IN the treasure-chamber of the house Odysseus’ great bow was kept. That bow had been given to him by a hero named Iphitus long ago. Odysseus had not taken it with him when he went to the wars of Troy.

To the treasure-chamber Penelope went. She carried in her hand the great key that opened the doors--a key all of bronze with a handle of ivory. Now as she thrust the key into the locks, the doors groaned as a bull groans. She went within, and saw the great bow upon its peg. She took it down and laid it upon her knees, and thought long the man who had bent it.

Beside the bow was its quiver full of bronze-weighted arrows. The servant took the quiver and Penelope took the bow, and they went from the treasure-chamber and into the hall where the wooers were.

When she came in she spoke to the company and said: ‘Lords of Ithaka and of the islands around: You have come here, each desiring that I should wed him. Now the time has come for me to make my choice of a man from amongst you. Here is how I shall make choice.’

‘This is the bow of Odysseus, my lord who is no more. Whosoever amongst you who can bend this bow and shoot an arrow from it through the holes in the backs of twelve axes which I shall have set up, him will I wed, and to his house I will go, forsaking the house of my wedlock, this house so filled with treasure and substance, this house which I shall remember in my dreams.’

As she spoke Telemachus took the twelve axes and set them upright in an even line, so that one could shoot an arrow through the hole that was in the back of each axe-head. Then Eumæus, the old swineherd, took the bow of Odysseus, and laid it before the wooers.

One of the wooers took up the bow and tried to bend it. But he could not bend it, and he laid it down at the doorway with the arrow beside it. The others took up the bow, and warmed it at the fire, and rubbed it with lard to make it more pliable. As they were doing this, Eumæus, the swineherd, and Philœtius, the cattle-herd, passed out of the hall.

Odysseus followed them into the courtyard. He laid a hand on each and said, ‘Swineherd and cattle-herd, I have a word to say to you. But will you keep it to yourselves, the word I say? And first, what would you do to help Odysseus if he should return? Would you stand on his side, or on the side of the wooers? Answer me now from your hearts.’

Said Philœtius the cattle-herd, ‘May Zeus fulfil my wish and bring Odysseus back! Then thou shouldst know on whose side I would stand.’ And Eumæus said, ‘If Odysseus should return I would be on his side, and that with all the strength that is in me.’

When they said this, Odysseus declared himself. Lifting up his hand to heaven he said, ‘I am your master, Odysseus. After twenty years I have come back to my own country, and I find that of all my servants, by you two alone is my homecoming desired. If you need see a token that I am indeed Odysseus, look down on my foot. See there the mark that the wild boar left on me in the days of my youth.’

Straightway he drew the rags from the scar, and the swineherd and the cattle-herd saw it and marked it well. Knowing that it was indeed Odysseus who stood before them, they cast their arms around him and kissed him on the head and shoulders. And Odysseus was moved by their tears, and he kissed their heads and their hands.

As they went back to the hall, he told Eumæus to bring the bow to him as he was bearing it through the hall. He told him, too, to order Eurycleia, the faithful nurse, to bar the doors of the women’s apartment at the end of the hall, and to bid the women, even if they heard a groaning and a din, not to come into the hall. And he charged the cattle-herd Philœtius to bar the gates of the courtyard.

As he went into the hall, one of the wooers, Eurymachus, was striving to bend the bow. As he struggled to do so he groaned aloud:

‘Not because I may not marry Penelope do I groan, but because we youths of to-day are shown to be weaklings beside Odysseus, whose bow we can in no way bend.’

Then Antinous, the proudest of the wooers, made answer and said, ‘Why should we strive to bend the bow to-day? Nay, lay the bow aside, Eurymachus, and let the wine-bearers pour us out a cupful each. In the morning let us make sacrifice to the Archer-god, and pray that the bow be fitted to some of our hands.’

Then Odysseus came forward and said, ‘Sirs, you do well to lay the bow aside for to-day. But will you not put the bow into my hands, that I may try to bend it, and judge for myself whether I have any of the strength that once was mine?’

All the wooers were angry that a seeming beggar should attempt to bend the bow that none of their company were able to bend; Antinous spoke to him sharply and said:

‘Thou wretched beggar! Is it not enough that thou art let into this high hall to pick up scraps, but thou must listen to our speech and join in our conversation? If thou shouldst bend that bow we will make short shrift of thee, I promise. We will put thee on a ship and send thee over to King Echetus, who will cut thee to pieces and give thy flesh to his hounds.’

Old Eumæus had taken up the bow. As he went with it to Odysseus some of them shouted to him, ‘Where art thou going with the bow, thou crazy fellow? Put it down.’ Eumæus was confused by their shouts, and he put down the bow.

Then Telemachus spoke to him and said, ‘Eumæus, beware of being the man who served many masters.’ Eumæus, hearing these words, took it up again and brought it to Odysseus, and put the bow into his hands.

As Odysseus stood in the doorway of the hall, the bow in his hands, and with the arrows scattered at his feet, Eumæus went to Eurycleia, and told her to bar the door of the women’s apartment at the back. Then Philœtius, the cattle-herd, went out of the hall and barred the gates leading out of the courtyard.

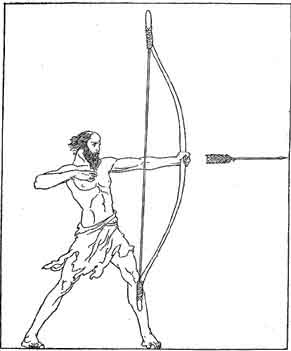

For long Odysseus stood with the bow in his hands, handling it as a minstrel handles a lyre when he stretches a cord or tightens a peg. Then he bent the great bow; he bent it without an effort, and at his touch the bow-string made a sound that was like the cry of a swallow. The wooers seeing him bend that mighty bow felt, every man of them, a sharp pain at the heart. They saw Odysseus take up an arrow and fit it to the string. He held the notch, and he drew the string, and he shot the bronze-weighted arrow straight through the holes in the back of the axe-heads.

|

Saying this he nodded to Telemachus, bending his terrible brows. Telemachus instantly girt his sword upon him and took his spear in his hand. Outside was heard the thunder of Zeus. And now Odysseus had stripped his rags from him and was standing upright, looking a master of men. The mighty bow was in his hands, and at his feet were scattered many bronze-weighted arrows.