WHEN we suspended the plumbline at the first adjustment of the Geodetic Apparatus, we established beyond all doubt the direction of the earth's radius, or the perpendicular at the initial station.

Poised upon the pivot of adjustment, the bubble in the graduated vial of the spirit level measured equal distances from the central division of the scale. The mercury in the 12-foot mercurial geodetic level stood

at equal altitudes in the perpendicular tubes, in demonstration of the fact that the level is at right angles with the perpendicular radius of the earth.

The plumb and level invariably tell the truth; they are silent witnesses testifying from the standpoint of unseen "energies," which man cannot bribe nor change to suit a theory. The bubble-shifts at the various stations throughout the line of survey, whether corroborating or denying preconceived opinions, must be accepted as conclusive.

With perpendicular and horizontal definitely fixed at the starting point in our survey and in our argument concerning the evidences afforded in the line projected, we have factors which constitute an indisputable basis of reference. Once leveled, the direction of our line was fixed, from which it was not possible to depart; the bolts which held together the brass facings on the adjusted right-angled cross-arms would admit of no change.

The very principles of construction of the apparatus compelled the maintenance of the rectiline from the beginning to the end. The line projected must terminate somewhere, either in space or in the water, according as the earth would be found to be convex or concave.

If the earth were convex, the line would extend into space, as before explained; as the line would proceed, the bubble in the spirit level would shift at each successive application, more and more toward the south from the central division of the scale, while the plumbline hanging in the direction of the perpendicular, or the earth's radii at the various stations, would hang toward the initial station. If concave, the

conditions and positions of the levels and plumb would be the reverse of those on a convex surface; if flat, they would be the same continually, as at the beginning of the line.

By reference to Cut 4, Plate 1, the relations of the plumb to an extension of the horizontal at the initial station may be clearly seen, as regards the convex, the flat, and the concave theories. In conjunction with the tests of levels and plumb, the observations of the Gulf horizon were made, as before explained.

At the beginning of the line, the straight-edges of the apparatus when in adjustment were parallel with the horizon. On a convex arc, the straight-edges and the horizon line would appear to converge toward the north with increasing angle, as the line proceeded; if flat, their original parallel relations would be apparent throughout the line; and if concave, the apparent convergence would be toward the south, or in the direction of the movement of the apparatus.

We present the evidences of the readings of the levels, plumb, and horizon, because the evidences afforded by these means are independent of any measurements of altitude of the line surveyed above the mean tide level; we offer them as corroborative of the measurements obtained.

It will be found upon comparison with the table of measurements in this chapter, that these evidences are in harmony with the measurements and facts which constitute the factors of our direct demonstration.

The spirit level was applied in test of position of sections at every twelfth adjustment throughout the

line. For the first several tests, the divergence of the water line and the air line was too slight to be detected by means of the level; and it was not until near the end of the first eighth-of-mile division of the line that any difference was thus manifest. The bubble had shifted a little--toward the north, or rear section of the apparatus. From the first point of the manifest deviation until the end of the line, the angle increased proportionately to the distance traversed.

This was corroborated also by the position of the plumbline, and the observed increase of angle between the straight-edges and horizon, always converging toward the south.

We have thus far referred to these angles in general terms; the question would arise, What were the actual angle measurements as ascertained by the levels, plumb, and horizon, at points where all these tests were applied? If there were variations, how great or small were the variations?

The divisions on the graduated scale of the spirit level were .075 of an inch apart; the plumb was suspended from top of the 4-foot right-angled cross-arms, and the angle read on plate at the bottom of the cross-arms; the 12-foot mercurial level determined the angle for 12 feet, while the observed horizon was related to straight-edges 36 feet in length, and therefore determined the angle for 36 feet.

We give below the results observed at the end of the first mile, the second mile, and at end of 2⅜ miles, at last adjustment of the apparatus in the southerly direction.

Spirit Level, shift of bubble toward north end of the vial, as measured on the graduated scale:

Plumbline, measurement on arc of 4 feet radius, as related to right-angled cross-arms: .

Mercurial geodetic level, indicating angle of divergence of air line and horizontal at points of test, for the space of 12 feet:

The Horizon, indicating angle for space of 36 feet, as accurately as could be measured with the eye at a distance of 15 feet from the apparatus:

These readings, taken as a basis of mathematical calculations, will be found to very nearly conform to the relations of chord and radii, over an arc of 25,000 miles circumference, and are evidences of the angles increased in about the proper ratio, as the surveyed line progressed from the beginning to the end. The chord, tangibly constructed, was constantly converging with the arc, as we have shown by the four independent sources of evidence; and we now purpose presenting such a network of facts of absolute and direct demonstration as to render our position invulnerable, and our premise impregnable.

From the Naples dock looking south, a white line in the Florida sand marks the line of excavations for emplacement of the standards of the Rectilineator, extending to Gordon's Pass, in the southern horizon. This white line is the actual mark we have made in the world,--our path to success, the route of demonstration. Carefully and patiently for eight weeks we followed this course, making precise adjustments,--

painstaking, careful, tedious, and trying work, by which the facts we are publishing were obtained.

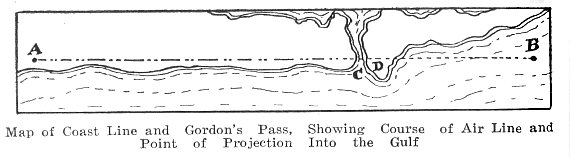

We diagram the Air Line, the coast line, and the water's surface to the extremity of the line, covering the space of 4⅛ miles. A is the point of beginning of the line at altitude of 128 inches; B is the point where the rectiline extended into the waters of the Gulf of Mexico. The coast line can be easily traced without lettering; C is Gordon's Pass; D, the long sand-bar extending into the Gulf, through an excavation in which the Air Line was projected; the excavation admitted of vision of the water horizon from the 2⅜ mile station, where the final adjustments of the apparatus were made.

All of the definite measurements of altitude of the line and of the minute angles of divergence were made with reference to the position of the apparatus from the beginning of the line to the end of the adjustments, covering a distance of 2⅜ miles; the line was tangibly built for this distance. The cross-arms extended 2 feet below the horizontal axis or middle line of the sections, and at the end of 2⅜ miles were within 7 inches of the ground; the axis of the apparatus was rapidly converging with the water level.

We had manipulated the apparatus as far as practicable and possible, within the limits of our conveniences

for operation from the starting point of 128-inch altitude. The Air Line at this point was 54 inches nearer the water's surface than at the beginning; whereas, if the earth were convex, the line would have been 54 inches above the vertical point of the original 128 inches, making a difference of 108 inches, or 9 feet, in the position of the apparatus from that really obtained.

For the reasons given above, the extension of the Air Line into the water, or a continuance of the line in any direction, we had to employ another method of survey. As the line would extend across the Pass and over the sand-bar, through the excavation, and into the Gulf south of the Pass, it was necessary to finish the line by a visual process.

In order that this might be done as accurately as possible, obviating any errors that might arise from the adjustment of such an apparatus as the engineer's level, parallel with the horizontal axis of the apparatus, two points on the Air Line surveyed by the apparatus, one-eighth of a mile apart, were taken as tile sighting stations; these points were tide staffs Nos. 19 and 20.

On these staffs we had left the record of the altitude of the Air Line. The large telescope provided with horizontal cross-hair, was adjusted at staff No. 19, so that its line of collimation was at the same altitude as the surveyed line at that point. On staff No. 20, one-eighth of a mile distant, a steel strip was fixed horizontally at altitude of Air Line at that point, upon which to train the telescope. When the telescope was adjusted so that the cross-hair was in line with the steel

strip, the simple matter of projecting the remainder of the line visually is easily comprehended.

At these distances from the beginning of the line, with the tending divergence toward the water, refraction and visual curvilineation would involve so small a factor of departure from the rectiline for the remaining distance as to give an approximately correct reading on the staffs to the end. Through the telescope, the steel strip and the cross-hair were observed to a point below the Gulf horizon--the visual line extending into the water south of the Pass.

The following diagram gives a perpendicular view of the line, showing the land elevation. XY represents

the arc of curvature; A, the beginning of the survey; B, the point of projection into the water; C, the Pass, and D, the sand-bar through which excavation was made; E, tide staff No. 19, with telescope; F, tide staff No. 20. The continuous line is the line surveyed by section adjustments; the dotted line is the portion of the Air Line projected visually.

For the purposes of measurement and calculation of ratio of curvature, it was necessary to locate the point on the Gulf where the line extended into the water. This was done by directing our sail-boat beyond the Pass, in line with the telescope axis. When the lower part of the hull appeared just above the cross-hair, it was obvious that the point was marked.

By means of our signal code, the observer at the telescope transmitted the information that the point was reached by the sailors in the boat, and the occupants on getting signal, went directly ashore, and consulting stakes, gave the distance as approximately 4⅓ miles from beginning of survey.

These observations were participated in by the visiting and investigating committee, as well as the Operating Staff, who conducted a repetition of the observations three days later.

At the time of the observations, sketches of the telescopic view were made, showing the boat on the Gulf where the Air Line was projected into the water, as the converging chord of arc; and for the benefit of the reader we herewith produce sketch, showing the cross-hair in telescope at tide staff No. 19, the picture of tide staff No. 20, with steel strip attached in line with the cross-hair.

The visual line connecting the same, extending beyond and projecting into the water, completed the experiment, the results having been proclaimed by the Founder of the Koreshan Cosmogony twenty-seven years previous to the demonstration on the Florida west coast.

For the purpose of further testing the apparatus, we retraced the surveyed line by means of the apparatus for the distance of ⅜ mile, taking the last forward adjustment as the first adjustment on the return survey. If the hair-line of the apparatus returned to the same point on the tide staffs, it would be a further demonstration of the accuracy of our work. An error of deviation from the rectiline would be applied on the return, and would consequently be

made manifest by having fixed points as bases of reference, such as were recorded upon the tide staffs on the forward survey.

Click to enlarge

Sketch of the Telescopic View

Showing Extension of the Air Line Into the Gulf Through Excavation South of Gordon's Pass; also Relation of Cross-hair and Steel Strip to Horizon and Boat in the Distance

Upon return to the staffs the hair-line of the apparatus fell upon nearly the same points, as per the figures in the table of measurements under the following subhead, demonstrating the remarkable accuracy and efficiency of the apparatus employed to make the

Click to enlarge

TABLE SHOWING ALTITUDE OF AIR LINE ABOVE DATUM LINE AT EVERY STATION OF SURVEY, WITH THE MEASURES COMPARED WITH THE CALCULATED CURVATURE SKETCH OF THE TELESCOPIC VIEW

first direct test of the earth's surface in the history of the world.

As the Rectilineator was moved forward, section by section, in the direction of the tide staffs, the relation of the hair-line of the sections to the 128-inch altitude, or secondary datum line, was easily obtained by measurement. At no place throughout the line of survey did the sections rise above the original 128-inch altitude.

At the end of the first 660 feet, where the calculated ratio would indicate .125 of an inch curvation, the hair-line of the apparatus fell .15 of an inch below the 128-inch altitude, being a difference of only .025 of an inch. This is in easy contrast with the conditions that would result if the earth curved downward instead of upward. If it were convex, the hair-line of the sections would have fallen about .125 of an inch above the 128-inch altitude. The tide staffs marked brilliant points of interest throughout the survey; for each measurement was a demonstration not only of the fact that the earth curved toward its chord, but also the ratio of its concavity.

For easy reference and definite record, we have condensed all of the facts of measurements of the Koreshan Geodetic Survey into the preceding table of distances and altitudes, by means of which the results of our work may be easily compared with the calculated ratio, and how nearly, at each tide staff, the hair-line of the apparatus came to indicating the ratio which we have since calculated, and here present for comparison and study.

It will be noticed that the difference between the measured and. the calculated ratios increases toward the end of the survey; the apparent rapid approach of the line to the water's surface after 2¼ miles had been surveyed is due, not to actual approach to the mean water level of even curvature, nor to inaccurate work or measurements of the tide levels, but to the crowding of the waters around the mouth of the Pass, creating a slight irregularity in the water level in that vicinity.

It will also be noticed that the line projected into ( the water at the distance of approximately 4¼ miles instead of 4 miles, which is due to refraction and incurvation of the visual lines from the 2⅜ miles station to the water's surface beyond the Pass.

It may be asked, What would be the facts of measurement if such survey as ours were made upon a convex surface? We append table of comparative results for reference, study, or test by calculation. Having two parallel arcs; the mean tide level, and the secondary datum line, connected by staffs of 128 inches altitude as fixed bases of reference, it may be seen that on a convex earth, instead of the air line falling below the vertical point of every staff, it would rise above, and increase in excess of altitude above the original 128 inches as to the square of the distance.

For instance; at the end of the first mile, instead of the surveyed line falling 8.02 inches below the secondary datum line, it would rise about as far above, making a difference of about 16 inches in the altitude of the line on the concave, and the line on the convex

earth; while at the end of 4⅛ miles, instead of the line extending into the water, the line would be projected

Click to enlarge

TABLE CONTRASTING AIR LINE AS SURVEYED, WITH CALCULATED RESULTS UPON CONVEX SURFACE

out into space, 136.125 inches above the original 128 inches, making a difference between the two theories of 264.125 inches, or about 22 feet, in 4⅛ miles.

If the reader will study the construction of the Rectilineator and the methods used in operating same, it will be clearly understood that we did not make an error of 22 feet in running 4⅛ miles.

In presenting the foregoing line of experiments, both optical and mechanical, we are giving to the world the benefit of much painstaking effort in deter-mining facts as to the real contour of the surface of the earth upon which we live.

In conducting the different lines of investigation presented, we have tried to be honest with ourselves and those who investigate our work as detailed. The conclusions reached are irrefutable. The character, honesty of purpose, and ability of those who conducted these experiments we willingly leave to the decision of the reader.