Click to enlarge

Architecture, Mysticism and Myth, by W.R. Lethaby, [1892], at sacred-texts.com

|

'And after skewed hym the nyne spheris |

THE number seven is written on the sky. What time the seven planets were counted and individualised is beyond all history; probably not two in a hundred even now guess at any other planet than Venus; probably not two in a thousand have ever seen Mercury, certainly not without a telescope; yet all of them we find distinguished by names and grouped together as errant bodies among the fixed stars in the earliest traditions:—(1) The Sun, (2) the Moon, (3) Mars, (4) Mercury, (5) Jupiter, (6) Venus, (7) Saturn.

The first known and named probably of all constellations, the Great Bear, always visible above the horizon, 'never bathing in ocean,' as Homer has it, is a group of seven. The lesser Bear has the same form, which is repeated a third time by the great square of Pegasus, and the three bright stars in Andromeda and Perseus. Seven also are the symmetrical and splendid stars of Orion. In France, the Pleiades are still called the 'seven stars,' and the

north is named the Septentrion, from the stars of the Great Bear.

The planets gave their names to the days of the week, and still distinguish them all over the world from France to China, and they are but slightly obscured for us by their northern names.

The seven days of the week are the nearest whole number to one-fourth of a month, a moon's quarter. The two days completing the month of thirty days were in Assyria intercalary.

Immense has been the influence of this magic number in philosophy, material and metaphysical. The life of man has been divided into seven ages. The first seven are the years of infancy. At three times seven—twenty-one—we become 'of age.' Three times twenty-one is the 'grand climacteric;' and seventy years is put as the time to die.

So the life of the world was in Middle Age histories divided into seven eras, of which we are in the last. There were seven material heavens; this middle world was divided into a like number of zones or 'climates,' and the under world into as many depths. In the philosophy of the schools every factor of the universe had a sevenfold division.

In the Cursor Mundi it is remarked that there are seven holes in the head, 'for maister sterres are there seven.'

So absorbing has been the nature of this number, that where groups occur, of anything from four to a dozen, let us say, they are almost sure to be 'seven sisters,' or 'seven brethren.' Sevenoaks, the seven hills of Rome, or of Constantinople, the seven holy cities of India, the seven architectural wonders of the world. Mr. Ruskin tells us he found great difficulty in limiting his 'seven lamps' so that they should not become eight or nine.

The seven planets have had a potent influence over architecture and the arts.

The sun, the moon, and the five other planets were not only observed to move independently of the 'sphere' of the fixed stars, but independently of each other, in varying periods. As the whole moving heaven of the 'fixed stars' was a solid 'firmament' studded with stars revolving around a pivot, the earth mountain; so, as the system was perfected, other transparent spheres had to be imagined, one for each planet, carrying it around in its due time. The heavenly mountain of the gods is thus either entirely celestial, the exterior of our firmament, and the whole seven successive domed heavens; or it is the central mountain of this lower world. the prop and pole of the heavens, divided into seven stages, one to each planetary sphere. Practically it is impossible to keep these two notions separate, and to say which is the Olympus—the stepped mountain supporting the heavens, or the seven-fold heavens itself. Dr. Rink, speaking of the Esquimaux, says: 'The upper world, it would seem, may be considered identical with the mountain, round the top of which the vaulted sky is for ever circling.' Olympus, to the Greeks, was many peaked, or of many layers, like the stratum without stratum of the Iranian mountain of the stars. By the addition of a sphere for the fixed stars, and an outer and immovable envelope, the seven became nine heavens.

In the Vedas there are seven heavens. 'In the Hindu cosmogony,' writes Sir G. Birdwood, 'the world is likened to a lotus flower floating in the centre of a shallow circular vessel, which has for its stalk an elephant, and for its pedestal a tortoise. The seven petals of the lotus flower represent the seven divisions of the world, as known to the ancient

[paragraph continues] Hindus, and the tabular torus, which rises from their centre, represents Mount Meru, the ideal Himalayas (Himmel), the Hindu Olympus. It ascends by seven spurs, on which the seven separate cities and palaces of the gods are built, amid green woods and murmuring streams, in seven circles placed one above another.' Here is a tree which perfumes the whole world with its blossoms, a car of lapis lazuli, a throne of fervent gold; 'and over all, on the summit of Meru, is Brahmapura, the entranced city of Brahma, encompassed by the sources of the sacred Ganges, and the orbits in which for ever shine the sun and silver moon and seven planetary spheres.' The old Japanese poems translated by Mr Chamberlain speak of a mountain at the 'earth's acme or omphalos, which extended even to the skies; on its summit was a beautiful house.'

The modern view in Siam is similar. Mr. Carl Bock writes: 'According to Laosian idea, the centre of the world is Mount Zinnalo, which is half under water and half above. The sub-aqueous part of the mount is a solid rock, which has three root-like rocks protruding from the water into the air below. Round this mountain is coiled a large fish of such leviathan proportions that it can embrace and move the mountain; when it sleeps the earth is quiet, but when it moves it produces earthquakes.' 'Above the earth and around this great mountain is the firmament, with the sun, the moon, and the stars. These are looked upon as the ornaments of the heavenly temples. Above the water is the inhabited earth, and on each of the four sides of Mount Zinnalo are seven hills, rising in equal gradations one above the other, which are the first ascents the departed has to make.'

The planets themselves, which were affixed to their several spheres, were apparently thought of as having the nature of self-lustrous metals or gems, as they

were perceived to be diversified in colour—the golden sun, the silver moon, the red Mars of war. Thus the names of the several precious stones were given to the spheres.

In the Mohammedan scheme, as we have seen, the seven spheres have these distinctive colours. The first is described as formed of emerald; the second, of white silver; the third, of large white pearls; the fourth, of ruby; the fifth, of red gold; the sixth, of yellow jacinth; and the seventh, of shining light.’

Such being the conception of a holy mountain whose top reached to heaven; we need not wonder, we may expect to find many local identifications of it in the inaccessible snow-capped mountains of Pamir or the Himalayas; in Ararat, Parnassus, and the Thessalian Olympus. Inferior sites would also be artificially improved, thus Lenormant, in his article on Ararat and Eden (Contemp. Rev., Sept. 1881), thinks it clearly proved that Solomon and Hezekiah had this idea in the distribution of the waters which flowed from under the Temple in four streams, one of which was named Gihon. He quotes Obry: 'The Buddhists of Ceylon have endeavoured to transform their central mountain, Peak of the Gods, into Meru, and to find four streams descending from its sides to correspond with the rivers of their paradise.' And Wilford, in vol. viii. of 'Asiatic Researches,' says the early kings of India were fond of raising mounds of earth called 'Peaks of Meru,' which they reverenced like the holy mount. One of these near Benares bore an inscription which makes this clear. A country was divided into seven, nine, or twelve nomes or provinces, and the people into as many castes or tribes.

The Chaldeans had early perfected this universe of seven spherical strata, and with them we have

stupendous architectural structures, known as Ziggurats, erected, 'as an imitation or artificial reproduction of the mythical mountain of the assembly of the stars' (Ararat and Eden).

'Now, the pyramidical temple is the tangible expression, the material and architectural manifestation, of the Chaldaio-Babylonian religion. Serving both as a sanctuary and as an observatory for the stars, it agreed admirably with the genius of the essentially siderial religion to which it was united by an indissoluble bond' ('Chaldean Magic').

These structures belong to a class not properly temples. They are rather Mounts of Paradise—terraced altars. 'God Thrones' might best explain their purpose. They represent the world from without as a seat rather than a shrine for the Deity. If the word temple is here used, it is only in deference to custom.

Herodotus describes the Ziggurat of Babylon thus: 'The sacred precinct of Jupiter Belus, a square enclosure two furlongs each way, with gates of solid brass, was also remaining in my time. In the middle of the precinct there was a tower of solid masonry, a furlong in length and breadth, upon which was raised a second tower, and on that a third, and so on up to eight. The ascent up to the top is on the outside by a path which winds round all the towers. When one is about halfway up, one finds a resting-place and seats, where persons are wont to sit sometime on their way to the summit. On the topmost tower there is a spacious temple.'

This great metropolitan 'God Throne,' Perrot gives as the type of the Chaldean temple; and from the mounds and the temples depicted on the slabs, he has, together with the architect M. Chipiez, made a series of restorations in the volumes on the Art of Babylon and Assyria. He says: 'In spite of the

words of Herodotus, M. Chipiez has only given his tower seven stages, because that number seems to have been sacred and traditional, and Herodotus may well have counted the plinth or the terminal chapel in the eight mentioned in his description.'

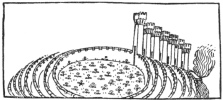

Mr George Smith, indeed, deciphered a tablet which actually gave the dimensions of this Ziggurat for all the seven stages. The bottom stage was 300 feet square and 110 feet high; the second, 260 feet sloping upwards, and 60 feet high; the third, 200 feet, and 20 feet high; fourth, fifth, and sixth, 170, 140, 110 feet respectively, each 20 feet high. And the top stage, the seventh (evidently the sanctuary, from its change of form), was oblong, So by 70 feet, and 50 feet high; the whole height being thus 300 feet, exactly the same as the base. These dimensions are set out in the drawing that forms the frontispiece, which is believed to be the first published drawing founded on these measurements; that of Perrot and Chipiez being entirely conjectural. However doubtful the translation into English measure may be, the form and proportion remain, and the result is a majestic and mysterious suggestion of volume and stability.

Herodotus also gives an account of the city and palace of Ecbatana of the Medes: 'This fortification is so contrived that each circle was raised above the other by the height of the battlements only. The situation of the ground, rising by an easy ascent, was very favourable to the design. But that which was particularly attended to is that, there being seven circles altogether, the king's palace and the treasury are situated within the innermost of them. The largest of these walls is about equal in circumference to the city of Athens. The battlements of the first circle are white; of the second, black; of the third,

purple; of the fourth, blue; of the fifth, bright red. Thus the battlements of all the circles are painted with different colours; but the two last have their battlements plated, the one with silver, the other with gold.'

Erech, the old sacred city of the Chaldeans, is called on a tablet 'The City of the Seven Zones or Stones' (Sayce).

At Borsippa, close to Babylon, there was a very ancient terraced temple or Ziggurat; it was restored by Nebuchadnezzar, and an inscription of his is preserved, which says: 'I have repaired and perfected the marvel of Borsippa, the temple of the seven spheres of the world. I have erected it in bricks which I have covered with copper. I have covered with zones, alternately of marble and other precious stones, the sanctuary of God.' Rawlinson writes: 'The ornamentation of the edifice was chiefly by means of colour. The seven stages represented the seven spheres, in which moved, according to ancient Chaldean astronomy, the seven planets. To each planet fancy, partly grounding itself upon fact, had from of old assigned a peculiar tint or hue. The sun was golden; the moon, silver; the distant Saturn, almost beyond the region of light, was black; Jupiter was orange (the foundation for this colour, as for that of Mars and Venus, was probably the actual hue of the planet); the fiery Mars was red; Venus was a pale Naples yellow; Mercury, a deep blue. The seven stages of the tower-like walls of Ecbatana gave a visible embodiment to these fancies. The basement stage, assigned to Saturn, was blackened by means of a coating of bitumen spread over the face of the masonry; the second stage, assigned to Jupiter, obtained the appropriate orange colour by means of a facing of burned bricks of that hue; the third stage,

that of Mars, was made blood-red by the use of half-burned bricks formed of a red clay; the fourth stage, assigned to the Sun, appears to have been actually covered with thin plates of gold; the fifth, the stage of Venus, received a pale yellow tint from the employment of bricks of that colour; the sixth, the sphere of Mercury, was given an azure tint by vitrifaction, the whole stage having been subjected to an intense heat after it was erected, whereby the bricks composing it were converted into a mass of blue slag; the seventh stage, that of the Moon, was probably, like the fourth, coated with actual plates of metal. Thus the building rose up in stripes of varied colour, arranged almost as Nature's cunning arranges the hues of the rainbow—tones of red coming first, succeeded by a broad stripe of yellow, the yellow being followed by blue. Above this the glowing silvery summit melted into the bright sheen of the sky' (Ancient Monarchies).

The order in which the stages encircled one another spreading outwards to the base, represented in correct sequence the orbits of the planets, as was supposed, around the earth. The small orbit of the moon at the top; the sun taking the place of the earth, as it appears to journey through the twelve signs of the year; and Saturn last of all. Generally, however, as in the walls of Ecbatana, the sun and moon lead the planets in the order of the days of the week. The order in which the days of the week are named after the planets, Mr Proctor says, is obtained in the following manner. If all the hours throughout the week are dedicated to the planets in the sequence of their observed distances—Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, Sun, Venus, Mercury, Moon—then beginning with Saturday the planet which rules the first hour of the next day will be the Sun, and of the next the Moon, and so on

for all the days of the week. This explanation takes for granted that the days were divided into twenty-four parts before the seven days were named after the planets.

Another of these Ziggurats, an adjunct to Sargon's palace, was discovered by M. Place at Korsabad, and by him named the Observatory; this was 143 feet at the base, and is supposed to have been the same height. Three whole stages and part of a fourth, were still in existence. 'Coloured stucco, varying in hue from one stage to another, was still visible, and confirmed the statement of Herodotus as to the traditional sequence of the tints.' The stages of this building were each about 20 feet high. The first was white; the second, black; the third, red; the fourth, white; and fragments of other colours were found in the débris.

The plan of one of these temples, with the path making seven complete circuits before it reaches the centre and the top, is very much the same as the traditional form of the labyrinth of Crete, and intimately connected with it in origin; or rather, they are complementary ideas, the one representing the seven spheres of the overheavens, the other the seven circles of the under-world. But we will try to follow this clue of the labyrinth in the next chapter.

According to the poet Nonnos, Thebes was built by Cadmus circular in form; the main streets from the centre went north, south, east, and west, and every one of the seven gates was consecrated to a planet. It was thus quite a celestial city, and the seven gates retained their planetary designations in historical times.

In an article in the 'Journal of the Geographical Society' (vol. x.), Sir H. Rawlinson quotes, from an historian of Armenia of the fifth century of our era, a description of Atropatene, 'the second Ecbatana, or

the seven-walled city.' He adds: 'The story of the seven walls is one of Sabæan origin, and the seven colours are precisely those which are used by the Orientals to denote the seven great heavenly bodies or the seven climates in which they revolve. Thus Nizami describes a seven-bodied palace, built by Bahram Gur (the Sassanian monarch), nearly in the same terms as Herodotus. The palace dedicated to Saturn, he says, was black; that of Jupiter, orange, or, more strictly, of sandal wood colour; of Mars, scarlet; of the Sun, golden; and Venus, white; of Mercury, azure; and of the Moon, green—a hue which is applied by the Orientals to silver.' Sir H. Rawlinson doubts the actual existence of seven concentric walls at Ecbatana with their several metals and colours, but thinks it likely that the city was dedicated to the heavenly bodies. In another account of Persian monumental symbolism, we find the whole series, not as before the Sun and Moon alone, represented by metals—The seven planetary metals. Origen quotes Celsus as to the mysteries of Mithras—'For in the latter there is a representation of the two heavenly revolutions, of the movement, to wit, of the fixed stars, and of that which takes place among the planets, and of the passage of the soul through these. The representation is of the following nature. There is a ladder with lofty gates, and, on the top of it, an eighth gate. The first gate consists of lead, the second of tin, the third of copper, the fourth of iron, the fifth of a mixture of metals, the sixth of silver, and the seventh of gold. The first gate they assign to Saturn, indicating by the lead the slowness of this star; the second to Venus, comparing her to the splendour and softness of tin; the third to Jupiter, being firm and solid; the fourth to Mercury, for both mercury and iron are fit to endure all

things, and are money-making and laborious; the fifth to Mars, because, being composed of a mixture of metals, it is varied and unequal; the sixth, of silver, to the Moon; the seventh, of gold, to the Sun, imitating the colours of the two latter.'

The Buddhists held an exactly similar view as to the transmigration through several heavens before the heaven of heavens of Buddha was reached—the ascent, in other words, of the stages of the holy Mount Meru. We have shown before that the tope was the microcosm of the material sky as imagined by the Buddhists. These, too, would seem to have had their zones of planetary colours; for Fa-Hian, the Chinese pilgrim to the Buddhist shrines of India and Ceylon, at the end of the fourth century, describes nearly every tope he sees as 'covered with layers of all the precious substances,' 'the seven precious substances' (Legge). These precious substances are given by Mr Rhys Davids as gold, silver, lapis-lazuli, rock crystal, rubies, diamonds or emeralds, and agate. Major Cunningham gives a similar list, substituting amethyst for the diamond. In the tope at Sanchi, with the relics, he found seven beads of the 'precious things.' Indeed, we are told that after Buddha's enlightenment, a Raja built a hall for him of the seven precious substances, where he sat on a seven-gemmed throne.

Seven or nine-staged buildings were common all over India, Ceylon, Burmah, and Java, as Mr Fergusson's third volume sufficiently shows. All these, according to Col. Yule (Jour. R. Asiatic Soc. 1870), symbolised the mundane system. He quotes with approval from Koeppen: 'In Tibet, we are told every orthodoxly-constructed Buddhist temple either is, or contains, a symbolical representation of the divine regions of Meru, and the heaven of the gods, saints, and Buddhas rising above it.' He

then describes the 'Pagoda' at Mengoon, in Burmah, as being 'intended as a complete symbolical representation or model of Mount Meru,' as it rises in seven-terraced stages, surrounded by jagged parapets of 'mountainous outline,' which figure the several zones of the heavenly mount. The Pagoda of Rangoon stands on a terrace 900 by 700 feet, and 166 feet high; there are four flights of steps, the eastern being the most holy. On this terrace stands the central shrine, 1355 feet round, and 370 high; this was surmounted by tiers of 'Umbrellas,' to which were hung multitudes of gold and silver bells of fabulous worth, and the whole mass was gilt. 'The central edifice represents Mount Meru, and the circle of smaller buildings represents the mountains outside the world-girdling sea' 'The Burman,' Shway Yeo).

A remarkable temple at Jehol, in Mongolia, is described as 'a series of square buildings, each series higher than the other, till the last, which is eleven storeys high, and 200 feet at least square; the storeys are painted red, yellow, and green alternately . . . the tiles of the roof also are blue' (Williamson's Journeys). The Heavens are nine in the Edda: 'I mind me of nine homes of nine supports. The great mid-pillar in the earth below.' Also in the Kalevala. 'The nine starry vaults of ether.' In China, long before Buddhist influence, the same symbolism obtained. Professor Legge gives a prayer addressed to Shang Ti (Heaven), dwelling in the sovereign heavens, looking up to the lofty nine-storied azure vault.' The 'Altar to Heaven' in Pekin, where this worship was celebrated, was in existence twelve centuries before our era. It consists of a triple circular terrace 210 feet wide at the base, 150 in the middle, and 90 at the top. 'The platform is laid with marble

slabs, forming nine concentric circles; the inner circle consists of nine stones round the central stone, which is a perfect circle.' On this slab, 'flawless as a piece of the cerulean heavens,' the Emperor kneels. 'Round him on the pavement are the nine circles of as many heavens, consisting of nine stones, then eighteen, then twenty-seven, and so on in successive multiples of nine, till the square of nine, the favourite number of Chinese philosophy, is reached in the outermost circle of eighty-one stones. Four flights of steps of nine each lead down to the middle terrace, where are placed tablets to the spirits of the Sun, Moon, and Stars, and the Year God.'

The order followed in worship is that of court ceremonial. First come the nine orders of nobility, and then the nine ranks of officers—the distinctions being indicated by different coloured balls on their caps: the Emperor being at the vertex (Edkins in Williamson's Journeys). Not only have we here the temple of heaven, but the celestial hierarchy and ritual.

Mr Squier, an American archæologist, points out a similar meaning in the structures of Mexico. 'The Mexicans believed in nine heavens, their conception differing only in this respect from that of the Hindus. The first or superior heaven was called "The Residence of the Supreme God;" the second, or next inferior, the Azure Heaven; the next, or seventh, the Green Heaven,' etc. And quoting from Lord Kingsborough: 'The Mexicans believed in nine heavens, which they supposed were distinguished from each other by the planets which they contained, from the colour of which they received their several denominations' (a native drawing is given as illustration, showing the nine heavens as so many ceilings studded with stars). 'It is not an assumption supported only by analogy that the Mexican teocalli were symbolical structures.'

[paragraph continues] (He then cites Boturini's account of the reformer king of Tezcuco.) "This celebrated Emperor built a tower of nine stages, symbolising the nine heavens, and upon its summit erected a dark chapel, painted within of the fairest blue, with cornices of gold, dedicated to God the Creator, who has His seat above the heavens"’ (The Serpent Symbol in America). Prescott says the tower was 'nine stories high, to represent the nine heavens; a tenth was surmounted by a roof painted black, and profusely gilded with stars on the outside, and incrusted with metals and precious stones within. He dedicated this to the unknown God, the Cause of causes.' The finds at Warka, and some inscriptions, would go to show that the shrines in Chaldea surmounting the Ziggurat were also of the fairest blue, lapis-lazuli. Maspero and Perrot are disposed to accept the account of a Greek writer that the great Pyramid was decorated in zones of colour, with the apex gilt; and it would seem more than a coincidence that the earliest pyramids, attributed to the first four dynasties, should be in stages. That of Sakkarah still has six steps, decreasing from thirty-eight feet high at the bottom to twenty-nine feet for the top, in remarkable resemblance to the Ziggurat of Babel. And Mr Petrie has found that the pyramid of Medum was built in seven degrees before the outer and continuous casing was applied, 'producing a pyramid which served as a model to future sovereigns.'

In the outer circle of his underworld Dante sees the fields of peace of the great pagan dead. From his description and Botticelli's drawing, in the 1481 edition, with its seven circular walls, a high tower gateway in each, an Assyrian would know at once it was the city of the dead:—

According to Sir George Birdwood, the regents of the planets that govern the days of the week in India are distinguished by the following colours: (1) The regent of the Sun and the first day of the week, bright yellow; (2) of the Moon, white; (3) of Mars, red; (4) of Mercury, yellow; (5) of Jupiter, also yellow; (6) of Venus, white; (7) of Saturn, black.

In making thrones, the same author says, 'The colour of any stone used should be that of the planets presiding over the destiny of the person for whom the throne is made.' We have already seen Buddha's throne, made of all the seven planetary substances, and that the vast pyramid structures of Babylon were thrones for the god to which the coloured terraces formed so many steps.

The tradition of the throne on the seven heavenly steps lasts on into the Middle Ages. A thirteenth century MS. at Heidelberg, which figures the universe,

shows the Throne of the Majesty standing on seven decreasing circular steps forming to the earth the vaults of heaven. An inscription, 'seven steps in fashion of a hollow vault,' makes the meaning clear, and is especially valuable as giving us the scheme of Dante's Paradise, which has so puzzled the commentators. Dante, standing at the apex on the outer material heaven, looks up and sees over and around, another and another expanse. As he stands centrally

under them, the steps of the throne form an inverted amphitheatre, 'the white rose'—

[paragraph continues] The throne high over all becomes a type; and all thrones must have seven steps. Compare the description of Solomon's throne in the Book of Chronicles and Josephus: 'Moreover the king made a great

throne of ivory, and overlaid it with pure gold. And there were six steps to the throne, with a footstool of gold, which were fastened to the throne, and stays on each side of the sitting place, and two lions standing by the stays; and twelve lions stood there on the one side, and on the other side upon the six steps. There was not the like made in any kingdom' (2 Chron. ix. 17). Josephus varies slightly, but in both are the seven pairs of lions standing at seven degrees of height: “A throne of prodigious bigness, of ivory, and having six steps to it, on every one of which stood on each end of the steps two lions; two other lions standing above also; but at the sitting place of the throne hands came out to receive the king; and when he sat backward, he rested on half a bullock that looked towards his back; and all was fastened together with gold.’ In the Talmud are also the seven pairs of animals, but, to add some ingenuity, the animals and birds are such as prey on one another, 'symbolical of enemies dwelling together in peace.' 'And the wolf shall then dwell with the sheep.' Over the throne was hung a chandelier of gold, with seven branches, ornamented with roses, knops, bowls, and tongs; and on the seven branches were the seven names of the patriarchs engraven—Adam, Noah, Shem, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, and Job.

The Arab writers add to the wonders. Two lions were made for the throne by genii and set at the foot; two eagles were placed above it; and when the king mounted it, the lions stretched out their paws, and when he sat down the eagles shaded him with their wings. All this seems to have been achieved in the throne in the imperial palace at Constantinople—constructed in imitation of, and called Solomon's throne—where the beasts of gold rose to their feet and roared, and close by was the golden tree and singing birds.

[paragraph continues] But the steps should be adorned with the planetary colours, like the throne of Prester John, as vouched for by Sir John Maundeville. 'Of the steps approaching his throne where he sits at meat, one is of onyx, another of crystal, another green jasper, another amethyst, another sardonyx, another cornelian, and the seventh on which he sets his feet is of chrysolite. All these steps are bordered with fine gold, with other precious stones, set with great orient pearls. The sides of the seat of his throne are of emeralds and bordered full nobly with gold, and dubbed with other precious stones and great pearls. All the pillars in his chamber are of fine gold, with precious stones, and with many carbuncles, which give great light by night to all people. And although the carbuncle gives light enough, nevertheless at all times a vessel of crystal, full of balm, is burning to give good smell and odour to the emperor, and to expel all wicked airs and corruptions.'

In the 'Romance of Alexander' the throne of the conquered Darius has seven such steps. They were of amethyst, smaragdine, topaz, garnet, adamant, gold and earth. The first keeps one from drunkenness, the second protects the sight, the topaz reflects an inverted image, the garnet is the brightest, the adamant, which is the hardest, attracts ships, gold is the chief of metals, and the earth reminded the King that he too was but dust.

Fa-Hian, in India, in the fourth century, sees a relic of Buddha exposed on 'a pedestal of the seven precious substances, and covered with a bell of lapis lazuli both adorned with pearls.'

In Egypt the covering of the throne, and its footstool, figured the blue star set expanse of heaven. In Mexico also it was of azure. The King has everywhere been a god seated on the heavenly throne. There is still reason behind the most imaginative design.

The septfold planetary system holds in Heraldry. To quote from Baron Portal on the symbolism of colour:—'All coats of arms, says Anselm in the Palais de l’Honneur, are differenced by two metals, five colours, and two furs. The two metals are, or and argent; the five colours are azure, gules, sable, sinople (green), porpure; and the two furs ermine and vair. Aristotle in his time gave names to the metals and colours according to the seven planets. Or, was called the Sun; argent, the Moon; azure, Jupiter; gules, Mars; sable, Saturn; sinople, Venus; and porpure, Mercury, and each god was painted with his appropriate metal and colour.' In the Middle Ages, when the heavenly spheres had been increased to nine, with nine orders of spirits to govern them, the sevenfold arrangement of the metals and tinctures was increased to nine by two other tinctures—tenné (tawny), orange, and sanguiné, blood colour. The 'Boke of St. Albans,' compiled in the fifteenth century by Dame Juliana Berners, gives us the Mediæval lore as to heraldry and the ninefold colours:—

'The lawe of Armes the wiche was effigured and begunne before any lawe in the worlde, both the lawe of nature and before the commandementis of God.

'And this lawe of armys was grounded upon the IX dyveris orderys of angels in heven encrowned with IX dyveris precious stonys of colouris and of vertuys dyveris also of them are figured the IX colouris in armys.

'The first stone is calde Topazion, signyfiyng gold in arrays' (its virtue is truth), etc., etc.

The seven or nine perfect heraldic tinctures are thus the precious stones and metals of the seven planets or nine heavens. Well may Lydgate say of these stones ideally used in blazoning arms:—

[paragraph continues] In old-fashioned heraldry this tradition is preserved, and the tinctures called either by their ordinary heraldic names, by the names of gems, or of the planets, the first being used to blazon the coats of commoners, the gems for nobles, and the planets for sovereign princes.

|

Or |

Topaz |

Sol |

|

Argent |

Pearl |

Luna |

|

Sable |

Diamond |

Saturn |

|

Gules |

Ruby |

Mars |

|

Azure |

Sapphire |

Jupiter |

|

Vert |

Emerald |

Venus |

|

Porpure |

Amethyst |

Mercury |

[paragraph continues] The natural colours of the planets as they appear to the eye, or under a low power, are said to be

|

Saturn |

. . |

Deep bluish. |

|

Jupiter |

. . |

White. |

|

Venus |

. . |

Yellow. |

|

Mars |

. . |

Red. |

|

Mercury |

. . |

Pale blue. |

In comparing the lists, the Sun and Moon are the two metals, Mars is always red, Saturn always black, Venus is yellow or green, Mercury blue or purple, and Jupiter is the least certain. The heraldic correspondences given in the Palais de l’Honneur may perhaps be accepted as authoritative. The significance of colour is thus given by a modern magician (Eliphas Lévi): 'Those who love blue are idealists and dreamers; those who like red are materialistic and passionate; yellow, fantastic and capricious; green, mercantile and crafty; those who give their preference to black are ruled by Saturn.' This accords with the rule of the planets over the several temperaments, as we preserve it in ordinary speech—Jovial, Mercurial, and Saturnine or Melancholy.

We have seen above the association of the metals with the seven stars; their correspondence is sufficiently obvious, and they share in modern science the same signs, and in one case the same name. There is a great deal of astrology in the sciences yet.

[paragraph continues] Chaucer gives a list identical with this except that the quicksilver of Mercury is contracted to silver. Gower in the 'Confessio Amantis' gives similar correspondences, except that 'Jupiter the brass bestoweth.'

In the East the perfect metal was naturally an alloy of all these.

Once grasp the colours and qualities of the seven planets, and you possess the master key of Astrology. As these powers might be present in the twelve houses of the heavens devoted to Birth, Riches, Marriage, etc.; so would the fortune of the subject be influenced. Two Capitals of the Ducal Palace at Venice show us how they rule Man and the Sciences; one depicting the seven ages, the other the seven liberal arts.

|

The Moon |

governs |

Infancy. |

|

Mercury |

„ |

Boyhood. |

|

Venus |

„ |

Adolescence. |

|

Sun |

„ |

Young Manhood. |

|

Mars |

„ |

Manhood. |

|

Jupiter |

„ |

Age. |

|

Saturn |

„ |

Decrepitude. |

[paragraph continues] The seven arts were Grammar, Logic, Rhetoric, Arithmetic, Geometry, Music, and Astronomy.

The traditional association of colours and stones with the planets is barely yet extinct in the West,

where old brooches may be seen of six coloured stones, and lavas set round a seventh central one, all with carved heads of the planets, and at the centre the rayed head of Apollo. In the East it is well understood. The gorgeous gold treasure from Burmah in the Indian Museum which has the splendour that only half barbaric work ever attains to, the bloom of red gold, and the profuse setting of uncut stones mesmerising the imagination into exaltation, has on most of the pieces eight precious stones set round an enormous ruby as large as a nut. This symbolic group is called Nauratan (nine gems). Throughout India 'they are the only stones esteemed precious.'

To come back again to the Chaldean world mountain, home of the gods, birthplace of the nations, and, like Meru, a mountain of precious stones. In the tablets it is called Nizar, and its summit by a name familiar to us as that of its architectural representation—Ziggurat. Madame Ragazoin puts this symbolic purpose clearly before us. 'So vivid was the conception in the popular mind, and so great the reverence entertained for it, that it was attempted to reproduce the type of the holy mountain in the palaces of their kings and the temples of their gods.'

'As the gods dwelt on the summit of the Mountain of the World, so their shrines should occupy a position as much like their residence as the feeble means of man would permit. That this is no idle fancy is proved by the very name of "Ziggurat," which means "mountain peak," and also by the names of some of these temples; one of the oldest, and most famous, indeed, in the City of Assur was named "The House of the Mountain of Countries."'

And Professor Sayce, in his Hibbert Lectures, is

equally definite. 'As the peak of the Mount of the Deluge (Nizar) was called Ziggurat or temple tower, so, conversely, the Mountain of the World was the name given to a temple Ziggurat at Calah.' 'A fragmentary tablet which gives, as I believe, the Babylonian version of the building of the tower of Babel, especially identifies it with "the illustrious mound."' The name given to the tower of the chief temple at Kis was 'The Illustrious Mountain of Mankind.'

Our last picture of the earthly paradise and world mountain shall be that of the Kingdom of Atlas, for which Plato gathers up just what he requires of tradition, and uses it with the realism of Swift. The successive zones of water and land, and the many-coloured walls, show it to be as real a legend of the heavenly Mount Meru as is the picture of a Buddhist paradise given here for comparison.

We will take first the story told by the Buddha to Ananda of 'The Great King of Glory:'—

'Kasavati was the royal city . . . and on the east and on the west it was twelve leagues in length, and on the north and on the south it was seven leagues in breadth.

'The royal city Kasavati, Ananda, was surrounded by seven ramparts. Of these, one rampart was of gold, and one of silver, and one of beryl, and one of crystal, and one of agate, and one of coral, and one of all kinds of gems.

'To the royal city Kasavati, Ananda, there were four gates; one was of gold, and one of silver, and one of jade, and one of crystal.

'At each gate seven pillars were fixed of the seven precious substances and four times the height of a man. The city was surrounded by seven rows of palm trees; of gold, of silver, and of gems; their fruits were jewels, from which, shaken by the wind, there

arose delightful music. In this city was a palace of righteousness, a league east and west by a half-league north and south, with 84,000 chambers, each of gold, silver, beryl, and crystal; at each door stood a palm tree. The palace was all hung about with a network of bells of gold and silver, the music of which was sweet and intoxicating. There was a lotus lake lined with tiles of gold, silver, beryl, and crystal.

'I was that king, and all these things were mine! See, Ananda, how all these things are past, are ended, have vanished away!' (Rhys Davids, S.B. of East, vol. xi.)

Plato's island of Atlantis had in the centre a plain, in the midst of which was a mountain. Poseidon enclosed the hill all round, making alternate zones of sea and land, larger and smaller, encircling one another; there were two of land and three of water, which he turned as with a lathe out of the centre of the island, equidistant every way.

His eldest son he named Atlas, and from him the whole island and the ocean received the name of Atlantic. In the first place they dug out of the earth whatever was to be found there, mineral as well as metal; and that which is now only a name, and was then something more than a name, orichalcum, was dug out of the earth in many parts of the island . . . also whatever fragrant things there are in the earth, whether roots or herbage, or woods or essences which distil from fruit and flower, grew and thrived in that land. . . . All these that sacred island, which then beheld the light of the sun, brought forth fair and wondrous and in infinite abundance.

'They bridged across the zones and opened waterways from one zone to the other. . . . All this, including the zones and the bridge, they surrounded by a stone wall, on all sides placing towers and gates where the sea passed in.

'One kind of stone was white, another black, and a third red; some of their buildings were simple, but in others they put together different stones, varying the pattern to please the eye, and to be a natural source of delight. The entire circuit of the wall that went round the outermost zone they covered with a coating of brass; and the circuit of the next wall they coated with tin; and the third, which encompassed the citadel, flashed with the red light of orichalcum. The palaces in the interior were constructed on this wise:—In the centre was a holy temple dedicated to Cleito and Poseidon, which remained inaccessible, and was surrounded by an enclosure of gold. Here too was Poseidon's own temple, which was a stadium in length and half a stadium in width, and of a proportionate height, having a strange Asiatic look. All the outside of the temple, with the exception of the pinnacles, they covered with silver, and the pinnacles with gold. In the interior of the temple the roof was of ivory, adorned everywhere with gold, and silver, and orichalcum; and all the other parts of the walls, and pillars, and floor, they lined with orichalcum.

'In the temple they placed statues of gold: there was the god himself standing in a chariot—the charioteer of six winged horses—and of such a size that he touched the roof of the building with his head. . . . Enough of the plan of the royal palace. Leaving the palace and crossing the three harbours outside you come to a wall which began at the sea and went all round; this was everywhere distant fifty stadia from the largest zone or harbour, and enclosed the whole.

'Such was the vast power which the god settled in the lost island of Atlantis. They despised everything but virtue, caring little for their present state of life, and thinking lightly of the possession of gold and

other property, which seemed only a burden to them: neither were they intoxicated by luxury; nor did wealth deprive them of their self-control, but they were sober, and saw clearly that all these goods are increased by virtue and friendship with one another' (Critias Jowett).

'Thou hast been in Eden, the garden of God; every precious stone was thy covering. Thou wast upon the holy mountain of God; thou hast walked up and down in the midst of the stones of fire.'