Click to enlarge

Fig. 1

Concerning the Waters of the Primitive Earth: What the state of the Regions of the Air was then, and how all Waters proceeded from them; how the Rivers arose, what was their course, and how they ended. Several things in Sacred Writ that confirm this Hydrography of the first Earth; especially the Origin of the Rainbow.

HAVING thus far clear’d our way to Paradise, and given a rational account of its general properties; before we proceed to discourse of the place of it, there is one affair of moment, concerning this Primitive Earth, that must first be stated and explain’d; and that is, How it was water’d; from what causes, and in what manner. How could Fountains rise, or Rivers flow in an Earth of that Form and Nature? We have shut up the Sea with thick walls on every side, and taken away all communication that could be ’twixt it and the external Earth; and we have remov’d all the Hills and the Mountains where the Springs use to rise, and whence the Rivers descend to water the face of the ground: And lastly, we have left no issue for these Rivers, no Ocean to receive them, nor any other place to disburden themselves into: So that our New-found World is like to be a dry and barren Wilderness, and so far from being Paradisiacal, that it would scarce be habitable.

I confess there was nothing in this whole Theory that gave so rude a stop to my thoughts, as this part of it, concerning the Rivers of the first Earth; how they rise, how they flow’d, and how they ended. It seem’d at first, that we had wip’d away at once the Notion and whole Doctrine of Rivers; we had turn’d the Earth so smooth, that there was not an Hill or rising for the head of a Spring, nor any fall or descent for the course of a River: Besides, I had suckt in the common opinion of Philosophers, That all Rivers rise from the Sea, and return to it again; and both those passages, I see, were stopt up in that Earth. This gave me occasion to reflect upon the modern, and more solid opinion, concerning the Origin of Fountains and Rivers, That they rise chiefly from Rains and melted Snows, and not from the Sea alone; and as soon as I had undeceiv’d my self in that particular, I see it was necessary to consider, and examine, how the Rains fell in that first Earth, to understand what the state of their Waters and Rivers would be.

And I had no sooner appli’d my self to that Inquiry, but I easily discover’d, that the Order of Nature in the Regions of the Air, would be then very different from what it is now, and the Meteorology of that World was of another sort from that of the present. The Air was always calm and equal, there could be no violent Meteors there, nor any that proceeded from extremity of Cold; as Ice, Snow or Hail; nor Thunder neither; for the Clouds could not be of a quality and consistency fit for such an effect, either by falling one upon another, or by their disruption. And as for Winds, they could not be either impetuous or irregular in that Earth; seeing there were neither Mountains nor any other inequalities to obstruct the course of the Vapours; nor any unequal Seasons, or unequal action of the Sun, nor any contrary and strugling motions of the Air: Nature was then a stranger to all those disorders. But as for watery Meteors, or those that rise from watery Vapours more immediately, as Dews and Rains, there could not

but be plenty of these, in some part or other of that Earth; for the action of the Sun in raising Vapours, was very strong and very constant, and the Earth was at first moist and soft, and according as it grew more dry, the Rays of the Sun would pierce more deep into it, and reach at length the great Abysse which lay underneath, and was an unexhausted storehouse of new Vapours. But, ’tis true, the same heat which extracted these Vapours so copiously, would also hinder them from condensing into Clouds or Rain, in the warmer parts of the Earth; and there being no Mountains at that time, nor contrary Winds, nor any such causes to stop them or compress them, we must consider which way they would tend, and what their course would be, and whether they would any where meet with causes capable to change or condense them; for upon this, ’tis manifest, would depend the Meteors of that Air, and the Waters of that Earth.

And as the heat of the Sun was chiefly towards the middle parts of the Earth, so the copious Vapours rais’d there were most rarified and agitated; and being once in the open Air, their course would be that way, where they found least resistance to their motion; and that would certainly be towards the Poles, and the colder Regions of the Earth. For East and West they would meet with as warm an Air, and Vapours as much agitated as themselves, which therefore would not yield to their progress that way; but towards the North and the South, they would find a more easie passage, the Cold of those parts attracting them, as we call it, that is, making way to their motion and dilatation without much resistance, as Mountains and Cold places usually draw Vapours from the warmer. So as the regular and constant course of the Vapours of that Earth, which were rais’d chiefly about the Æquinoctial and middle parts of it, would be towards the extream parts of it, or towards the Poles.

And in consequence of this, when these Vapours were arriv’d in those cooler Climats, and cooler parts of the Air, they would be condens’d into Rain; for wanting there the cause of their agitation, namely the heat of the Sun, their motion would soon begin to languish, and they would fall closer to one another in the form of Water. For the difference betwixt Vapours and Water is only gradual, and consists in this, that Vapours are in a flying motion, separate and distant each from another; but the parts of Water are in a creeping motion, close to one another, like a swarm of Bees, when they are setled; as Vapours resemble the same Bees in the Air before they settle together. Now there is nothing puts these Vapours upon the wing, or keeps them so, but a strong agitation by Heat; and when that fails, as it must do in all colder places and Regions, they necessarily return to Water again. Accordingly therefore we must suppose they would soon, after they reacht these cold Regions, be condens’d, and fall down in a continual Rain or Dew upon those parts of the Earth. I say a continual Rain; for seeing the action of the Sun, which rais’d the Vapours, was (at that time) always the same, and the state of the Air always alike, nor any cross Winds, nor any thing else that could hinder the course of the Vapours towards the Poles, nor their condensation when arriv’d there; ’tis manifest there would be a constant Source or store-house of Waters in those parts of the Air, and in those parts of the Earth.

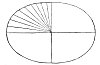

And this, I think, was the establisht order of Nature in that World, this was the state of the Ante-diluvian Heavens and Earth; all their Waters came from above, and that with a constant supply and circulation; for when the croud of Vapours, rais’d about the middle parts of the Earth, found vent and issue this way towards the Poles, the passage being once open’d, and the Chanel made, the Current would be still continued without intermission; and as they were dissolv’d and spent there, they would suck in more and more of those which followed, and came in fresh streams from the hotter Climates. Aristotle, I remember, in his Meteors, speaking of the course of the Vapours, saith, there is a River in the Air, constantly flowing betwixt the Heavens and the Earth, made by the ascending and descending Vapours; This was more remarkably true in the Primitive Earth, where the state of Nature was more constant and regular; there was indeed an uninterrupted flood of Vapours rising in one Region of the Earth, and flowing to another, and there continually distilling in Dews and Rain, which made this Aereal River. As may be easily apprehended from this Scheme of the Earth and Air.

Click to enlarge

Fig. 1

Thus we have found a Source for Waters in the first Earth, which had no communication with the Sea; and a Source that would never fail, neither diminish or overflow, but feed the Earth with an equal supply throughout all the parts of the year. But there is a second difficulty that appears at the end of this, How these Waters would flow upon the even surface of the Earth, or form themselves into Rivers; there being no descent or declivity for their course. There were no Hills, nor Mountains, nor high Lands in the first Earth, and if these Rains fell in the Frigid Zones, or towards the Poles, there they would stand, in Lakes and Pools, having no descent one way more than another; and so the rest of the Earth would be no better for them. This, I confess, appear’d as great a difficulty as the former, and would be unanswerable, for ought I know, if that first Earth had been exactly Spherical; but we noted before, that it was Oval or Oblong; and in such a Figure, ’tis manifest, the Polar parts are higher than the Æquinoctial, that is, more remote from the Center, as appears to the eye in this Scheme. This affords us a present remedy, and sets us free of the second difficulty; for by this means the Waters which fell about the extream parts of the Earth, would have a continual descent towards the middle parts of it; this Figure gives them motion and distribution; and many Rivers and Rivulets would flow from those Mother-Lakes to refresh the face of the Earth, bending their course still towards the middle parts of it.

Click to enlarge

Fig. 2

’Tis true, these derivations of the Waters at first would be very irregular and diffuse, till the Chanels were a little worn and hollowed; and though that Earth was smooth and uniform, yet ’tis impossible upon an inclining surface, but that Waters should find a way of creeping downwards, as we see upon a smooth Table, or a flagg’d Pavement, if there be the least inclination, Water will flow from the higher to the lower parts of it, either directly, or winding to and fro: So the smoothness of that Earth would be no hinderance to the course of the Rivers, provided there was a general declivity in the site and libration of it, as ’tis plain there was from the Poles towards the Æquator. The Current indeed would be easie and gentle all along, and if it chanc’d in some places to rest or be stopt, it

would spread it self into a pleasant Lake, till by fresh supplies it had rais’d its Waters so high, as to overflow and break loose again; then it would pursue its way, with many other Rivers its companions, through all the temperate Climates, as far as the Torrid Zone.

But you'll say, when they were got thither, what would become of them then? How would they end or finish their course? This is the third difficulty, concerning the ending of the Rivers in that Earth; what issue could they have when they were come to the middle parts of it, whither, it seems, they all tended. There was no Sea to lose themselves in, as our Rivers do; nor any Subterraneous passages to throw themselves into; how would they die, what would be their fate at last? I answer, The greater Rivers, when they were come towards those parts of the Earth, would be divided into many branches, or a multitude of Rivulets; and those would be partly exhal’d by the heat of the Sun, and partly drunk up by the dry and sandy Earth. But how and in what manner this came to pass, requires a little further Explication.

We must therefore observe in the first place, that those Rivers as they drew nearer to the Æquinoctial parts, would find a less declivity or descent of ground than in the beginning or former part of their course; that is evident from the Oval Figure of the Earth, for near the middle parts of an Oval, the Semidiameters, as I may call them, are very little shorter one than another; and for this reason the Rivers, when they were advanc’d towards the middle parts of the Earth, would begin to flow more slowly, and by that weakness of their Current, suffer themselves easily to be divided and distracted into several lesser streams and Rivulets; or else, having no force to wear a Chanel, would lie shallow upon the ground like a plash of Water; and in both cases their Waters would be much more expos’d to the action of the Sun, than if they had kept together in a deeper Chanel, as they were before.

Secondly, we must observe, that seeing these Waters could not reach to the middle of the Torrid Zone, for want of descent; that part of the Earth having the Sun always perpendicular over it, and being refresht by no Rivers, would become extreamly dry and parch’d, and be converted at length into a kind of sandy Desart; so as all the Waters that were carried thus far, and were not exhal’d and consum’d by the Sun, would be suckt up, as in a Spunge, by these Sands of the Torrid Zone. This was the common Grave wherein the Rivers of the first Earth were buried; and this is nothing but what happens still in several parts of the present Earth, especially in Africk, where many Rivers never flow into the Sea, but expire after the same manner as these did, drunk up by the Sun and the Sands. And one arm of Euphrates dies, as I remember, amongst the Sands of Arabia, after the manner of the Rivers of the first Earth.

Thus we have conquer’d the greatest difficulty, in my apprehension, in this whole Theory, To find out the state of the Rivers in the Primitive and Antediluvian Earth, their Origin, course, and period. We have been forc’d to win our ground by Inches, and have divided the difficulty into parts, that we might encounter them single with more ease. The Rivers of that Earth, you see, were in most respects different, and in some contrary to ours; and if you could turn

Click to enlarge

Fig. 3

our Rivers backwards, to run from the Sea towards their Fountain-heads, they would more resemble the course of those Ante-diluvian Rivers; for they were greatest at their first setting out, and the Current afterwards, when it was more weak, and the Chanel more shallow, was divided into many branches, and little Rivers; like the Arteries in our Body, that carry the Bloud, they are greatest at first, and the further they go from the Heart, their Source, the less they grow and divide into a multitude of little branches, which lose themselves insensibly in the habit of the flesh, as these little Floods did in the Sands of the Earth.

Because it pleaseth more, and makes a greater impression upon us, to see things represented to the Eye, than to read their description in words, we have ventur’d to give a model of the Primæval Earth, with its Zones or greater Climates, and the general order and tracts of its Rivers: Not that we believe things to have been in the very same form as here exhibited, but this may serve as a general Idea of that Earth, which may be wrought into more exactness, according as we are able to enlarge or correct our thoughts hereafter. And as the Zones here represented resemble the Belts or Fasciæ of Jupiter, so we suppose them to proceed from like causes, that Planet being, according to our judgment, in an Antediluvian state, as the Earth we here represent. As for the Polar parts in that

our Earth, I can say very little of them, they would make a Scene by themselves, and a very particular one; The Sun would be perpetually in their Horizon, which makes me think the Rains would not fall so much there as in the other parts of the Frigid Zones, where accordingly we have made their chief seat and receptacle. That they flow’d from thence in such a like manner as is here represented, we have already prov’d; And sometimes in their passage swelling into Lakes, and towards the end of their course parting into several streams and branches, they would water those parts of the Earth like a Garden.

We have before compar’d the branchings of these Rivers towards the end of their course to the ramifications of the Arteries in the Body, when they are far from the Heart near the extream parts; and some, it may be, looking upon this Scheme, would carry the comparison further, and suppose, that as in the Body the Bloud is not lost in the habit of the flesh, but strain’d thorough it, and taken up again by the little branches of the Veins; so in that Earth the Waters were not lost in those Sands of the Torrid Zone, but strain’d or percolated thorough them, and receiv’d into the Chanels of the other Hemisphere. This indeed would in some measure answer the Notion which several of the Ancient Fathers make use of, that the Rivers of Paradise were trajected out of the other Hemisphere into this, by Subterraneous passages. But, I confess, I could never see it possible, how such a trajection could be made, nor how they could have any motion, being arriv’d in another Hemisphere; and therefore I am apt to believe, that doctrine amongst the Ancients arose from an intanglement in their principles; They suppos’d generally, that Paradise was in the other Hemisphere, as we shall have occasion to show hereafter; and yet they believ’d that Tigris, Euphrates, Nile, and Ganges were the Rivers of Paradise, or came out of it; and these two opinions they could not reconcile, or make out, but by supposing that these four Rivers had their Fountain-heads in the other Hemisphere, and by some wonderful trajection broke out again here. This was the expedient they found out to make their opinions consistent one with another; but this is a method to me altogether unconceivable; and, for my part, I do not love to be led out of my depth, leaning only upon Antiquity. How there could be any such communication, either above ground, or under ground, betwixt the two Hemispheres, does not appear, and therefore we must still suppose the Torrid Zone to have been the Barrier betwixt them, which nothing could pass either way.

We have now examin’d and determin’d the state of the Air, and of the Waters in the Primitive Earth, by the light and consequences of reason; and we must not wonder to find them different from the present order of Nature; what things are said of them, or relating to them in holy Writ, do testifie or imply as much; and it will be worth our time to make some reflection upon those passages for our further confirmation. Moses tells us, that the Rainbow was set in the Clouds after the Deluge; those Heavens then that never had a Rainbow before, were certainly of a constitution very different from ours. 2 Epist. Chap. 3. 5.And St. Peter doth formally and expresly tell us, that the Old Heavens, or the Ante-diluvian Heavens had a different constitution from ours, and particularly, that they were compos’d or constituted of Water; which Philosophy of the Apostle's may be easily understood,

if we attend to two things, first, that the Heavens he speaks of, were not the Starry Heavens, but the Aerial Heavens, or the Regions of our Air, where the Meteors are; Secondly, that there were no Meteors in those Regions, or in those Heavens, till the Deluge, but watery Meteors, and therefore, he says, they consisted of Water. And this shows the foundation upon which that description is made, how coherently the Apostle argues, and how justly he distinguisheth the first Heavens from the present Heavens, or rather opposeth them one to another; because as those were constituted of Water and watery Meteors only, so the present Heavens, he saith, have treasures of Fire, fiery Exhalations and Meteors, and a disposition to become the Executioners of the Divine wrath and decrees in the final Conflagration of the Earth.

This minds me also of the Celestial Waters, or the Waters above the Firmaments, which Scripture sometimes mentions, and which, methinks, cannot be explain’d so fitly and emphatically upon any supposition as this of ours. Those who place them above the Starry Heavens, seem neither to understand Astronomy nor Philosophy; and, on the other hand, if nothing be understood by them, but the Clouds and the middle Region of the Air, as it is at present, methinks that was no such eminent and remarkable thing, as to deserve a particular commemoration by Moses in his six days work; but if we understand them, not as they are now, but as they were then, the only Source of Waters, or the only Source of Waters upon that Earth, (for they had not one drop of Water but what was Celestial,) this gives it a new force and Emphasis: Besides, the whole middle Region having no other sort of Meteors but them, that made it still the greater singularity, and more worthy commemoration. As for the Rivers of Paradise, there is nothing said concerning their Source, or their issue, that is either contrary to this, or that is not agreeable to the general account we have given of the Waters and Rivers of the first Earth. They are not said to rise from any Mountain, but from a great River, or a kind of Lake in Eden, according to the custom of the Rivers of that Earth: And as for their end and issue, Moses doth not say, that they disburthen’d themselves into this or that Sea, as they usually do in the description of great Rivers, but rather implies, that they spent themselves in compassing and watering certain Countries, which falls in again very easily with our Hypothesis.

But to return to the Rainbow, which we mention’d before, and is not to be past over so slightly. This we say, is a Creature of the modern World, and was not seen nor known before the Flood. Moses (Gen. 9. 12, 13) plainly intimates as much, or rather directly affirms it; for he says, The Bow was set in the Clouds after the Deluge, as a confirmation of the promise or Covenant which God made with Noah, that he would drown the World no more with Water. And how could it be a sign of this, or given as a pledge and confirmation of such a promise, if it was in the Clouds before, and with no regard to this promise? and stood there, it may be, when the World was going to be drown’d. This would have been but cold comfort to Noah, to have had such a pledge of the Divine veracity. You'll say, it may be, that it was not a sign or pledge that signified naturally, but voluntarily only, and by Divine institution; I am of opinion, I confess, that it

signifi’d naturally, and by connexion with the effect, importing thus much, that the state of Nature was chang’d from what it was before, and so chang’d, that the Earth was no more in a condition to perish by Water. But however, let us grant that it signified only by institution; to make it significant in this sence, it must be something new, otherwise it could not signifie any new thing, or be the confirmation of a new promise. If God Almighty had said to Noah, I make a promise to you, and to all living Creatures, that the World shall never be destroy’d by Water again, and for confirmation of this, Behold, I set the Sun in the firmament: Would this have been any strengthning of Noah's faith, or any satisfaction to his mind? Why, says Noah, the Sun was in the Firmament when the Deluge came, and was a spectator of that sad Tragedy; why may it not be so again? what sign or assurance is this against a second Deluge? When God gives a sign in the Heavens, or on the Earth, of any Prophecy or Promise to be fulfill’d, it must be by something new, or by some change wrought in Nature; whereby God doth testifie to us, that he is able and willing to stand to his promise. God says to Ahaz, Isa. 7. Ask a sign of the Lord; Ask it either in the depth, or in the height above: And when Ahaz would ask no sign, God gives one unaskt, Behold, a Virgin shall conceive and bear a Son. So when Zachary was promis’d a SonLuke 1., he asketh for a sign, Whereby shall I know this? for I am old, and my Wife well stricken in years; and the sign given him was, that he became dumb, and continued so till the promise was fulfill’d. Isa. 38.

Judg. 7.So in other instances of signs given in external Nature, as the sign given to King Hezekiah for his recovery, and to Gideon for his victory; to confirm the promise made to Hezekiah, the shadow went back ten degrees in Ahaz Dial: And for Gideon, his Fleece was wet, and all the ground about it dry; and then to change the trial, it was dry, and all the ground about it wet. These were all signs very proper, significant, and satisfactory, having something surprising and extraordinary, yet these were signs by institution only; and to be such they must have something new and strange, as a mark of the hand of God, otherwise they can have no force or significancy. If every thing be as it was before, and the face of Nature, in all its parts, the very same, it cannot signifie any thing new, nor any new intention in the Author of Nature; and consequently, cannot be a sign or pledge, a token or assurance of the accomplishment of any new Covenant or promise made by him.

This, methinks, is plain to common Sense, and to every mans Reason; but because it is a thing of importance, to prove that there was no Rainbow before the Flood, and will confirm a considerable part of this Theory, by discovering what the state of the Air was in the Old World, give me leave to argue it a little further, and to remove some prejudices that may keep others from assenting to clear Reason. I know ’tis usually said, that signs, like words, signifie any thing by institution, or may be appli’d to any thing by the will of the Imposer; as hanging out a white Flag is calling for mercy, a Bush at the door, a sign of Wine to be sold, and such like. But these are instances nothing to our purpose, these are signs of something present, and that signifie only by use and repeated experience; we are speaking of signs of another nature, given in confirmation of a promise, or threatning, or prophecy, and given with design to cure our unbelief,

or to excite and beget in us Faith in God, in the Prophet, or in the Promiser; such signs, I say, when they are wrought in external Nature, must be some new Appearance, and must thereby induce us to believe the effect, or more to believe it, than if there had been no sign, but only the affirmation of the Promiser; for otherwise the pretended sign is a meer Cypher and superfluity. But a thing that obtain’d before, and in the same manner (even when that came to pass, which we are now promis’d shall not come to pass again) signifies no more, than if there had been no sign at all: it can neither signifie another course in Nature, nor another purpose in God; and therefore is perfectly insignificant. Some instance in the Sacraments, Jewish or Christian, and make them signs in such a sence as the Rainbow is: But those are rather Symbolical representations or commemorations; and some of them, marks of distinction and consecration of our selves to God in such a Religion; They were also new, and very particular when first instituted; but all such instances fall short and do not reach the case before us; we are speaking of signs confirmatory of a promise, when there is something affirm’d de futuro, and to give us a further argument of the certainty of it, and of the power and veracity of the Promiser, a sign is given: This we say, must indispensably be something new, otherwise it cannot have the nature, vertue, and influence of a sign.

We have seen how incongruous it would be to admit that the Rainbow appear’d before the Deluge, and how dead a sign that would make it, how forc’d, fruitless and ineffectual, as to the promise it was to confirm; Let us now on the other hand suppose, that it first appear’d to the Inhabitants of the Earth after the Deluge, How proper, and how apposite a sign would this be for Providence to pitch upon, to confirm the Promise made to Noah and his posterity, That the World should be no more destroy’d by Water? It had a secret connexion with the effect it self, and was so far a natural sign; but however appearing first after the Deluge, and in a watery Cloud, there was, methinks, a great easiness, and propriety of application for such a purpose. And if we suppose, that while God Almighty was declaring his promise to Noah, and the sign of it, there appear’d at the same time in the Clouds a fair Rainbow, that marvellous and beautiful Meteor, which Noah had never seen before; it could not but make a most lively impression upon him, quickning his Faith, and giving him comfort and assurance, that God would be stedfast to his promise.

Nor ought we to wonder, that Interpreters have commonly gone the other way, and suppos’d that the Rainbow was before the Flood; This, I say, was no wonder in them, for they had no Hypothesis that could answer to any other interpretation: And in the interpretation of the Texts of Scripture that concern natural things, they commonly bring them down to their own Philosophy and Notions: As we have a great instance in that discourse of St. Peter's, 2 Epist. c. 3. 5. concerning the Deluge, and the Ante-diluvian Heavens, and Earth, which, for want of a Theory, they have been scarce able to make sence of; for they have forc’dly appli’d to the present Earth, or the present form of the Earth, what plainly respected another. A like instance we have in the Mosaical Abysse, or Tehom-Rabba, by whose disruption the Deluge was made; this they knew not well what

to make of, and so have generally interpreted it of the Sea, or of our subterraneous Waters; without any propriety, either as to the word, or as to the sence. A third instance is this of the Rainbow, where their Philosophy hath misguided them again; for to give them their due, they do not alledge, nor pretend to alledge, any thing from the Text, that should make them interpret thus, or think the Rainbow was before the Flood; but they pretend to go by certain reasons, as that the Clouds were before the Flood, therefore the Rainbow; and if the Rainbow was not before the Flood, then all things were not made within the six days Creation: To whom these reasons are convictive, they must be led into the same belief with them, but not by any thing in the Text, nor in the true Theory, at least if Ours be so; for by that you see that the Vapours were never condens’d into drops, nor into Rain in the temperate and inhabited Climates of that Earth, and consequently there could never be the production or appearance of this Bow in the Clouds. Thus much concerning the Rainbow.

To recollect our selves, and conclude this Chapter, and the whole disquisition concerning the Waters of the Primitive Earth; we seem to have so well satisfied the difficulties propos’d in the beginning of the Chapter, that they have rather given us an advantage; a better discovery, and such a new prospect of that Earth, as makes it not only habitable, but more fit to be Paradisiacal. The pleasantness of the site of Paradise is made to consist chiefly in two things, its Waters, and its Trees, (Gen. 2 and Chap. 13. 10. Ezek. 31. 8) and considering the richness of that first soil in the Primitive Earth, it could not but abound in Trees, as it did in Rivers and Rivulets; and be wooded like a Grove, as it was water’d like a Garden, in the temperate Climates of it; so as it would not be, methinks, so difficult, to find one Paradise there, as not to find more than one.