the "Queen's Megaron" and are silenced by its wonderful beauty. The paved floor is overlaid with embroidered rugs, and has a richly-coloured "surround" of painted plaster. Frescoes adorn the walls. Here is a woodland scene with a brilliantly-plumaged bird in flight. On the north, side is the whirling figure of a bright-eyed dancing girl, her long hair floating out on either side in rippling bird-wing curves, her arms responding to the rise and fall of the music. She leans slightly forward, poised on one foot. She wears a yellow jacket with short arms, with a zigzag border of red and blue. Other dancers are tripping near her. Beyond these are the musicians. 1 We are reminded of one of the scenes on the famous shield of Achilles:--

There, too, the skilful artist's hand had wrought,

With curious workmanship, a mazy dance,

Like that which Daedalus in Knossos erst

At fair-hair'd 2 Ariadne's bidding framed.

There, laying on each other's wrist their hand,

Bright youths and many suitor'd maidens danced:

In fair white linen these; in tunics those

Well woven, shining soft with fragrant oils . . .

Now whirl'd they round with nimble practised feet,

Easy, as when a potter, seated, turns

A wheel, new fashioned by his skilful hand,

And spins it round, to prove if true it run:

Now featly mov'd in well-beseeming ranks.

A numerous crowd, around, the lovely dance

Survey'd, delighted. 3

Another fresco is a picturesque study of sub-marine life. Fish dart to and fro above the ocean floor about

two great snouted dolphins, the air bubbles darting from their fins and tails to indicate that they are in motion. 1

In the Queen's Megaton the Cretan ladies are wont to chatter over their needlework during the heat of the day. They admire the works of art on the walls, and discuss the merits of the various draughtsmen who reside elsewhere in the palace. Note how little furniture they require. They won't have anything that is not absolutely necessary in their rooms, and what they have is beautiful. The charm of wide spaces appeals to them. A broad fresco must not be interrupted by ornaments that might distract attention from such a masterpiece. It is sufficient in itself to fill a large part of the room.

Visitors who arrive dusty and weary are conducted to the bath-room, which is entered through a door at the north-west corner. Its walls are plainly painted, but relieved from the commonplace by a broad dado of flowing spirals with rosette centres. Portable tubs are provided, and attendants spray water over those who use them.

We pass from this, the south-eastern, to the northeastern wing, and find it is occupied by artistic craftsmen who are continually employed in beautifying the palace. Art is under royal patronage. Here, too, are the rooms of musicians. Farther on are the butlers; these provide the stores for the cooks, who occupy the domestic quarters south of the Queen's Megaton and beneath it.

Once again the guards permit us to walk along the corridor of the north entrance, and we turn from their guard-houses and sentinel-boxes to visit the "Theatral Area" at the north-western corner of the palace. On

two sides are tiers of stone steps on which spectators seat themselves. One is the royal "grand stand", and it has accommodation for about 200 people; the other is reserved for young people. The crowds stand round about in a circle behind the wooden barriers. Sometimes the attraction is an athletic display. Boxers and wrestlers are popular. Here, too, the dancers display their skill when the king calls upon them to "tread the circus with harmonious steps." Their dances have a religious significance.

Turning southward from the Theatral Area we walk along the broad west court outside the palace. It is paved and terraced. Almost the whole of this outer portion of the western wing is occupied by stores, and the court is the market-place. Here come the traders who sell their fruit and vegetables and wares; and here too those who pay their taxes in kind. Officials and merchants pass to and fro; here is a great consignment of goods from Egypt which is being unpacked. The scribes are busy checking invoices, and issuing orders for its disposal. A group of young people gather round a sailor, who is accompanied by a native Egyptian, and fills their ears with wonderful stories regarding the river Nile and the great cities on its banks.

Our steps are directed to the southern side of the palace. Here is the door leading to the "Court of the Altar" and other sacred rooms. Farther on is the "Court of the Sanctuary" in the southern part of the east wing. Workmen are busy near us extending the palace beyond the royal apartments.

We have now taken a rapid survey of the great square palace of Knossos. There are many details, however, that have escaped our notice. The Cretans were not only great builders, but also experienced sanitary engineers.

A GLIMPSE OF THE EXCAVATED REMAINS OF THE PALACE OF KNOSSOS

An excellent drainage system was one of the remarkable features of the palace. Terra-cotta drain-pipes, which might have been made yesterday, connect water-flushed closets "of almost modern type", and bath-rooms with a great square drain which workmen could enter to effect repairs through "manholes". Rain water was introduced into the palace, and its flow automatically controlled.

Crete, however, was not alone in anticipating modern sanitary methods. Long before the Late Minoan period, which began about 1700 B.C., the Sumero-Babylonians had a drainage system. Drains and culverts have been excavated at Nippur in stratum which dates before the reign of Sargon I (c. 2650 B.C.), as well as at Surghul, near Lagash, Fara, the site of Shuruppak, and elsewhere. It is uncertain, however, whether the Cretans derived their elaborate drainage system from Sumeria. What remains clear, however, is that on the island kingdom, and in cities of the Tigro-Euphratean valley, the problem of how to prevent the spread of water-borne diseases had been dealt with on scientific lines.

A glimpse of such a palace as that of Knossos, if not of this palace itself, is obtained in the Odyssey, and in that part from which quotation has been made in dealing with the "Throne Room".

Ulysses (Odysseus), the wanderer, is cast ashore on the island of Scheria, the seat of the Phæacians, "who of old, upon a time, dwelt in spacious Hypereia". Dr. Drerup 1 and Professor Burrows 2 have independently arrived at the conclusion that Scheria is Crete, Hypereia being Sicily, "and that the origin of the Odyssey is to be sought for in Crete". Burrows adds: "It can be at once granted that attention has been unduly concentrated on Ithaca, Leukias, and Corcyra, while the numerous references

in the Odyssey 1 to the topography of Crete have been neglected". Dr. Drerup draws attention to a most suggestive passage in the seventh book, in which the secret is "let out." The Phæacian King, Alcinous, promises that his seamen will convey the shipwrecked stranger to his home, "even though it be much farther than Euboea, which", he explains, "certain of our men say is the farthest of lands, they who saw it, when they carried Rhadamanthus of the fair hair, to visit Tityos, son of Gaia". 2 Now Rhadamanthus was the brother of the Cretan King Minos. "What was he doing in Corcyra?" asks Professor Burrows. "The Phæacians," adds the same writer, "themselves mariners, artists, feasters, dancers, are surely the Minoans of Crete."

Ulysses (Odysseus) is found on the sea-coast by the princess Nausicaa. She provides him with clothing and food, and says--

Up stranger! seek the city. I will lead

Thy steps towards my royal father's house

Where all Phæacia's nobles thou shalt see.

Her proposal is to lead him to her father's farm, where he will gaze on the safe harbour in which

Our gallant barks

Line all the road, each stationed in her place,

And where, adjoining close the splendid fane

Of Neptune, 3 stands the forum with huge stones

From quarries hither drawn, constructed strong,

In which the rigging of their barks they keep

Sail cloth and cordage, and make smooth their oars.

She intends to leave him at this point, fearing that the sailors might ask, "Who is this that goes with Nausicaa?

and cast imputations on her character. Apparently the gossips were as troublesome in those times as in our own. She adds naively:

I should blame

A virgin guilty of such conduct much,

Myself, who reckless of her parent's will

Should so familiar with a man consort,

Ere celebration of her spousal rites.

The princess then advises the wanderer to make his way from the royal home farm to the palace:--

Ask where Alcinous dwells, my valiant sire.

Well known is his abode, so that with ease

A child might lead thee to it.

When he is received within the court he should at once seek the queen, her mother.

She beside a column sits

In the hearth's blaze, twirling her fleecy threads

Tinged with sea purple, bright, magnificent!

With all her maidens orderly behind.

If he makes direct appeal to this royal lady he will be sure to "win a glad return to his island home".

The wanderer is much impressed by the gorgeous palace of the Phæacian king, towards which he is led by the grey-eyed goddess Athene, who assumed the guise of a girl carrying a pitcher. He pauses on the threshold, gazing with wonder on the inner walls covered with brass and surrounded by a blue dado. Doors are of gold and the door-posts of silver. He has a glimpse of a feasting chamber; the seats against the wall are covered with mantles of "subtlest warp", the "work of many a female hand". There the Phæacians are wont to sit eating and drinking in the flare of the torches held in the hands of golden figures of young men.

Fifty handmaidens attend on the King and Queen. Some grind the golden corn in millstones. Others sit spinning and weaving with fingers

Restless as leaves

Of lofty poplars fluttering in the breeze.

So closely do they weave linen that oil will fall off it. just as the Phæacian men are skilled beyond others as mariners, so are the women the most accomplished at the loom. The goddess Athene has given them much wisdom as workers, and richest fancy.

Outside the courtyard of the palace is a large garden surrounded by a hedge. There grows many a luxuriant and lofty tree.

Pomegranate, pear, the apple blushing bright,

The honied fig, and unctuous olive smooth.

Those fruits, nor winter's cold nor summer's heat

Fear ever, fail not, wither not, but hang

Perennial . . .

Pears after pears to full dimensions swell,

Figs follow figs, grapes clust'ring grow again.

Where clusters grew, and (every apple stript)

The boughs soon tempt the gath'rer as before.

There too, well-rooted, and of fruit profuse,

His vineyard grows . . .

On the garden's verge extreme

Flow'rs of all hues smile all the year, arranged

With neatest art judicious, and amid

The lovely scene two fountains welling forth,

One visits, into every part diffus'd

The garden ground, the other soft beneath

The threshold steals into the palace court,

Whence ev'ry citizen his vase supplies.

The wanderer, having gazed with wonder about him, enters the palace. He sees men pouring out wine to keen-eyed Hermes, the slayer of Argos, before retiring

for the night. Athene again comes to his aid, and wraps him in a mist so that he passes, unseen by anyone, until he reaches the queen. He tells her of his plight, and asks for safe conduct to his native land, and the great lady takes pity on him. The wanderer is given food and wine. Before he retires to rest he relates to King Alcinous how he was cast on the island shore and conducted to the farm by the princess. Recognizing that the girl has compromised herself, his majesty offers her in marriage to the stranger, promising

House would I give thee and possessions too

Were such thy choice.

He adds, however, that if he prefers to return home no man in Phæacia "shall by force detain thee". The wanderer's decision is, "Grant to me to visit my native shores again". So the matter ends. Odysseus is conducted to

a fleecy couch

Under the portico, with purple rugs

Resplendent, and with arras spread beneath

And over all with cloaks of shaggy pile.

The king and queen retire to an "inner chamber".

Next morning the king and his counsellors assemble as indicated in the description of the Throne Room of Knossos palace, and arrangements are completed to give Odysseus a safe conduct home. Before he goes a feast is held, at which "the beloved minstrel", Demodocus, sings of the Trojan war. Then a visit is paid to the "Theatral Area", where athletes display feats of strength. A young man challenges the stranger boastfully. Roused to wrath by his speech, Odysseus says:

I am not, as thou sayest,

A novice in these sports but took the lead p. 136

In all, while youth and strength were on my side.

But I am now in bands of sorrow held,

And of misfortune, having much endured

In war, and buffeting the boist'rous waves.

He, however, flung a quoit and broke all records. Then he challenged the young man who taunted him

To box, to wrestle with me, or to run . . .

There is no game athletic in the use

Of all mankind, too difficult for me.

The challenge is not accepted, however. Then the king says:

We boast not much the boxer's skill, nor yet

The wrestler's; but light-footed in the race

Are we, and navigators well informed.

Our pleasures are the feast, the harp, the dance

Garments for change, the tepid bath, the bed.

Come, ye Phæacians, beyond others skilled

To tread the circus with harmonious steps,

Come play before us; that our guest arrived

In his own country, may inform his friends

How far in seamanship we all excel,

In running, in the dance, and in the song. 1

In these passages we probably have, as some authorities think, real Cretan memories. It is uncertain whether or not actual Cretan poems were utilized in the Odyssey. Professor Burrows suggests that the glories of the palace of Alcinous "were sung by men who had heard of them as living realities, even if they had not themselves seen them; men who had walked the palaces (Knossos and Phæstos) perhaps, if not as their masters, at least as mercenaries or freebooters". 2

It will be noted that Alcinous says the Phæacians do

not boast much of the skill of their boxers. Yet the Cretan pugilists are found depicted in seal impressions, on vases, &c., suggesting that they were regarded with pride as peerless exponents of the "manly sport". It may be, however, that in the last period (Late Minoan III) the island boxers were surpassed by those among the more muscular northerners, who were settled in Crete in increasing numbers. "Late Minoan III", writes Professor Burrows, "is a long period, and marks the successive stages of a gradually decaying culture." The "Cretan memories" in the Homeric poems "refer to Late Minoan III". 1 Apparently the islanders were still famous as skilled mariners, while their dancing was much admired; but as athletes and warriors they had to acknowledge the superiority of the less cultured invaders who had descended on their shores.

Reference has been made to the sacred rooms in the great palace of Knossos. Unlike the Egyptians, the Cretans erected no temples. Their religious ceremonies were conducted in their homes, on their fields, and beside sacred mountain caves. Sir Arthur Evans discovered in the south-eastern part of the palace, near the ladies' rooms, a little shrine which could not have accommodated more than a few persons.

Another shrine was entered from the Central Court to the south of the Throne Room in the western wing. It would appear that this part of the palace was invested with special sanctity. In one of the apartments were found superficial cists in the pavement. The first two had been rifled. Then an undisturbed one was located and opened. It contained a large number of what appeared to be deposits of religious character--vessels containing burnt corn which had been offered to a deity or

to deities, tablets, libation tables, and so on. Fragments of faience (native porcelain) had figures of goddesses, cows and calves, goats and kids, and floral and other designs. A number of cockles and other sea-shells artificially tinted in various colours also came to light. Apparently these cists answered the same purpose as sacred caves in which religious offerings were placed.

This custom of effecting a ceremonial connection with a holy place still survives in our own country. Portions of clothing are attached to trees overhanging wishing and curative wells. and coins and pins are also dropped into them. "Pin wells", sometimes called "Penny wells", are not uncommon. In some cases nails are driven into the tree. Special mention may be made of the well and tree of Isle Maree, on Loch Maree, in the Scottish county of Ross and Cromarty. It was visited on a Sunday in September, 1877, by the late Queen Victoria. Her Majesty read a short sermon to her gillies, and afterwards, with a smile, attached an offering to the wishing tree. Such offerings are never removed, for it is believed that a terrible misfortune would befall the individual who committed such an act of desecration. In ancient Egypt offerings were made at tombs, and in Babylonia votive figures of deities mounted on nails were driven into sacred shrines.

Seal impressions, which have been found in the Cretan palace cists, are of special interest. Among the designs were figures of owls, doves, ducks, goats, dogs, lions seizing prey, horned sheep, gods and goddesses. Flowers, sea-shells, houses, &c., were also depicted. One clay impression of a boxer suggests that it was deposited by the pugilist himself to ensure his good luck at a great competition in the Theatral Area. The shells suggest that sailors desired protection. One seal of undoubted

A CRETAN SHRINE: RESTORED BY SIR ARTHUR EVANS

Snake Goddesses, or goddesses and priestess, "fetish cross", shells, libation jugs, stones hollowed for holding offerings, &c.

maritime significance shows a man in a boat attacking a dog-headed sea-monster. The floral seals were probably offerings to the earth mother in Spring. No doubt the cow suckling its calf and the goat its kid were fertility symbols.

The faience relief of the wild goat and its young is one of the triumphs of Cretan art. It is of pale-green colour, with dark sepia markings. The animals are as lifelike as those depicted in the Palæolithic cave-drawings. One of the kids is sucking in crouched posture, and the other bleats impatiently in front. The nimble-footed mother has passed with erect head and widely-opened eyes. She is the watchful protector and constant nourisher of her young--a symbol of maternity. The cow and calf is also a fine composition. Commenting on these, Sir Arthur Evans says that "in beauty of modelling and in living interest, Egyptian, Phœnician, and, it must be added, classical Greek . . . are far surpassed by the Minoan artist".

Among the marine subjects in faience is one showing two flying fish (the "sea swallows" of the modern Greeks) swimming between rocks and over sea-shells lying on the sand.

Nothing, however, among these votive deposits can surpass in living interest the faience figures of the Snake goddess and her priestess. The former is a semi-anthropomorphic figure with the ears of a cow or some other animal. The exaggerated ear suggests "Broad Ear", one of the members of the family of the Sumerian sea-god Ea. She may have been thus depicted to remind her worshippers that she was ever ready to hear their petitions. On the other hand, it is not improbable that she had at one time the head of a cow or sow. Demeter at Phigalia was horse-headed, and there were serpents in her hair.

[paragraph continues] This goddess of Crete has a high head-dress of spiral pattern, round which a serpent has enfolded itself, and apparently its head, which is missing, protruded in front like the uræus on the Egyptian "helmets" of royalty. Another snake is grasped by the head in her right hand and by the tail in the left, and its body lies wriggling along her outstretched arms, and over her shoulders, forming a loop behind, which narrows at her waist and widens out below it. Other two snakes are twined round her hips below the waist. These reptiles are of green colour with purple-brown spots. Evidently they are symbols of fertility and growth of vegetation. The goddess is attired in a bell-shaped skirt suspended from her "wasp waist", and a short-sleeved, tight-fitting jacket bodice, with short sleeves, open in front to display her ample breasts. Her skin is white, her eyes dark: she wears a necklace round her neck, and her hair falls down behind but only to her shoulders, being gathered up in a fringed arrangement at the back of the head.

The priestess, or votary, has her arms lifted in the Egyptian attitude of adoration. In each hand she grasps a small wriggling snake. A stiff girdle entwines her narrow waist. Unfortunately the head is missing. The jacket bodice is similar to that of the goddess, and the breasts are also ample and bare. "The skirt", writes Lady Evans, "consists of seven flounces fastened apparently on a 'foundation', so that the hem of each flounce falls just over the head of the one below it. . . . Over this skirt is worn a double apron or 'polonaise' similar to that of the goddess, but not falling so deeply, and not so richly ornamented. The main surface is covered with a reticulated pattern, each reticulation being filled with horizontal lines in its upper half. The general effect is that of a check or small plaid. . . . The whole costume

of both figures seems to consist of garments carefully sewn and fitted to the shape without any trace of flowing draperies. 1

Among the symbols, which had evidently a religious significance, are the "horns of consecration", the sacred pillars and trees, the double axe, the "swastika" (crux gammata), a square cross with staff handles, and the plain equal-limbed cross. These are represented on seals, in faience, and on stones. Sir Arthur Evans suggests that a small marble cross he discovered--he calls it a "fetish cross"--occupied a central position in the Cretan shrine of the mother goddess. "A cross of orthodox Greek shape", he says, "was not only a religious symbol of Minoan cult, but seems to be traceable in later offshoots of the Minoan religion from Gaza to Eryx". He adds: "It must, moreover, be borne in mind that the equal-limbed eastern cross retains the symbolic form of the primitive star sign, as we see it attached to the service of the Minoan divinities. . . . The cross as a symbol or amulet was also known among the Babylonians and Assyrians. It appears on cylinders (according to Professor Sayce, of the Kassite period), apparently as a sign of divinity. As an amulet on Assyrian necklaces it is seen associated, as on the Palaikastro (Crete) mould, with a rayed (solar) and a semi-lunar emblem--in other words it once more represents a star." The Maltese cross first appears on Elamite pottery of the Neolithic Age: it was introduced into Babylonia at a later period. In Egypt it figures prominently n the famous floret coronet of a Middle Kingdom princess which was found at Dashur, and is believed by some authorities to be of Hittite origin.

If the Cretan cross was an astral symbol, it would appear that the snake or dove goddess was associated, like

the Egyptian Isis and the Babylonian Ishtar, with Sirius or some other star which was connected with the food supply. The rising of Sirius in Egypt coincides with the beginning of the Mile flood. It appears on the "night of the drop". The star form of the bereaved Isis lets fall the first tear for Osiris, and as the body moisture of deities has fertilizing and creative properties, it causes the river to increase in volume so that the land may be rendered capable of bearing abundant crops. Osiris springs up in season as the rejuvenated corn spirit.

Other sites in Crete will be dealt with in the chapters which follow. But before dealing with these in detail, it will be of interest to glean evidence from the general finds regarding the early stages of civilization on the island and the first peoples who settled there, and also to compare the beliefs that obtained among the various peoples of the ancient race who, having adopted the agricultural mode of life, laid the foundations of great civilizations, among which that of Crete was so brilliant an example.

7:1 London, 30th October, 1900.

119:1 Monthly Review, March, 1901, p. 124.

120:1 The Critias, Sec. XV

123:1 Cowper's Odyssey, VIII, 30-54.

124:1 The Annual of the British School at Athens, Vol. VI, p. 38.

125:1 Annual of the British School at Athens, Vol. VI, pp. 52-3.

126:1 The river used to flow nearer the palace site than it does at present.

126:2 Thucydides, I, 2-4.

127:1 These and other names were given to the apartments by Sir Arthur Evans.

128:1 Only one dancing figure has survived of this fresco.

128:2 Or "Ariadne of the lovely tresses".

128:3 Iliad, XVIII, 590 et seq. (Derby's translation).

129:1 These dolphins resemble closely the so-called "swimming elephants" on Scottish sculptured stones. Like the doves they had evidently a religious significance. Pausanias tells of a Demeter which held in one hand a dolphin and in another a dove.

131:1 Homer (1903), pp. 130 et seq.

131:2 The Discoveries in Crete (1907), pp. 207 et seq.

132:1 III, 291-300; XIX, 172-9, 188-9, 200, 338.

132:2 Butcher and Lang's Odyssey, p. 113.

132:3 Poseidon in the original.

136:1 Extracts from the Odyssey, Books VII and VIII (Cowper's translation).

136:2 The Discoveries in Crete, p. 209.

137:1 The Discoveries in Crete, pp. 209-10.

141:1 The Annual of the British School at Athens, Vol. IX, pp. 74 et seq.