Click to enlarge

Architecture, Mysticism and Myth, by W.R. Lethaby, [1892], at sacred-texts.com

|

'The altar cell was a dome low-lit, |

WE cannot think of a time when Man had not asked, Where am I? Nor, when he had arrived at an explanation, that it was not set forth by representation; not a definition in a book, or by carefully chosen speech, but dramatically by that parler aux yeux which is an increasing factor in speech as you go backwards in the history of intelligent communication.

If we remember that 'old means not old in chronology, but in structure: that is most archaic which lies nearest to the beginning of human progress considered as a development,' we may roughly put as the beginning of graphic and descriptive astronomy the dance and the story. The dance, on the one hand, becomes a part of ritual, and the story passes into mythology.

Every key applied to custom and mythology unlocks some of their secrets; and Mr Max Müller, Mr Andrew Lang, and Dr Tylor are certainly agreed that to a large extent what is now mythology was

once an explanation of nature. In this view the Odyssey itself is an old and artistic geography, and the stories of Hercules, Theseus, and Jason, astronomy for the young.

We ought at this point to examine rites and ceremonies, savage dances, priestly observance, courtly ceremony, and the pomp of war, the great festivals and games; and in all these things we should find that man, after a certain stage was reached, was ever trying to conform himself to the ritual of nature, so that, like it in some respects, he might share its power and permanence.

But ritual is too wide a subject merely to glance at; we must limit ourselves to things made, or poets’ views of how they should be made. In these the tendency has been universal to embody the natural order: not a plan of the world for science, but as a religious mystery and symbol; as magic amulet, charm, fetish.

Such was the shield of Achilles; and Mr Gladstone, so well is this understood, bases his inquiry as to the Homeric Geography on the description in the Iliad of this work of Hephæstos, the fabricator God. 'On it he formed earth, sky, and sea, the unwearied sun, full moon, and all the signs with which the sky is crowned—Pleiades, Hyads, the might of Orion, and the Bear (which men also call the Wain), it turns there and watches Orion, nor dips it into ocean.' And so on with the whole lovely description comprising the entire Cosmos.

1. The sun, moon, and revolving signs of the heavens.

2. The earth, two cities—one at peace, the other at war; the life of the fields in the round of the year; ploughing, reaping and the vintage, herding of cattle and sheep folds.

3. The dancing place that Dædalus built for fair-haired Ariadne, where they imitated in the circling dance the tortuous way of the labyrinth—a hint on the shield of the under-world.

4. Ocean which flowed round the world beside the outer edge of the thick-made shield.

This making the shield a map of things celestial is followed by Æschylus in the 'Seven against Thebes.' Before the first gate Tydeus bore a shield—

[paragraph continues] And Nonnos gives Bacchus a shield blazoned with the whole celestial system (Dupuis).

In Temple pageantry the sky was often represented by a veil or mantle of purple tissue scintillating with stars, either robing the God, hung before the sanctuary, or covering artificial erections, Asherim, 'The Groves' of Scripture.

Lenormant in his 'Origines,' remarking that a winged oak with a veil thrown over it, 'the tree and the peplos,' was the image by which the Phœnicians figured the universe, citing Pausanias for an actual temple veil of this kind at Gabala in Syria; quotes from Nonnos the description of Harmonia weaving the magnificent web patterned with the images of the whole natural order:—

'Bent over Athene's cunning loom, Harmonia wove a peplos with the shuttle; in the stuff which she wove, she first represented the earth with its omphalos in the centre; around the earth she spread out the sphere of heaven, varied by the figures of the stars. She harmoniously accompanied the earth with the sea that is associated with it, and she painted thereon the rivers, under their image of bulls with men's faces

furnished with horns. Lastly, all along the exterior edge of the well-woven vestment she represented the ocean in a circle enveloping the Universe in its course.'

Josephus states that the veil of Herod's temple was blue, scarlet, white, and purple, embroidered with the constellations of heaven.

The well-known practice of renewing these temple veils yearly agrees with their astronomical significance. The annual procession with the new covering to the Caaba at Mecca, still continues this practice.

When the world was a tree, every tree was in some sort its representation; when a tent or a building, every tent or building: but when the relation was firmly established, there was action and reaction between the symbol and the reality, and ideas taken from one were transferred to the other, until the symbolism became complicated, and only particular buildings would be selected for the symbolic purpose: certain forms were reasoned from the building to the world, and conversely certain thoughts of the universe were expressed in the structure thus set apart as a little world for the House of God—a Temple.

To the Teutonic nations trees were the first temples, as resembling the universe tree, the shelter of the gods: with them, according to Grimm, temple and tree were convertible words.

Pliny says 'trees were the first temples; even at this day the simple rustic of ancient custom dedicates his noblest tree to God;' and in 'Outlines of Primitive Belief' (Keary) it is said, 'Certain it is that, among

people who live in woody lands, we find long continuing the habit of using a tree trunk for the main pillar of the house, of building circular walls round that tree, and sloping the roof down to them from it. Of such kind was the house of our Northern ancestors. . . . All this is mere prosaic fact, but soon we pass on to the region of belief and mythology. The Norsman on the image of his own house fashioned his picture of the entire world. The earth with the heaven for a roof, was to him but a mighty chamber, and likewise had its great supporting tree, passing through the midst and branching far upwards among the clouds.' The general accuracy of this view would seem to be confirmed by the Japanese story given by Sir H. Reid, in which the first home of newly created man was built round the heavenly spear, which formed at once its roof tree and the world axis.

Berosos describes the paintings in the Temple of Belus at Babylon; chaotic rather than cosmic it may be said, but having not any the less a direct reference to the framing of the world:—'There was a time when all was water and darkness, in which monstrous animals were spontaneously engendered: men with two wings, and some with four; with two faces and two heads, the one male and the other female, and with the other features of both sexes united in their single bodies; men with the legs and horns of a goat and the feet of a horse; others with the hind quarters of a horse and the other part a man like the hippo-centaurs. There were also bulls with human heads, dogs with four bodies and fishes’ tails, and other quadrupeds, in which various animal forms were blended, fishes, reptiles, serpents, and all kinds of monsters with the greatest variety in their forms,

monsters whose images we see in the paintings of the temple of Bel at Babylon.'

These composite figures, says Perrot, 'were not a caprice of the artists who made them, but were suggested by a cosmic theory of which they formed, as it were, a plastic embodiment and illustration.' The description of the abominations done in Jerusalem (Ezekiel viii. 10, 11) is a close parallel and confirmation.

Other descriptions of Babylonian temples lead us to see a cosmical symbolism in their structure; that by Apollonius is quoted in a later chapter, and another in an Arab translation of the Nabathean agriculture, relates how the images of the gods throughout the world betook themselves to Babylon, to the temple of the sun, 'to the great golden image suspended between heaven and earth. The sun image stood, they say, in the midst of the temple surrounded by all the images of the world; next to it stood the images of the sun in all countries; then those of the moon; next those of Mars; after them the images of Mercury; then those of Jupiter; after them those of Venus; and last of all, of Saturn.' (Baring Gould, 'Curious Myths.') This was evidently a temple with a dome like the firmament, from which golden sun and planets were suspended, and agrees entirely with the account by Apollonius.

But the buildings of Babylon and their more or less lineal descendants in Persia, all of well-defined planetary symbolism, are considered in later chapter's, so we will pass them for the present with just an extract from that old mine, Maurice's 'Antiquities of India:'—

'Porphyry states that the Mithraic caverns represented the world. According to Eubulus, Zoroaster first of all, among the neighbouring mountains of Persia, consecrated a natural cell, adorned with

flowers and watered with fountains, in honour of Mithra, the father of the universe. For he thought a cavern an emblem of the world fabricated by Mithra; and in this cave were many geographical symbols arranged with the most perfect symmetry and at certain distances, which shadowed out the elements and climates of the world.'

Not to elaborate an interpretation of the Pyramids, which have already had far too many ingenious theories built with their silent stones, and it is better to keep clear of conjecture lest the whole argument becomes a sort of pyramid-inverted. Can we believe that the greatest works ever accomplished by man, with infinite toil and laborious accuracy, in an age when almost every act had a religious significance and a mystical reason, carried no symbol—had no thought and message embodied in their design? And this in a tomb the dwelling of no mere man, but the Pharaoh, son of Ra the Sun. Moreover, there is hardly a sepulchral tablet but has expanded on its top edge the sign of the sky, at times painted blue and dotted with stars. Mr R. Proctor thinks it proved that they had an astrological significance in addition to their use as tombs.

According to Brugsch, the Sun temple at Heliopolis had a sacred sealed chamber in form of a pyramid, called 'Ben-Ben,' in which were kept the two barks of the sun; an inscription gives an account of the visit of a king:—'The arrangement of the House of Stars was completed, the fillets were put on, he was purified with balsam and holy water, and the flowers

were presented to him for the house of the obelisk. He took the flowers, and ascended the stairs to the great window to look upon the Sun god Ra in the house of the obelisk. Thus the king himself stood there. The prince was alone. He drew back the bolt and opened the doors, and beheld his father Ra in the exalted house of the obelisk, and the morning bark of Ra, and the evening bark of Turn. The doors were then shut, the sealing clay was laid on, and the King himself impressed his seal.'

The imagery of the temples and many inscriptions make clear that their intention was to localise their great prototype, the temple of the heavens. The dedicator of an inscription speaks thus of the temple of Neith, the mother of the Sun god Ra: 'Moreover, I informed him (Cambyses) also of the high consequence of the habitation of Neith; it is such as a heaven in all its quarters ('a heaven in its whole plan,' Renouf translates). . . . Moreover, of the high importance of the south chamber, and of the north chamber, of the chamber of the morning Sun Ra, and of the chamber of the evening Sun Turn. These are the mysterious places of all the gods' (Brugsch).

Maspero in his recent book 'Egyptian Archæology' considers at length the constructive and decorative symbolism of the Egyptian temple. 'The temple was built in the likeness of the world, as the world was known to the Egyptians. The earth, as they believed, was a flat and shallow plane, longer than its width; the sky, according to some, extended overhead like an immense iron ceiling, and, according to others, like a shallow vault, As it could not remain suspended in space, without some support, they imagined it to be held in place by four immense

props or pillars. The floor of the temple naturally represented the earth. The columns, and if needful, the four corners of the chambers stood for the pillars. The roof vaulted at Abydos, flat elsewhere, corresponded exactly with the Egyptian idea of the sky. Each of these parts was therefore decorated in consonance with its meaning; those next to the ground were clothed with vegetation. The bases of the columns were surrounded by leaves, and the lower part of the walls were adorned with long stems of lotos or papyrus, in the midst of which animals were occasionally depicted. Bouquets of water plants, emerging from the water, enliven the bottom of the wall space in certain chambers. Elsewhere we find full-blown flowers interspersed with buds or tied together with cords. . . . The ceiling was painted blue, and spangled with five pointed stars painted yellow, occasionally interspersed with the cartouches of the royal founder. The vultures of Nekheb and Uati, the goddesses of the south and north, crowned and armed with divine emblems, hovered above the central nave of the hypostyle halls and on the underside of the lintels of the front doors, above the head of the Great King as he passed through on his way to the sanctuary.'

'At the Ramessium, at Edfou, at Philæ, at Denderah, at Ombos, at Esnah, the depths of the firmament seemed to open to the eyes of the faithful, revealing the dwellers therein. There the celestial ocean poured forth its floods, navigated by the sun and moon, with their attendant escort of planets, constellations, and decans; there also the genii of the months and days passed in long procession. In the Ptolemaic age zodiacs fashioned after Greek models were sculptured side by side with astronomical tables of purely native origin. Finally, the decoration of

the lowest part of the walls and of the ceiling were restricted to a small number of subjects, which were always similar, the most important and varied scenes being suspended as it were between earth and heaven on the sides of the chambers and the Pylons. These scenes illustrated the official relations which subsisted between Egypt and the gods. . . . The sun, travelling from east to west, divided the universe into two worlds—the world of the north and the world of the south. The Temple, like the universe, was double, and an imaginary line, passing through the axis of the sanctuary, divided it into two temples—the temple of the south on the right hand, and the temple of the north on the left. Each chamber was divided, in imitation of the temple, into two halves.'

To pass to the Semitic peoples. Philo Judæus states that the Temple of Solomon was built in imitation of the world fabric, and Josephus gives the same explanation of the symbolism of the Tabernacle. It has been seen in the first chapter how the Tabernacle was the pattern of the universe in small to the early Christian Fathers; and the text of the Psalms would seem to prove that this was the Psalmist's own view: 'And he built his sanctuary like high (palaces), like the earth, which he hath established for ever' (Ps. lviii.).

Often it is not so much the actual earth and visible heavens that were symbolised, as the original celestial world of the golden age—Paradise; but a real, substantial, and geographical Paradise.

Of the Caaba of Mecca—an early Arab temple still preserved in continued use—the story is told, that after Adam and Eve were cast out of Paradise, they came together again near to Mecca. Adam prayed for a shrine 'similar to that at which he had worshipped when in Paradise. The supplication of Adam was

effectual. A tabernacle or temple, formed of radiant clouds, was lowered down by the hands of angels, and placed immediately below its prototype in the celestial paradise. Towards the heaven-descended shrine Adam thenceforth turned in prayer, and round it he daily made seven circuits, in imitation of the rites of the adoring angels.' So much for the symbolism of the Caaba—'the Cube'—of Mecca. Other allied Semitic structures, the small buildings found by Renan in Syria, have this cubical form. So also have later buildings of Roman date, described by Count de Vogüé as 'Kalybes': these are surmounted by cupolas. This accomplished archæologist says: 'The cube is essentially a mystical form, which is found in the cellæ of Egyptian temples and that of Jerusalem; the hemisphere is the image of the celestial vault. We know that the cella of a temple was regarded as the dwelling of the god represented by the statue—a mystic symbol, or an invisible oracle. Originally the sacred edifice was the image of the celestial dwelling, as the symbol which inhabited it was the image of the divine personage. The Etruscan priest who built a sanctuary, traced above in the sky with his wand the foundations which he re-produced on earth—he transported, so to say, upon the earth a part of the sky to make a dwelling for his God. This idea is found in all countries, although it may not be so formally expressed' (La Syrie Centrale).

To the early European races, in the same way, 'the most magnificent temple which the ancients imagined, and which preceded all their notions of buildings made with hands, was the vault of Olympus, in which they supposed the great Jove to reside.' More particularly was this symbolism preserved in later time in the circular structures, the Tholos of Hestia in Greece, and of Vesta in Rome: a form which is

allowed by the latest authorities to represent the heavenly vault.

Plutarch in 'Isis and Osiris' describes a temple of Vesta:—'Numa built a temple of an orbicular form, for the preservation of the sacred fire; intending by the fashion of the edifice to shadow out not so much the earth, or Vesta considered in that character, as the whole universe, in the centre of which the Pythagoreans placed fire, which they called Vesta and Unity.' Ovid in the 'Fasti' gives the same explanation; the temple represented the round earth, 'a reason for its figure worthy of our approval.'

The great rotunda at Rome, the Pantheon, is, of course, the most superb temple in this manner, 143 feet in diameter, with a simple aperture in the dome thirty feet across, through which streams the great beam of the sun. The height to the zenith, from the floor, is equal to the diameter, so that it would just contain a sphere. Of this vast domed expanse, Pliny says, 'quod forma ejus convexa fastigiatum cæli similitudinem ostenderet.' It has been suggested for the plan, a circle with eight great niches, one of which is occupied by the door to the north, that the south niche was intended to be occupied by Phœbus Apollo, and the rest by the Moon and five other planets—Diana, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn.

The ancient Latin custom at the foundation of sacred buildings, in relating them to the heavens, is thus described: 'Templum is the same word as the Greek temenos; for the templum, according to Servius, was any place which was circumscribed and separated by the augurs from the rest of the land by a certain solemn formula. A place thus set apart and hallowed by the augurs was always intended to serve religious purposes, but chiefly for taking the auguria. The place in the heavens within which the observations were

to be made was likewise called templum, as it was marked out and separated from the rest by the staff of the augur. When the augur had defined the templum within which he intended to make his observations, he fixed his tent (tabernaculum), in it, and this tent was likewise called templum or, more accurately, templum minus' (Dr Smith's Dict.).

The Druids had, as a rite, yearly to pull down and rebuild the roof of their temple, 'as a symbol of the destruction and renovation of the world.' The yearly veil, or the rekindled fire, is a much less serious form of the renewal, type and guarantee of the world's continuance.

The poets and romance writers have preserved the tradition of buildings like the world temple even to the Renaissance; the central temple in the Hypnerotomachia is circular, with a dome from which hangs one great orbicular lamp; and the town and temple in Campanella's 'Civitas Solis' is elaborately symbolical. The town was divided into seven great rings named from the seven planets, with four main streets and gateways looking to the points of the compass; the temple in the centre was also circular, and domed. Above the altar, a large globe represented the earth; on the dome were all the stars of heaven from the first to the sixth magnitude, with their names and influences marked, and the meridians and great circles in relation to the altar. The pavement was of precious stones. Seven golden, ever-burning lamps bore the names of the seven planets. Louis XIV. seems to have tried to realise something of this sort at Marley; and according to Mr H. Melville, 'Royal Arch Mason,' in a book entitled 'Veritas,' even the modern ritual of Masonic Lodges is cosmical.

But we have not done with the East and the beginning of history. 'It has ever been accepted as a physical axiom in China that heaven is round and earth is square; and among the relics of Nature worship of old we find the altar of heaven at Pekin round, while the altar of earth is square.' The former is described farther on in Chapter VI. According to Professor Legge, it dates from the twelfth century B.C., and is thus primitive Chinese before Confucius. 'The sovereigns of the Chan dynasty (1152-250 B.C.) worshipped in a building which they called the Hall of Light, which also served the purpose of an audience and council chamber. It was 112 feet square, and surmounted by a dome typical of heaven above and earth beneath' (Giles’ 'Historic China').

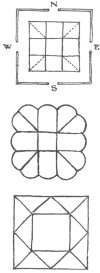

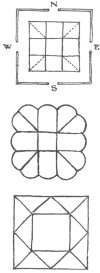

In the old Chinese book the Li-Ki (Sacred Books of the East) there is a long account of the 'Hall of Distinction,' accompanied by a native plan. In it the Emperor as 'Son of Heaven' has to go through an elaborate solar ritual, passing from room to room as the sun passes into the several solar mansions. A large square enclosure surrounds the whole, with four ceremonial gateways (Pailoos) opening to the cardinal points. The building is perfectly square, and divided into three each way, making in all nine apartments, the middle one being called the hall of the centre. The exterior wall of each apartment—three facing each of the four quarters of the heavens—is dedicated to one of the months, the angle rooms being named twice over. The 'hall of the centre' is only occupied for a time between the sixth and seventh month. The 'Son of Heaven’s' progress is also marked by dress and symbolism appropriate to the season.

If we compare this with the Buddhist plan of the world given in Bock's 'Siam,' the reproduction of the pattern of the world will be apparent. The diagram

of the twelve heavenly houses used by astrologers is very similar (see figures).

Click to enlarge |

Sir W. Chambers, in his account of Chinese gardens, with their summer-houses and pavilions, says: 'Some of these are called Mian Ting, or Halls of the Moon, being of prodigious size, and composed each of a vaulted room made in the shape of a hemisphere, the

concave of which is artfully painted in imitation of a nocturnal sky, and pierced with an infinite number of little windows, made to represent the moon and stars, being filled with tinted glass that admits the light in the quantities necessary to spread over the whole interior fabric the pleasing gloom of a fine summer's night. The pavements of these rooms are sometimes laid out in parterres of flowers; but oftenest the bottom is full of clear running water, which falls in rills from the sides of a rock in the centre; many little islands float upon its surface, and move around as the current directs, some of them covered with tables for the banquet, seats, and other objects.'

Of the Taouist temples, Dr Edkins tells us: 'The endeavour is made in these to represent the gods of the religion in their celestial abodes seated on their thrones.' In India the rock-cut caves of Ellora are said to be complete representations of the paradise of Siva; the great props left to support the roof are called 'Sumeru,' after the sky-supporting mountain, the 'Beautiful Meru.'

The Buddhist Stupas or Topes—those nearly solid masses of the form of a bubble floating on water, as an old author has it, or of a bell on a platform, surmounted by umbrella-shaped canopies—would more properly, perhaps, be classed with the solid structures of Babylon and Mexico in Chapter VI., as representing the heavenly regions from without as the mount of heaven, instead of from within, as a dwelling for deity. Asoka, according to the legend, had eighty-four thousand constructed simultaneously: on them every splendour was lavished—gilding, great glass jewels, golden bells; statues of elephants with real tusks guarded the enclosures, and at festivals they were buried in a profusion of flowers. Fa-Hian speaks of one as 700 feet high; but some were only a foot or

two in diameter. Mr A. Lillie, in his 'Buddhism in Christendom,' gives a diagram of a stupa representing the successive zones of the heavens. Professor Beal in the 'Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society,' vol. V., states that the great tope at Sanchi represents heaven and earth, and points out how even the curious Buddhist railing, which surrounds some of these structures,

is of a chessboard pattern, as the enclosing walls of Paradise are described to be; the four great gates in these enclosures are called Torana, which means an ornamental gate or door to the abode of the celestials.

The same author in his little book on Chinese Buddhism remarks: 'Whether it be true or not that a simple idea underlies all rightly-directed efforts of man to raise a building fit for the worship of God,

in this particular Buddhism illustrates the supposed rule. The symbolism of the tope or stupa from the crowning spire of which the (Chinese) pagoda originates, is, like that of all other sacred edifices, intended to figure out an idea of the world or universe ruled over or occupied by one supreme Spirit or Being. This certainly was the meaning of the figure and furniture of the Jewish tabernacle and of the temple. As Josephus says in his 'Antiquities,' Solomon rose up and said, 'O Lord! Thou hast an eternal house, and such as Thou hast created for Thyself out of Thine own work, we know it to be the heaven, and the air, and the earth, and the sea:' it was a symbol of this that Solomon built, so Philo tells us, and Cosmas labours at length to show the same thing. The stupa is a high solid structure based on a square foundation or platform, from which rises into the air a semicircular dome, which is crowned by a square railing, or sometimes a solid cube with eyes on every side. The square platform represents earth, the semicircular dome figures out the air, the railed structure on the top denotes the heaven, where watch the four gods (indicated by eyes). This was the first great effort to describe in stone the idea of the world, or the three worlds, over which the supreme presence of Buddha was supposed to rule; in this stupa were his relics denoting his presence, the only authorised substitute for himself. As the system grew the idea of the universe expanded also, and it was not only earth and air and heaven that had to be represented, but the towering worlds above the heaven, and after that the platforms or plateaux (it is the only word we can use) of heavens extending upwards and towards the eight points of space; hence the symbolism expanded also, and above the cubical structure was erected a high staff with rings or

umbrellas to denote world soaring above world to the uppermost empyrean. Now it is this crowning pole with its rings or umbrellas that originated the idea of the pagoda. Each platform in this structure denotes a world; as they tower upwards in beautifully decreasing size, they offer to the eye an effort of the mind of man to represent the idea of the infinite. On each side of these platforms there are bells and tinkling copper leaves to denote the eternal 'music of the spheres,' and the beautifully carved balustrades and projecting eaves are ever described as proper emblems of the happy beings who enjoy the presence of the Buddhas dwelling in these supreme regions. This is the origin of the pagodas, and there is nothing which gives China its distinctive architectural character so much as these Buddhist structures not used for worship, but to figure out the illimitable nature of the space in which dwells the spiritual essence of all the Buddhas' (Beal).

In the modern Chinese ritual of Buddhism Dr Edkins says, 'Kan (heaven) is the covering let down over an idol, as in the phrase Fo-Kan (a shrine for Buddha), and it here represents the sky as a canopy stretched over the world. Yu (the earth) is the chariot in which the idol sits.' The tooth of Buddha in Ceylon is preserved under nine of these bell-shaped gold and jewelled canopies representing the nine heavens. Buddhist bells in China and Japan are usually ornamented with meridian lines, the sun, and the stars.

In China the tombstones are often the well-known composite symbol consisting of a cube as a base, on it a sphere, then a cone, a crescent, and an inverted pear-shaped apex; on each of the solids are characters signifying earth, air, fire, water, and ether, in the order in which the elements were supposed to be

superimposed. And even the coinage, circular with a square hole, is well-understood as symbolising heaven and earth.

In Christian architecture it is still said at times that the nave and the chancel, divided by the screen, symbolise earth and heaven; and Curzon gives it as the acknowledged significance of the Byzantine Churches with the Berna shut off by the Iconastasis.

Didron tells us that the two or three thousand sculptures of one of the greater French cathedrals of the thirteenth century are stone encyclopædias comprising nature, science, ethics, and history. 'These sculptures, then, are, in the fullest sense of the word, what in the language of the Middle Ages was called the "Image or Mirror of the Universe."' But it is rather the universe of religious ideas than the actual solid built world. The Byzantine scheme preserved more of the original thought: Christ was enthroned at the zenith of the central dome, then zone below zone, were the heavenly powers, the saints, and all. nature, one great chorus of praise.

A Byzantine church in Athens, the Magale Panagia, is described in 'Archæologia' (Vol. I., New Series), and photographs are given of the paintings now destroyed. High in the centre of the dome is the Christ enthroned, with His feet on the mystic wheels, the whole expanse being a deep blue, next comes a series of nine semicircles containing representations of the Orders of the Hierarchy—the Seraphim, the Cherubim, the Thrones, the Dominions, the Virtues, the Powers, the Principalities, the Archangels, the Angels—which respectively rule the nine heavenly zones; the primum mobile, sphere of the fixed stars, and the seven planets. Below these a belt circles the dome, blue of the firmament, set all over with stars

and the twelve signs of the zodiac; to the east is the sun, and to the west the moon; still below these on the walls are the winds, hail, and snow; and still lower mountains, and trees, and the life on the earth, and with all is interwoven passages from the last three Psalms:—

'O praise the Lord of heaven; praise Him in the height. Praise Him, all ye angels of His; praise Him, all His host. Praise Him, sun and moon; praise Him, all ye stars and light. Praise Him, all ye heavens; and ye waters that are above the heavens. Let them praise the Name of the Lord.'