Click to enlarge

When the Storm God Rides, by Florence Stratton, collected by Bessie M. Reid [1936], at sacred-texts.com

Why did old Quanah, the blanket weaver known among all the Indians of the southwest country, give so much time and care to a blanket which he had not finished after many years of work? The Indians of his tribe asked this question, but old Quanah always smiled and shook his head. Some day, he said, he would tell them.

Quanah, who had spent many years in the making of blankets, knew better than any other Indian how to put into them the beauty of color and form. He had once been a brave warrior, a fighter who took pride in his use of bow and arrow, and in following the trails of animals

and enemies of the tribe. But when at last a poisoned arrow struck him in the leg and caused him to be crippled, he had to stay in camp and could no longer fight. Quanah, the proud fighter, did not like this. He did not like staying at home with the women of the tribe.

Because Quanah refused to be idle he at last began to make blankets, and because he was a man who took pride in his work he learned the art of making blankets with great care. Through forest and swamp he went seeking strange herbs, roots and flowers with which to make dyes that other blanket weavers had never used. He found out what were the best fleeces and fibers to use in making blankets smooth and warm and

strong. He always made his own dyes with great care. He wove his blankets each time with different patterns, so that no two were alike. And he worked so carefully that he became known everywhere for his blankets.

Indian chiefs of other tribes heard of him and came to see him at work or to buy blankets from him. Other blanket makers came from many miles away to watch him make his dyes and weave the colored fleeces into his lovely designs. Quanah gladly tried to show them what he knew, but when they had gone away and tried to do as he had told them they found that they could not. They did not have Quanah's art, his magic touch.

For years Quanah worked. His blankets

became famous. Some looked like the rosy clouds and mists of dawn. Others had the vivid colors of the red and yellow prairie flowers. Each one he made seemed to be better than the one before.

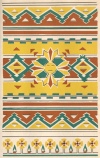

But there was one blanket which Quanah worked on year after year without finishing. Each day he would work a little bit on it, but slowly it grew until the Indians could see that in its center there would be a great golden, shining sun. Quanah was very careful in making the dyes for this blanket and weaving colors slowly into place. Around the bright sun other colors of sunset were woven. The red and purple of evening clouds were there, and also the yellow

hues of thin clouds that were close to the golden sun. The Indians kept asking him what he was going to do with this wonderful blanket, but Quanah always smiled and said he would tell them when it was finished. Years went by. Quanah kept working, until he was so old that his fingers shook when he worked.

At last one day the Indians found the old blanket maker lying on a mat with his wrinkled face turned up to the skies. He was dying. But beside him lay the wonderful blanket, finished. Its many shades seemed to change as the Indians took it carefully in their fingers. The sun in its middle burned with the brightness of the real sun in the sky, and all the gleaming colors around it seemed to flow

like the waters of the river when the changing lights of sunset struck them. As the Indians held this lovely blanket they looked down at old Quanah and saw that he was dying. Then they began to wail or to beat their breasts, because they knew they would never have another blanket maker like him.

But Quanah slowly opened his eyes and whispered to them: "My blanket is finished at last. Now I will tell you why I have made it with so much care and have put so much beauty into it. It is for the most worthy of our tribe. The man who has done most for his people is to have this blanket, so that our children may know that it is a fine thing for them to become good members of our

tribe." And with this old Quanah's voice failed and he died.

Soon the Indians began to ask one another who should have the blanket. Who had done the most for his tribe? The chief called a council to decide the question. One man who was a brave warrior was pointed out as the right man. Another who was a great hunter of game was named. But the Indians could not agree about it. Some wanted this man; others wanted that one.

At length the chief held up his hand for silence. "We have forgotten the man who has really done most for us," said the chief pointing towards the still body of old Quanah lying before the tribal altar. "There he lies. Quanah himself

should have the blanket. Is he not famous everywhere? Did he not make our tribe known far and wide?"

"Yes, Quanah must have the blanket!" cried the Indians. No longer did they argue. The old man who had made it was the very one who should have it, for he had done most for them. They did not like to see the lovely blanket laid away in the earth from all eyes, but they tenderly wrapped Quanah's body in its folds and then laid the old man and his finest work in the ground. Then each member of the tribe placed upon the new grave a large stone. At last they went away. They were sad because Quanah had died and because they could see the blanket no more.

But they were to see something as wonderful as the blanket. The spirit of Quanah, wishing them to have something of the beauty which they had buried with the blanket, gave its colors back to them in the form of a new kind of flower that began to grow among the stones on the grave. In these flowers were the same reds and yellows and browns which were woven into the blanket. There were the same hues of sunset in the flower petals. They were the same colors which white men later found in these flowers. White men now call them wild gaillardia, or blanket flowers, or fire wheels. Thus it happened that old Quanah gave a new flower to the world.