THIS is Yaqui belief.

A great bird lived on the hill of Otam Kawi. Every morning he would fly out in search of food. He caught men, women and little children and carried them back to Otam Kawi to eat. In those days the people always were watchful. They couldn't have fiestas because when they had pascolas, always two or three of the people were carried away by the big bird. The Yaquis lived in hu'ukis, little houses made of mud and branches that looked like the house of a pack-rat, because they were afraid of the great bird.

There was an old man who earned his livelihood by hunting deer. He did nothing else. He had only one daughter. She was big with a child

who was soon to be born, when the bird carried away her husband. The old hunter, his wife and the daughter only remained, and the daughter pregnant. The baby came in the afternoon.

It was a man child that the girl had. And the old grandfather continued hunting deer.

About a year later the grandmother went out early one morning to bring in water. The bird came by and carried her away. So the grandfather and the girl went on bringing up the child.

The next year the bird carried away the mother, and the grandfather brought the child up on cow's milk. There were cows in those days, but no animals of the claw.

When the little boy was old enough to walk, he went everywhere with his grandfather. He walked all over the monte hunting. This little boy never grew very big. When he was ten, he was still very small.

One afternoon he was seated outside of the house and he said, "I have no mother."

"Ah," said the grandfather, "The big bird carried her away. First he took your father, then your grandmother, then your mother."

"Where is that bird? I am going to grow up and kill that bird."

The old man laughed.

When the boy was older, his grandfather made him a bow and some arrows, and every day he went out practicing. He became very strong. But he was still small. When he was fifteen years old, he measured no more than three and a half feet in stature. He went everywhere with the old deer-hunter, his grandfather.

One day the boy said, "I am going to hunt out

that bird. I am angry." When he was still not full-grown, he went about alone, walking through the monte and looking up into the sky.

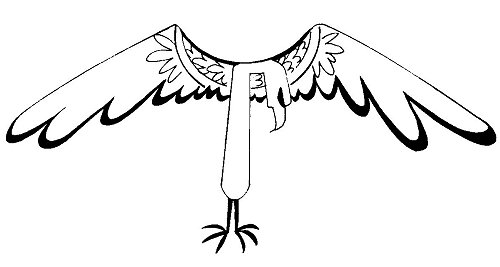

There is a level plain east of Potam called maretabo'oka'apo. There the little boy walked. He had been hunting for three days. He carried many arrows in his quiver of javelina hide. Then he saw the bird. Quickly he jumped into a hole. The big bird sat down in a mesquite tree, waiting for him to come out of the hole. The boy stayed there all day long, watching the big bird in the mesquite tree. He saw everything; the size, the colors of the feathers, the big eyes, and all. At night he went farther back in the hole and fell asleep. Late at night he awoke. The bird had gone with the coming of night.

Three days later, the boy returned to his home, very late. His grandfather was not there. The boy carried two dark sticks on which he had placed many pitahayas. He hung them near the door where his grandfather would enter. The boy was inside cooking deer meat when the old man returned and saw the pitahayas.

As he entered he asked, "My son, where have you been?"

"Over in the hills."

"Weren't you afraid of the big bird?"

The little boy said, "I saw him. I saw all of his colored feathers and his big eyes. I climbed into a hole. I return only to ask permission to kill the bird. This bow would never kill him. It is too little. I wish you would make me one of that wood called kunwo. And I need another kind of arrow, made of wo'i baka. I will go as soon as you make me these."

"But you are so little. That bird will kill you," said the old man.

Many Yaquis lived in the neighborhood and they all came over that night to talk. They asked the little boy if he had really seen the big bird.

"Yes, I saw it. It has feathers of many colors, a big body, and long claws. I am going to make a lot of little animals out of that bird."

"This boy is crazy," said an old man. And many of the elders believed that he was. "But we'll see," said these older men. And they went back to their homes.

The old grandfather then made three kinds of pinol. The little boy had asked him to. He made pinol of corn, of wheat, and of garbanzas. When the little boy had this and his bow and arrows, he said, "Call the people together."

All of the people gathered, kobanaom, soldiers, women and children. Everybody came, from all of the eight pueblos. They said, "Are you the boy who is going to kill the big bird?"

"Are you the man?" laughed a kobanao.

"Yes," said the little boy.

Then an old man who lived near to Otam Kawi spoke. "Wait for this bird near Otam Kawi. He lives there. He only goes away to catch the people. He always comes back there. You will see there a great pile of bones."

The people bade the boy good-by that night, and he said to his grandfather, "Now I know I can kill that bird. I will be back in three days."

Everybody was content. "If you kill him, we can have pascolas again!"

The next day, before dawn, the boy and the grandfather left. At dawn, they saw the bird

fly over. But they were safe below the mesquite trees. They walked through the monte toward Otam Kawi. "No farther than this," said the boy, Leave me here. I'm going to find out where the big bird roosts."

All day long the boy waited. At last he saw the bird come in and alight in a large tree. Night fell and the bird went to sleep. Then the boy softly approached the tree. There, he knelt and prayed for a long time. Then he began to measure. He measured twenty-five feet from the foot of the mesquite tree toward the west. There he made a deep hole, ten feet deep. When dawn came, he was still hunting poles and branches with which to cover it.

The bird saw him and was angry. The boy went down into the hole. He prepared his bow well. The bird came down from the mesquite tree and went to the cave. The boy was inside, looking out. He shot the big bird in the eye with an arrow.

The bird flew to the top of the mesquite tree. The boy shot three more arrows. The bird fell.

For a long time the boy did not come out of the cave. He waited to be sure that the bird was dead. When he was sure, he came out and went over to the big dead bird.

He pulled out a handful of its feathers and threw them into the air and the feathers became owls. With another handful of feathers he made smaller owls. With four handfuls of feathers, he made four classes of owls.

In the same way, with other handfuls of feathers, he made birds of every kind, crows and roadrunners. He threw the feathers and they became birds of different colors.

When he had finished all of the feathers, he

cut off a piece of meat from the dead bird. He threw this and it became a mountain lion. He cut another piece and made another kind of lion, which is a little braver. With another he made the topol, and with another, a spotted cat. Thus, the boy made four classes of big cats. After that he made four smaller kinds of cats.

With more meat the boy made foxes and racoons and also four types of coyotes. He made snakes and all kinds of animals that have claws.

When all of the meat was gone, only bones remained. He dragged the bones under the mesquite tree and started home. He arrived there in two days. He came in very happily, dressed in a suit of feathers he had made from the bird, and he wore four feathers in his hat, two on either side.

He entered and his grandfather was frightened to see him covered with blood from the meat of the animal.

The old man was afraid, and he said, "What happened to you?"

"I killed the big bird. Now you may walk about the world."

The old man rushed out of the house. He talked with his neighbors who ran to advise those in other pueblos, and the people of those pueblos spread the news to others.

People came from all the eight pueblos. They still walked at night as before, because they didn't believe the big bird was dead. The governor came, and when all of the people were gathered the old men talked. "You really did kill it?" they asked.

"Yes, sirs. I made many little animals out of the feathers and the meat. I made owls of four kinds. I made four kinds of coyotes, four kinds

of small cats, four kinds of lions, all animals of the claw."

"Well, let us see if this is true. We will send men from each pueblo, from Potam, from Vicam, from Torim, from Bacum, from Cocorit, Rajum, Juirivis and Belen to see the proof."

"The bones are there," said the little boy. "If they aren't you may cut my neck." And he led off on horseback. They all arrived and the boy showed them the hole he had dug. "From here I shot and hit him in the eye."

Along the road the people saw many animals, and little birds flying. The boy talked to the people, saying "These little birds don't do any harm to us. But those animals I made from the meat of the big bird, you must take care about those. From today on they are not going to be gentle. We no longer have danger from above. Now we must take care from below. These animals aren't much good for food, only for clothing. The birds are valuable only for their pretty feathers."

The men and the soldiers saw the bones of the big bird, and they went away contented, and in every pueblo began to make great fiestas. MT

The Papago and Pima Indians tell of the slaying of a man-eating eagle which has some aspects in common with this myth (Densmore 1929: 45-54). The Cochiti also have a story about a cannibal eagle (Benedict 1931: 211).