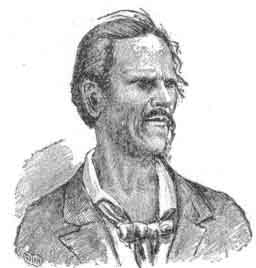

FIG. 2. KAITAE, NEAREST DESCENDANT OF THE LAST KING OF EASTER ISLAND.

The population of Easter Island is not stated in actual figures by any of the traditions or legends, but all agree in the statement that the different districts were peopled by numerous and powerful clans who were constantly at war with each other. The immense amount of work performed by the image-makers and platform builders would indicate the employment of a great many persons, if accomplished within a reasonable limit of time, or the extension over several centuries, if the undertaking was carried out by successive generations. The ruins of extensive settlements near Tahai Bay Kotatake plains, around Puka Manga-Manga mountain, the Rana-Hana-Kana coast, the vicinity of Anakena, the shores of La Pérouse Bay, and extending along the coast from Tongariki to Vinapu in an almost unbroken line, would prove either the presence of numerous inhabitants, or a frequent change of location. The limited area of the 32 square miles of surface available for cultivation precludes the idea of any very dense population, and many reasons might be assigned for a frequent change of habitation. We know that the stone houses at Orango were only occupied daring the feast of "bird eggs." The image-builders engaged in the quarries of Rana Roraka probably lived at Tongariki, and entire communities may have changed location at different seasons of the year from failure of water supply, or some equally sufficient reason.

The early Spanish voyagers estimated the population at between 2,000 and 3,000. Admiral Roggeveen states that he was surrounded by several thousand natives before he opened fire upon them. Captain Cook, fifty-two years later, placed the number at between 600 and 700, and Foster, who was with him, estimated them at 900. Twelve years later (1786) La Pérouse placed the population at 2,000. Bushey (1825) puts the number at about 1,500. Kotzebue and Lisiansky make more liberal estimates. Equally chimerical and irreconcilable deductions are made by recent writers. Mr. A. A. Salmon, after many years' residence on the island, estimates the population between 1850 and 1860 at nearly 20,000. The diminution of the actual number of inhabitants progressed rapidly from 1863, when the majority of the able-bodied men were kidnaped by the Peruvians, and carried away to work in the guano deposits of the Chincha Islands, and plantations in Peru. Only

few of these unfortunates were released, and all but two of them died upon the return voyage, from small-pox. The disease was introduced on the shore and nearly decimated the island in a short time. An old man called Pakomeo is at, present the only survivor of those returned from slavery, and he is eloquent in the description of the barbarous treatment received from the hands of the Peruvians. In 1864 a Jesuit mission was established on the island, and through the teachings of Frère Eugene, the ancient customs and mode of life were replaced by habits of more civilized practice.

H. M. S. Topaze visited the island in 1868. At that time the population was about 900, one-third of the number being females. In 1875 about 500 persons were removed to Tahiti under contract to work in the sugar plantations of that island. In 1878 the mission station was abandoned, and about 300 people followed the missionaries to the Gambier Archipelago.

Mr. Salmon took a complete census of the people just before the arrival of the Mohican, and we were furnished with a list containing the names of every man, woman, and child on the island. The total number of natives is at present 155. Of these 68 are men, 43 women, 17 boys under fifteen years of age, and 27 girls of corresponding age. The population has been for several years at a standstill, the births and deaths being about equal in numbers. The longevity of the islanders appears to compare favorably with the natives of more favored lands. The oldest man among them is a chief called Mati; his actual age is not known, but he must be upwards of ninety, and his wife is nearly of the same age.

The last king was kidnaped by the Peruvians and died in captivity, but his nearest descendant is a sturdy old fellow (Fig. 2) called Kaitae,

FIG. 2. KAITAE, NEAREST DESCENDANT OF THE LAST KING OF EASTER ISLAND.

about eighty years of age. The simple mode of life, frugal diet, freedom from care and anxiety, with regular habits, are favorable to the longevity of the race.