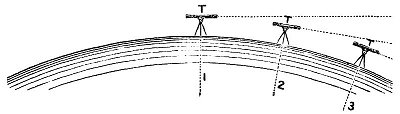

FIG. 9.

On several occasions the six miles of water in the old Bedford Canal have been surveyed by the so-called "forward" process of levelling, which consisted in simply taking a sight of, say 20 chains, or 440 yards, noting the point observed, moving the instrument forward to that point, and taking a second observation; again moving the instrument forward, again observing 20 chains in advance, and so on throughout the whole distance. By this process, without making allowance for convexity, the surface of the water was found to be perfectly horizontal. But when the result was made known to several surveyors, it was contended "that when the theodolite is levelled, it is placed at right angles to the earth's radius--the line of sight from it being a tangent; and that when it is removed 20 chains forward, and again 'levelled,' it becomes a second and different tangent; and that indeed every new position is really a fresh tangent--as shown in the diagram, fig. 9, T 1, T 2, and T 3, representing

the theodolite levelled at three different positions, and therefore square to the radii 1, 2, 3. Hence, levelling forward in this way, although making no allowance for rotundity, the rotundity or allowance for it is involved in the process." This is a very ingenious and plausible argument, by which the visible contradiction between the theory of rotundity and the results of practical levelling is explained; and many excellent mathematicians

and geodesists have been deceived by it. Logically, however, it will be seen that it is not a proof of rotundity; it is only an explanation or reconciliation of results with the supposition of rotundity, but does not prove it to exist. The following modification was therefore adopted by the author, in order that convexity, if it existed, might be demonstrated. A theodolite

was placed at the point A, in fig. 10, and levelled; it was then directed over the flag-staff B to the cross-staff C--the instrument A, the flag-staff B, and the cross-staff C, having exactly the same altitude. The theodolite was then advanced to B, the flag-staff to C, and the cross-staff to D, which was thus secured .as a continuation of one and the same line of sight A, B, C, prolonged to D, the altitude of D being the same as that of A, B, and C. The theodolite was again moved forward to the position C, the flag-staff to D, and the cross-staff to the point E--the line of sight to which was thus again secured as a prolongation of A, B, C, D, to E. The process was repeated to F, and onwards by 20 chain lengths to the end of six miles of the canal, .and parallel with it. By thus having an object between the theodolite and the cross-staff, which object in its turn becomes a test or guide by which the same line of sight is continued throughout the whole length surveyed, the argument or explanation which is dependent upon the supposition of rotundity, and that each position of the theodolite is a different tangent, is completely destroyed. The result of this peculiar or modified survey, which has been several times repeated, was that the line of sight and

the surface of the water ran parallel to each other; and as the. line of sight was, in this instance, a right line, the surface of the water for six miles was demonstrably horizontal.

This mode of forward levelling is so very exact and satisfactory, that the following further illustration may be given with

advantage. In fig. 11, let A, B, C, represent the first position, respectively of the theodolite, flag-staff, and cross-staff; B, C, D, the second position; C, D, E, the third position; and D, E, F, the fourth; similarly repeated throughout the whole distance surveyed.

The remarks thus made in reference to simple "forward" levelling, apply with equal force to what is called by surveyors the "back-and-fore-sight" process, which consists in reading backwards a distance equal to the distance read forwards. This plan is adopted to obviate the necessity for calculating, or allowing for the earth's supposed convexity. It applies, however, just the same in practice, whether the base or datum line is horizontal or convex; but as it has been proved to be the former, it is evident that "back-and-fore-sight" levelling is a waste of time and skill, and altogether unnecessary. Forward

levelling over intervening test or guide staves, as explained by the diagram, fig. 11, is far superior to any of the ordinary methods, and has the great advantage of being purely practical§ and not involving any theoretical considerations. Its adoption along the banks of any canal, or lake, or standing water of any kind, or even along the shore of any open sea, will demonstrate to the fullest satisfaction of any practical surveyor that the surface of all water is horizontal.