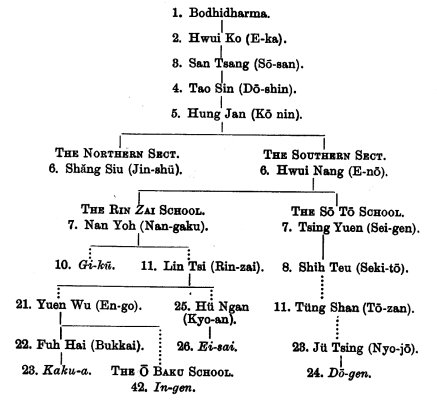

1. The Establishment of the Rin Zai[1] School of Zen in Japan.--The introduction of Zen into the island empire is dated as early as the seventh century;[2] but it was in 1191 that it was first established by Ei-sai, a man of bold, energetic nature. He crossed the sea for China at the age of twenty-eight in 1168, after his profound study of the

[1. The Lin Tsi school was started by Nan Yoh, a prominent disciple of the Sixth Patriarch, and completed by Lin Tsi or Rin Zai.

2 Zen was first introduced into Japan by Do sha (629-700) as early as 653-656, at the time when the Fifth Patriarch just entered his patriarchal career. Do-sho went over to China in 653, and met with Hüen Tsang, the celebrated and great scholar, who taught him the doctrine of the Dharma-laksana. It was Hüen Tsang who advised Do-sho to study Zen under Hwui Man (E-man). After returning home, he built a Meditation Hall for the purpose of practising Zen in the Gan-go monastery, Nara. Thus Zen was first transplanted into Japan by Do-sho, but it took no root in the soil at that time.

Next a Chinese Zen teacher, I Kung (Gi-ku), came over to Japan in about 810, and under his instruction the Empress Danrin, a most enthusiastic Buddhist, was enlightened. She erected a monastery named Dan-rin-ji, and appointed I Kung the abbot of it for the sake of propagating the faith. It being of no purpose, however, I Kung went back to China after some years.

Thirdly, Kaku-a in 1171 went over to China, where he studied Zen under Fuh Hai (Buk-kai), who belonged to the Yang Ki (Yo-gi) school, and came home after three years. Being questioned by the Emperor Taka-kura (1169-1180) about the doctrine of Zen, he uttered no word, but took up a flute and played on it. But his first note was too high to be caught by the ordinary ear, and was gone without producing any echo in the court nor in society at large.]

whole Tripitaka[1] for eight years in the Hi-yei Monastery[2] the then centre of Japanese Buddhism. After visiting holy places and great monasteries, he came home, bringing with him over thirty different books on the doctrine of the Ten-Dai Sect.[3] This, instead of quenching, added fuel to his burning desire for adventurous travel abroad. So he crossed the sea over again in 1187, this time intending to make pilgrimage to India; and no one can tell what might have been the result if the Chinese authorities did not forbid him to cross the border. Thereon he turned his attention to the study of Zen, and after five years' discipline succeeded in getting sanction for his spiritual attainment by the Hü Ngan (Kio-an), a noted master of the Rin Zai school, the then abbot of the monastery of Tien Tung Shan (Ten-do-san). His active propaganda of Zen was commenced soon after his return in 1191 with splendid success at a newly built temple[4] in the province of Chiku-zen. In 1202 Yori-iye, the Shogun, or the real governor of the State at that time, erected the monastery of Ken-nin-ji in the city of Kyo-to, and invited him to proceed to the metropolis. Accordingly he settled himself down in that temple, and taught Zen with his characteristic activity.

[1. The three divisions of the Buddhist canon, viz.:

(1) Sutra-pitaka, or a collection of doctrinal books.

(2) Vinaya-pitaka, or a collection of works on discipline.

(3) Abhidharma-pitaka, or a collection of philosophical and expository works.

2 The great monastery erected in 788 by Sai-cho (767-822), the founder of the Japanese Ten Dai Sect, known as Den Gyo Dai Shi.

3 The sect was named after its founder in China, Chi 1 (538-597), who lived in the monastery of Tien Tai Shan (Ten-dai-san), and was called the Great Teacher of Tien Tai. In 804 Den-gyo went over to China by the Imperial order, and received the transmission of the doctrine from Tao Sui (Do-sui), a patriarch of the sect. After his return he erected a monastery on Mount Hi-yei, which became the centre of Buddhistic learning.

4 He erected the monastery of Sho-fuku-ji in 1195, which is still prospering.]

This provoked the envy and wrath of the Ten Dai and the Shin Gon[1] teachers, who presented memorials to the Imperial court to protest against his propagandism of the new faith. Taking advantage of the protests, Ei-sai wrote a book entitled Ko-zen-go-koku-ron ('The Protection of the State by the Propagation of Zen'), and not only explained his own position, but exposed the ignorance 2 of the protestants. Thus at last his merit was appreciated by the Emperor Tsuchi-mikado (1199-1210), and he was promoted to So Jo, the highest rank in the Buddhist priesthood, together with the gift of a purple robe in 1206. Some time after this he went to the city of Kama-kura, the political centre, being invited by Sane-tomo, the Shogun, and laid the foundation of the so-called Kama-kura Zen, still prospering at the present moment.

2. The Introduction of the So-To School[3] of Zen.--Although the Rin Zai school was, as mentioned above, established by Ei-sai, yet he himself was not a pure Zen teacher, being a Ten Dai scholar as well as an experienced practiser of Mantra. The first establishment of Zen in its

[1. The Shin Gon or Mantra Sect is based on Mahavairocanabhi-sambodhi-sutra, Vajraçekhara-sutra, and other Mantra-sutras. It was established in China by Vajrabodhi and his disciple Amoahavajra, who came from India in 720. Ku kai (774-835), well known as Ko Bo Dai Shi, went to China in 804, and received the transmission of the doctrine from Hwui Kwo (Kei-ka), a, disciple of Amoghavajra. In 806 he came back and propagated the faith almost all over the country. For the detail see 'A Short History of the Twelve Japanese Buddhist Sects' (chap. viii.), by Dr. Nanjo.

2 Sai-cho, the founder of the Japanese Ten Dai Sect, first learned the doctrine of the Northern School of Zen under Gyo-hyo (died in 797), and afterwards he pursued the study of the same faith under Siao Jan in China. Therefore to oppose the propagation of Zen is, for Ten Dai priests, as much as to oppose the founder of their own sect.

3 This school was started by Tsing-Yuen (Sei-gen), an eminent disciple of the Sixth Patriarch, and completed by Tsing Shan (To-zan).]

purest form was done by Do-gen, now known as Jo Yo Dai Shi. Like Ei-sai, he was admitted into the Hi-yei Monastery at an early age, and devoted himself to the study of the Canon. As his scriptural knowledge increased, he was troubled by inexpressible doubts and fears, as is usual with great religious teachers. Consequently, one day he consulted his uncle, Ko-in, a distinguished Ten Dai scholar, about his troubles. The latter, being unable to satisfy him, recommended him Ei-sai, the founder of the new faith. But as Ei-sai died soon afterwards, he felt that he had no competent teacher left, and crossed the sea for China, at the age of twenty-four, in 1223. There he was admitted into the monastery of Tien Tung Shan (Ten-do-san), and assigned the lowest seat in the hall, simply because be was a foreigner. Against this affront he strongly protested. In the Buddhist community, he said, all were brothers, and there was no difference of nationality. The only way to rank the brethren was by seniority, and he therefore claimed to occupy his proper rank. Nobody, however, lent an ear to the poor new-comer's protest, so he appealed twice to the Chinese Emperor Ning Tsung (1195-1224), and by the Imperial order he gained his object.

After four years' study and discipline, he was Enlightened and acknowledged as the successor by his master Jü Tsing (Nyo-jo died in 1228), who belonged to the Tsao Tung (So To) school. He came home in 1227, bringing with him three important Zen books.[1] Some three years he did what Bodhidharma, the Wall-gazing Brahmin, had done seven hundred years before him, retiring to a hermitage.

[1. (1) Pao King San Mei (Ho-kyo-san-mai, 'Precious Mirror Samadhi'), a metrical exposition of Zen, by Tüng Shan (To-zan, 806-869), one of the founders of the So To school. (2) Wu Wei Hien Hüeh (Go-i-ken-ketsu. 'Explanation of the Five Categories'), by Tüng Shan and his disciple Tsao Shan (So-zan). This book shows us how Zen was systematically taught by the authors. (3) Pih Yen Tsih (Heki-gan-shu, 'A Collection and Critical Treatment of Dialogues'), by Yuen Wu.]

at Fuka-kusa, not very far from Kyo-to. Just like Bodhidharma, denouncing all worldly fame and gain, his attitude toward the world was diametrically opposed to that of Ei-sai. As we have seen above, Ei-sai never shunned, but rather sought the society of the powerful and the rich, and made for his goal by every means. But to the Sage of Fuka-kusa, as Do-gen was called at that time, pomp and power was the most disgusting thing in the world. Judging from his poems, be seems to have spent these years chiefly in meditation; dwelling now on the transitoriness of life, now on the eternal peace of Nirvana; now on the vanities and miseries of the world; now listening to the voices of Nature amongst the hills; now gazing into the brooklet that was, as he thought, carrying away his image reflected on it into the world.

3. The Characteristics of Do-gen, the Founder of the Japanese So To Sect.--In the meantime seekers after a new truth gradually began to knock at his door, and his hermitage was turned into a monastery, now known as the Temple of Ko-sho-ji.[1] It was at this time that many Buddhist scholars and men of quality gathered about him but the more popular he became the more disgusting the place became to him. His hearty desire was to live in a solitude among mountains, far distant from human abodes, where none but falling waters and singing birds could disturb his delightful meditation. Therefore he gladly accepted the invitation of a feudal lord, and went to the

[1. It was in this monastery (built in 1236) that Zen was first taught as an independent sect, and that the Meditation Hall was first opened in Japan. Do-gen lived in the monastery for eleven years, and wrote some of the important books. Za-zen-gi ('The Method of Practising the Cross-legged Meditation') was written soon after his return from China, and Ben-do-wa and other essays followed, which are included in his great work, entitled Sho-bo-gen-zo) ('The Eye and Treasury of the Right Law').

province of Echi-zen, where his ideal monastery was built, now known as Ei-hei-ji.[1]

In 1247, being requested by Toki-yori, the Regent General (1247-1263), he came down to Kama-kura, where he stayed half a year and went back to Ei-hei-ji. After some time Toki-yori, to show his gratitude for the master, drew up a certificate granting a large tract of land as the property of Ei-hei-ji, and handed it over to Gen-myo, a disciple of Do-gen. The carrier of the certificate was so pleased with the donation that he displayed it to all his brethren and produced it before the master, who severely reproached him saying: "O, shame on thee, wretch! Thou art -defiled by the desire of worldly riches even to thy inmost soul, just as noodle is stained with oil. Thou canst not be purified from it to all eternity. I am afraid thou wilt bring shame on the Right Law." On the spot Gen-myo was deprived of his holy robe and excommunicated. Furthermore, the master ordered the 'polluted' seat in the Meditation Hall, where Gen-myo was wont to sit, to be removed, and the 'polluted' earth under the seat to be dug out to the depth of seven feet.

In 1250 the ex-Emperor Go-sa-ga (1243-1246) sent a special messenger twice to the Ei-hei monastery to do honour to the master with the donation of a purple robe, but he declined to accept it. And when the mark of distinction was offered for the third time, he accepted it, expressing his feelings by the following verses:

"Although in Ei-hei's vale the shallow waters leap,

Yet thrice it came, Imperial favour deep.

The Ape may smile and laugh the Crane

At aged Monk in purple as insane."

[1. The monastery was built in 1244 by Yoshi-shige (Hatano), the feudal lord who invited Do-gen. He lived in Ei-hei-ji until his death, which took place in 1253. It is still flourishing as the head temple of the So To Sect.]

He was never seen putting on the purple robe, being always clad in black, that was better suited to his secluded life.

4. The Social State of Japan when Zen was established by Ei-sai and Do-gen.--Now we have to observe the condition of the country when Zen was introduced into Japan by Ei-sai and Do-gen. Nobilities that had so long governed the island were nobilities no more. Enervated by their luxuries, effeminated by their ease, made insipient by their debauchery, they were entirely powerless. All that they possessed in reality was the nominal rank and hereditary birth. On the contrary, despised as the ignorant, sneered at as the upstart, put in contempt as the vulgar, the Samurai or military class had everything in their hands. It was the time when Yori-tomo[1] (1148-1199) conquered all over the empire, and established the Samurai Government at Kama-kura. It was the time when even the emperors were dethroned or exiled at will by the Samurai. It was the time when even the Buddhist monks[2] frequently took up arms to force their will. It was the time when Japan's independence was endangered by Kublai, the terror of the world. It was the time when the whole nation was full of martial spirit. It is beyond doubt that to these rising Samurais, rude and simple, the philosophical doctrines of Buddhism, represented by Ten Dai and Shin Gon, were too complicated and too alien to their nature. But in Zen they could find something congenial to their nature, something that touched their chord of sympathy, because Zen was the doctrine of chivalry in a certain sense.

[1. The Samurai Government was first established by Yoritomo, of the Minamoto family, in 1186, and Japan was under the control of the military class until 1867, when the political power was finally restored to the Imperial house.

2 They were degenerated monks (who were called monk-soldiers), belonging to great monasteries such as En-ryaku-ji (Hi-yei), Ko-fuku-ji (at Nara), Mi-i-dera, etc.]

5. The Resemblance of the Zen Monk to the Samurai.--Let us point out in brief the similarities between Zen and Japanese chivalry. First, both the Samurai and the Zen monk have to undergo a strict discipline and endure privation without complaint. Even such a prominent teacher as Ei-sai, for example, lived contentedly in such needy circumstances that on one occasion[1] he and his disciples had nothing to eat for several days. Fortunately, they were requested by a believer to recite the Scriptures, and presented with two rolls of silk. The hungry young monks, whose mouths watered already at the expectation of a long-looked-for dinner, were disappointed when that silk was given to a poor man, who called on Ei-sai to obtain some help. Fast continued for a whole week, when another poor follow came in and asked Ei-sai to give something. At this time, having nothing to show his substantial mark of sympathy towards the poor, Ei-sai tore off the gilt glory of the image of Buddha Bheçajya and gave it. The young monks, bitten both by hunger and by anger at this outrageous act to the object of worship, questioned Ei-sai by way of reproach: "Is it, sir, right for us Buddhists to demolish the image of a Buddha?" "Well," replied Ei-sai promptly, "Buddha would give even his own life for the sake of suffering people. How could he be reluctant to give his halo?" This anecdote clearly shows us self-sacrifice is of first importance in the Zen discipline.

6. The Honest Poverty of the Zen Monk and the Samurai.--Secondly, the so-called honest poverty is a characteristic of both the Zen monk and the Samurai. To get rich by an ignoble means is against the rules of Japanese chivalry or Bushido. The Samurai would rather starve than to live by some expedient unworthy of his dignity. There are many instances, in the Japanese history, of

[1. The incident is told by Do-gen in his Zui-mon-ki.]

Samurais who were really starved to death in spite of their having a hundred pieces of gold carefully preserved to meet the expenses at the time of an emergency; hence the proverb: "The falcon would not feed on the ear of corn, even if he should starve." Similarly, we know of no case of Zen monks, ancient and modern, who got rich by any ignoble means. They would rather face poverty with gladness of heart. Fu-gai, one of the most distinguished Zen masters just before the Restoration, supported many student monks in his monastery. They were often too numerous to be supported by his scant means. This troubled his disciple much whose duty it was to look after the food-supply, as there was no other means to meet the increased demand than to supply with worse stuff. Accordingly, one day the disciple advised Fu-gai not to admit new students any more into the monastery. Then the master, making no reply, lolled out his tongue and said: "Now look into my mouth, and tell if there be any tongue in it." The perplexed disciple answered affirmatively. "Then don't bother yourself about it. If there be any tongue, I can taste any sort of food." Honest poverty may, without exaggeration, be called one of the characteristics of the Samurais and of the Zen monks; hence a proverb: " The Zen monk has no money, moneyed Monto[1] knows nothing."

7. The Manliness of the Zen Monk and of the Samurai.--Thirdly, both the Zen monk and the Samurai were distinguished by their manliness and dignity in manner, sometimes amounting to rudeness. This is due partly to the hard discipline that they underwent, and partly to the mode of instruction. The following story,[2] translated by Mr. D. Suzuki, a friend of mine, may well exemplify our statement:

[1. The priest belonging to Shin Shu, who are generally rich.

2. The Journal of the Pali Text Society, 1906-1907.]

When Rin-zai[1]was assiduously applying himself to Zen discipline under Obak (Huang Po in Chinese, who died 850), the head monk recognized his genius. One day the monk asked him how long he had been in the monastery, to which Rin-zai replied: 'Three years.' The elder said: 'Have you ever approached the master and asked his instruction in Buddhism?' Rin-zai said: 'I have never done this, for I did not know what to ask.' 'Why, you might go to the master and ask him what is the essence of Buddhism?'

"Rin-zai, according to this advice, approached Obak and repeated the question, but before he finished the master gave him a slap.

"When Rin-zai came back, the elder asked how the interview went. Said Rin-zai: 'Before I could finish my question the master slapped me, but I fail to grasp its meaning.' The elder said: 'You go to him again and ask the same question.' When he did so, he received the same response from the master. But Rin-zai was urged again to try it for the third time, but the outcome did not improve.

"At last he went to the elder, and said In obedience to your kind suggestion, I have repeated my question three times, and been slapped three times. I deeply regret that, owing to my stupidity, I am unable to comprehend the hidden meaning of all this. I shall leave this place and go somewhere else.' Said the elder: 'If you wish to depart, do not fail to go and see the master to say him farewell.'

"Immediately after this the elder saw the master, and said: 'That young novice, who asked about Buddhism three times, is a remarkable fellow. When he comes to take leave of you, be so gracious as to direct him properly. After a hard training, he will prove to be a great master,

[1. Lin Tsi, the founder of the Lin Tsi school.]

and, like a huge tree, he will give a refreshing shelter to the world.'

"When Rin-zai came to see the master, the latter advised him not to go anywhere else. but to Dai-gu (Tai-yu) of Kaoan, for he would be able to instruct him in the faith.

"Rin-zai went to Dai-gu, who asked him whence he came. Being informed that he was from Obak, Dai-gu further inquired what instruction he had under the master. Rin-zai answered: 'I asked him three times about the essence of Buddhism, and he slapped me three times. But I am yet unable to see whether I had any fault or not.' Dai-gu said: 'Obak was tender-hearted even as a dotard, and you are not warranted at all to come over here and ask me whether anything was faulty with you.'

"Being thus reprimanded, the signification of the whole affair suddenly dawned upon the mind of Rin-zai, and he exclaimed: 'There is not much, after all, in the Buddhism of Obak.' Whereupon Dai-gu took hold of him, and said: 'This ghostly good-for-nothing creature! A few minutes ago you came to me and complainingly asked what was wrong with you, and now boldly declare that there is not much in the Buddhism of Obak. What is the reason of all this? Speak out quick! speak out quick!' In response to this, Rin-zai softly struck three times his fist at the ribs of Dai-gu. The latter then released him, saying: 'Your teacher is Obak, and I will have nothing to do with you.'

"Rin-zai took leave of Dai-gu and came back to Obak, who, on seeing him come, exclaimed: 'Foolish fellow! what does it avail you to come and go all the time like this?' Rin-zai said: 'It is all due to your doting kindness.'

"When, after the usual salutation, Rin-zai stood by the side of Obak, the latter asked him whence he had come this time. Rin-zai answered: "In obedience to your kind instruction, I was with Dai-gu. Thence am I come.'

And he related, being asked for further information, all that had happened there.

"Obak said: 'As soon as that fellow shows himself up here, I shall have to give him a good thrashing.' 'You need not wait for him to come; have it right this moment,' was the reply; and with this Rin-zai gave his master a slap on the back.

"Obak said: 'How dares this lunatic come into my presence and play with a tiger's whiskers?' Rin-zai then burst out into a Ho,[1] and Obak said: 'Attendant, come and carry this lunatic away to his cell.'"

8. The Courage and the Composure of Mind of the Zen Monk and of the Samurai.--Fourthly, our Samurai encountered death, as is well known, with unflinching courage. He would never turn back from, but fight till his last with, his enemy. To be called a coward was for him the dishonour worse than death itself. An incident about Tsu Yuen (So-gen), who came over to Japan in 1280, being invited by Toki-mune[2] (Ho-jo), the Regent General, well illustrates how much Zen monks resembled our Samurais. The event happened when he was in China, where the invading army of Yuen spread terror all over the country. Some of the barbarians, who crossed the border of the State of Wan, broke into the monastery of Tsu Yuen, and threatened to behead him. Then calmly sitting down, ready to meet his fate, he composed the following verses

"The heaven and earth afford me no shelter at all;

I'm glad, unreal are body and soul.

Welcome thy weapon, O warrior of Yuen! Thy trusty steel,

That flashes lightning, cuts the wind of Spring, I feel."

[1. A loud outcry, frequently made use of by Zen teachers, after Rin-zai. Its Chinese pronunciation is 'Hoh,' and pronounced 'Katsu' in Japanese, but 'tsu' is not audible.

2. A bold statesman and soldier, who was the real ruler of Japan 1264-1283.]

This reminds us of Sang Chao[1] (So-jo), who, on the verge of death by the vagabond's sword, expressed his feelings in the follow lines:

"In body there exists no soul.

The mind is not real at all.

Now try on me thy flashing steel,

As if it cuts the wind of Spring, I feel."

The barbarians, moved by this calm resolution and dignified air of Tsu Yuen, rightly supposed him to be no ordinary personage, and left the monastery, doing no harm to him.

9. Zen and the Regent Generals of the Ho-Jo Period.--No wonder, then, that the representatives of the Samurai class, the Regent Generals, especially such able rulers as Toki-yori, Toki-mune, and others noted for their good administration, of the Ho-jo period (1205-1332) greatly favoured Zen. They not only patronized the faith, building great temples[2] and inviting best Chinese Zen teachers.[3]

[1. The man was not a pure Zen master, being a disciple of Kumarajiva, the founder of the San Ron Sect. This is a most remarkable evidence that Zen, especially the Rin Zan school, was influenced by Kumarajiva and his disciples. For the details of the anecdote, see E-gen.

2. To-fuku-ji, the head temple of a sub-sect of the Rin Zai under the same name, was built in 1243. Ken-cho-ji, the head temple of a subsect of the Rin Zai under the same name, was built in 1253. En-gaku ji, the head temple of a sub-sect of the Rin Zai under the same name, was built in 1282. Nan-zen-ji, the head temple of a sub-sect of the Rin Zai under the same name, was erected in 1326.

3. Tao Lung (Do-ryu), known as Dai-kaku Zen-ji, invited by Tokiyori, came over to Japan in 1246. He became the founder of Ken-cho-ji-ha, a sub-sect of the Rin Zai, and died in 1278. Of his disciples, Yaku-o was most noted, and Yaku-o's disciple, Jaku-shitsu, became the founder of Yo-genji-ha, another sub-sect of the Rin Zai. Tsu Yuen (So-gen), known as Buk-ko-koku-shi, invited by Toki-mune, crossed the sea in 1280, became the founder of En-gaku-ji-ha (a sub-sect of the Rin Zai), and died in 1286. Tsing Choh (Sei-setsu), invited by Taka-toki, came in 1327, and died in 1339. Chu Tsun (So-shun) came in 1331, and died in 1336. Fan Sien (Bon-sen) came together with Chu Tsun, and died in 1348. These were the prominent Chinese teachers of that time.]

but also lived just as Zen monks, having the head shaven, wearing a holy robe, and practising cross-legged Meditation. Toki-yori (1247-1263), for instance, who entered the monastic life while be was still the real governor of the country, led as simple a life, as is shown in his verse, which ran as follows:

"Higher than its bank the rivulet flows;

Greener than moss tiny grass grows.

No one call at my humble cottage on the rock,

But the gate by itself opens to the Wind's knock."

Toki-yori attained to Enlightenment by the instruction of Do-gen and Do-ryu, and breathed his last calmly sitting cross-legged, and expressing his feelings in the following lines:

"Thirty-seven of years,

Karma mirror stood high;

Now I break it to pieces,

Path of Great is then nigh."

His successor, Toki-mune (1264-1283), a bold statesman and soldier, was no less of a devoted believer in Zen. Twice he beheaded the envoys sent by the great Chinese conqueror, Kublai, who demanded Japan should either surrender or be trodden under his foot. And when the alarming news of the Chinese Armada's approaching the land reached him, be is said to have called on his tutor, Tsu Yuen, to receive the last instruction. "Now, reverend sir," said. he, "an imminent peril threatens the land." "How art thou going to encounter it?" asked the master. Then Toki-mune burst into a thundering Ka with all his might to show his undaunted spirit in encountering the approaching enemy. "O, the lion's roar!" said Tsu Yuen.

"Thou art a genuine lion. Go, and never turn back." Thus encouraged by the teacher, the Regent General sent out the defending army, and successfully rescued the state from the mouth of destruction, gaining a splendid victory over the invaders, almost all of whom perished in the western seas.

10. Zen after the Downfall of the Ho-Jo Regency.--Towards the end of the Ho-Jo period,[1] and after the downfall of the Regency in 1333, sanguinary battles were fought between the Imperialists and the rebels. The former, brave and faithful as they were, being outnumbered by the latter, perished in the field one after another for the sake of the ill-starred Emperor Go-dai-go (1319-1338), whose

[1. Although Zen was first favoured by the Ho-jo Regency and chiefly prospered at Kama-kura, yet it rapidly began to exercise its influence on nobles and Emperors at Kyo-to. This is mainly due to the activity of En-ni, known as Sho-Ichi-Koku-Shi (1202-1280), who first earned Zen under Gyo-yu, a disciple of Ei-sai, and afterwards went to China, where he was Enlightened under the instruction of Wu Chun, of the monastery of King Shan. After his return, Michi-iye (Fuji-wara), a powerful nobleman, erected for him To-fuku-ji in 1243, and he became the founder of a sub-sect of the Rin Zai, named after that monastery. The Emperor Go-saga (1243-1246), an admirer of his, received the Moral Precepts from him, One of his disciples, To-zan, became the spiritual adviser of the Emperor Fushi-mi (1288-1298), and another disciple, Mu kwan, was created the abbot of the monastery of Nan-zen-ji by the Emperor Kame-yama (1260-1274), as the founder of a sub-sect of the Rin Zai under the same name.

Another teacher who gained lasting influence on the Court is Nan-po, known as Dai-O-Koku-Shi (1235-1308), who was appointed the abbot of the monastery of Man-ju-ji in Kyo to by the Emperor Fushi-mi. One of his disciples, Tsu-o, was the spiritual adviser to both the Emperor Hana-zono (1308-1318) and the Emperor Go-dai-go. And another disciple, Myo-cho, known as Dai-To-Koku-Shi (1282-1337), also was admired by the two Emperors, and created the abbot of Dai-toku-ji, as the founder of a sub-sect of the Rin Zai under the same name. It was for Myo-cho's disciple, Kan-zan (1277 1360), that the Emperor Hana-zono turned his detached palace into a monastery, named Myo-shin-ji, the head temple of a sub-sect of the Rin Zai under the same name.]

eventful life ended in anxiety and despair. It was at this time that Japan gave birth to Masa-shige (Kusu-noki), an able general and tactician of the Imperialists, who for the sake of the Emperor not only sacrificed himself and his brother, but by his will his son and his son's successor died for the same cause, boldly attacking the enemy whose number was overwhelmingly great. Masa-shige's loyalty, wisdom, bravery, and prudence are not merely unique in the history of Japan, but perhaps in the history of man. The tragic tale about his parting with his beloved son, and his bravery shown at his last battle, never fail to inspire the Japanese with heroism. He is the best specimen of the Samurai class. According to an old document,[1] this Masa-shige was the practiser of Zen, and just before his last battle he called on Chu Tsun (So-shun) to receive the final instruction. "What have I to do when death takes the place of life?" asked Masa-shige. The teacher replied:

"Be bold, at once cut off both ties,

The drawn sword gleams against the skies."

Thus becoming, as it were, an indispensable discipline for the Samurai, Zen never came to an end with the Ho-jo period, but grew more prosperous than before during the reign[2] of the Emperor Go-dai-go, one of the most enthusiastic patrons of the faith.

[1. The event is detailed at length in a life of So-shun, but some historians suspect it to be fictitious. This awaits a further research.

2. As we have already mentioned, Do-gen, the founder of the Japanese So To Sect, shunned the society of the rich and the powerful, and led a secluded life. In consequence his sect did not make any rapid progress until the Fourth Patriarch of his line, Kei-zan (1268-1325) who, being of energetic spirit, spread his faith with remarkable activity, building many large monasteries, of which Yo-ko-ji, in the province of No-to, So-ji-ji (near Yokohama), one of the head temples of the sect, are well known. One of his disciples, Mei ho (1277-1350), propagated the faith in the northern provinces; while another disciple, Ga-san (1275-1365), being a greater character, brought up more than thirty distinguished disciples, of whom Tai-gen, Tsu-gen, Mu-tan, Dai-tetsu, and Jip-po, are best known. Tai-gen (died 1370) and big successors propagated the faith over the middle provinces, while Tsu-gen (1332-1391) and his successors spread the sect all over the north-eastern and south-western provinces. Thus it is worthy of our notice that most of the Rin Zai teachers confined their activities within Kamakura and Kyo-to, while the So To masters spread the faith all over the country.]

The Shoguns of the Ashi-kaga period (1338-1573) were not less devoted to the faith than the Emperors who succeeded the Emperor Go-dai-go. And even Taka-uji (1338-1357), the notorious founder of the Shogunate, built a monastery and invited So-seki,[1] better known as Mu-So-Koku-Shi, who was respected as the tutor by the three successive Emperors after Go-dai-go. Taka-uji's example was followed by all succeeding Shoguns, and Shogun's example was followed by the feudal lords and their vassals. This resulted in the propagation of Zen throughout the country. We can easily imagine how Zen was prosperous in these days from the splendid monasteries[2] built at this period, such as the Golden Hall Temple and the Silver Hall Temple that still adorn the fair city of Kyo-to.

11. Zen in the Dark Age.--The latter half of the Ashikaga period was the age of arms and bloodshed. Every day the sun shone on the glittering armour of marching

[1. So-seki (1276-1351) was perhaps the greatest Zen master of the period. Of numerous monasteries built for him, E-rin-ji, in the province of Kae, and Ten-ryu-ji, the head temple of a sub-sect of the Rin Zai under the same name, are of importance, Out of over seventy eminent disciples of his, Gi-do (1365-1388), the author of Ku-ge-shu; Shun-oku (1331-1338), the founder of the monastery of So-koku-ji, the head temple of a sub-sect of the Rin Zai under the same name; and Zek-kai (1337-1405), author of Sho-ken-shu, are best known.

2 Myo-shin-ji was built in 1337 by the Emperor Hana-zono; Ten-ryu-ji was erected by Taka-uji, the first Shogun of the period, in 1344; So-koku-ji by Yosh-imitsu, the third Shogun, in 1385; Kin-Kaku-ji, or Golden Hall Temple, by the same Shogun, in 1397; Gin-kaku-ji, or Silver Hall Temple, by Yoshi-masa, the eighth Shogun, in 1480.]

soldiers. Every wind sighed over the lifeless remains of the brave. Everywhere the din of battle resounded. Out of these fighting feudal lords stood two champions. Each of them distinguished himself as a veteran soldier and tactician. Each of them was known as an experienced practiser of Zen. One was Haru-nobu[1] (Take-da, died in 1573), better known by his Buddhist name, Shin-gen. The other was Teru-tora[2] (Uye-sugi, died in 1578), better known by his Buddhist name, Ken-shin. The character of Shin-gen can be imagined from the fact that he never built any castle or citadel or fortress to guard himself against his enemy, but relied on his faithful vassals and people; while that of Ken-shin, from the fact that he provided his enemy, Shin-gen, with salt when the latter suffered from want of it, owing to the cowardly stratagem of a rival lord. The heroic battles waged by these two great generals against each other are the flowers of the Japanese war-history. Tradition has it that when Shin-gen's army was put to rout by the furious attacks of Ken-shin's troops, and a single warrior mounted on a huge charger rode swiftly as a sweeping wind into Shin-gen's head-quarters, down came a blow of the heavy sword aimed at Shin-gen's forehead, with a question expressed in the technical terms of Zen: "What shalt thou do in such a state at such a moment?" Having no time to draw his sword, Shin-gen parried it with his war-fan, answering simultaneously in Zen words: "A flake of snow on the red-hot furnace!" Had not his attendants come to the rescue Shin-gen's life might have gone as 'a flake of snow on the red-hot furnace.' Afterwards the horseman was known to have been Ken-shin himself. This tradition

[1. Shin-gen practised Zen under the instruction of Kwai-sen, who was burned to death by Nobu-naga (O-da) in 1582. See Hon-cho-ko-so-den.

2 Ken-shin learned Zen under Shu-ken, a So Ta master. See To-jo-ren-to-roku.]

shows us how Zen was practically lived by the Samurais of the Dark Age.

Although the priests of other Buddhist sects had their share in these bloody affairs, as was natural at such a time, yet Zen monks stood aloof and simply cultivated their literature. Consequently, when all the people grew entirely ignorant at the end of the Dark Age, the Zen monks were the only men of letters. None can deny this merit of their having preserved learning and prepared for its revival in the following period.[1]

12. Zen under the Toku-gana Shogunate.--Peace was at last restored by Iye-yasu, the founder of the Toku-gana Shogunate (1603-1867). During this period the Shogunate gave countenance to Buddhism on one hand, acknowledging it as the state religion, bestowing rich property to large monasteries, making priests take rank over common people, ordering every householder to build a Buddhist altar in his house; while, on the other hand, it did everything to extirpate Christianity, introduced in the previous period (1544). All this paralyzed the missionary spirit of the Buddhists, and put all the sects in dormant state. As for Zen[2] it was

[1. After the introduction of Zen into Japan many important books were written, and the following are chief doctrinal works: Ko-zen-go-koku-ron, by Ei-sai; Sho bo-gen-zo; Gaku-do-yo-zin-shu; Fu-kwan-za-zen-gi; Ei-hei-ko-roku, by Do-gen; Za-zen-yo-zin-ki; and Den-ko-roku, by Kei-zan.

2 The So To Sect was not wanting in competent teachers, for it might take pride in its Ten-kei (1648-1699), whose religious insight was unsurpassed by any other master of the age; in its Shi getsu, who was a commentator of various Zen books, and died 1764; in its Men-zan (1683-1769), whose indefatigable works on the exposition of So To Zen are invaluable indeed; and its Getsu-shu (1618-1696) and Man-zan (1635-1714), to whose labours the reformation of the faith is ascribed. Similarly, the Rin Zai Sect, in its Gu-do (1579-1661); in its Isshi (1608-1646); in its Taku-an (1573-1645), the favourite tutor of the third Shogun, Iye-mitsu; in its Haku-in (1667-1751), the greatest of the Rin Zai masters of the day, to whose extraordinary personality and labour the revival of the sect is due; and its To-rei (1721-1792), a learned disciple of Haku-in. Of the important Zen books written by these masters, Ro-ji-tan-kin, by Ten-kei; Men-zan-ko-roku, by Men-zan; Ya-sen-kwan-wa, Soku-ko-roku, Kwai-an-koku-go, Kei-so-doku-zui, by Haku-in; Shu-mon-mu-jin-to-ron, by To-rei, are well known.]

still favoured by feudal lords and their vassals, and almost all provincial lords embraced the faith.

It was about the middle of this period that the forty-seven vassals of Ako displayed the spirit of the Samurai by their perseverance, self-sacrifice, and loyalty, taking vengeance on the enemy of their deceased lord. The leader of these men, the tragic tales of whom can never be told or heard without tears, was Yoshi-o (O-ishi died 1702), a believer of Zen,[1] and his tomb in the cemetery of the temple of Sen-gaku-ji, Tokyo, is daily visited by hundreds of his admirers.

Most of the professional swordsmen forming a class in these days practised Zen. Mune-nori[2] (Ya-gyu), for instance, established his reputation by the combination of Zen and the fencing art. The following story about Boku-den (Tsuka-hara), a great swordsman, fully illustrates this tendency:

"On a certain occasion Boku-den took a ferry to cross over the Yabase in the province of Omi. There was among the passengers a Samurai, tall and square-shouldered, apparently an experienced fencer. He behaved rudely toward the fellow-passengers, and talked so much of his own dexterity in the art that Boku-den, provoked by his brag, broke silence. 'You seem, my friend, to practise the art in order to conquer the enemy, but I do it in order not to be conquered,' said Boku-den. 'O monk,' demanded the man, as Boku-den was clad like a Zen monk, 'what school of swordsmanship do you belong to?' Well, mine is the

[1. See "Zen Shu," No. 151.

2 He is known as Ta-jima, who practised Zen under Taku-an.]

Conquering-enemy-without-fighting-school.' 'Don't tell a fib, old monk. If you could conquer the enemy without fighting, what then is your sword for?' 'My sword is not to kill, but to save,' said Boku-den, making use of Zen phrases; 'my art is transmitted from mind to mind.' 'Now then, come, monk,' challenged the man, 'let us see, right at this moment, who is the victor, you or I.' The gauntlet was picked up without hesitation. 'But we must not fight,' said Boku-den, 'in the ferry, lest the passengers should be hurt. Yonder a small island you see. There we shall decide the contest.' To this proposal the man agreed, and the boat was pulled to that island. No sooner had the boat reached the shore than the man jumped over to the land, and cried: 'Come on, monk, quick, quick!' Boku-den, however, slowly rising, said: 'Do not hasten to lose your head. It is a rule of my school to prepare slowly for fighting, keeping the soul in the abdomen.' So saying he snatched the oar from the boatman and rowed the boat back to some distance, leaving the man alone, who, stamping the ground madly, cried out: 'O, you fly, monk, you coward. Come, old monk!' 'Now listen,' said Boku-den, 'this is the secret art of the Conquering-enemy-without-fighting-school. Beware that you do not forget it, nor tell it to anybody else.' Thus, getting rid of the brawling fellow, Boku-den and his fellow-passengers safely landed on the opposite shore."[1]

The O Baku School of Zen was introduced by Yin Yuen (In-gen) who crossed the sea in 1654, accompanied by many able disciples.[2] The Shogunate gave him a tract of land at Uji, near Kyo-to, and in 1659 he built there a monastery

[1. Shi-seki-shu-ran.

2 In-gen (1654-1673) came over with Ta-Mei (Dai-bi, died 1673), Hwui Lin (E-rin died 1681), Tuh Chan (Doku-tan, died 1706), and others. For the life of In-gen: see Zoku-ko-shu-den and Kaku-shu-ko-yo.]

noted for its Chinese style of architecture, now known as O-baku-san. The teachers of the same school[1] came one after another from China, and Zen[2] peculiar to them, flourished a short while.

[1. Tsih Fei (Soku-hi died 1671), Muh Ngan (Moku-an died 1684), Kao Tsüen (Ko-sen died 1695), the author of Fu-so-zen-rin-so-bo-den, To-koku-ko-so-den, and Sen-un-shu, are best known.

2 This is a sub-sect of the Rin Zai School, as shown in the following table:

TABLE OF THE TRANSMISSION OF ZEN FROM CHINA. TO JAPAN.

The O Baku School is the amalgamation of Zen and the worship of Amitabha, and different from the other two schools. The statistics for 1911 give the following figures:

|

|

The Number of Temples |

The Number of Teachers |

|

The So To School |

14,255 |

9,576 |

|

The Rin Zai School |

6,128 |

4,523 |

|

The O Baku School |

546 |

349 |

]

It was also in this period that Zen gained a great influence on the popular literature characterized by the shortest form of poetical composition. This was done through the genius of Ba-sho,[1] a great literary man, recluse and traveller, who, as his writings show us, made no small progress in the study of Zen. Again, it was made use of by the teachers of popular [2] ethics, who did a great deal in the education of the lower classes. In this way Zen and its peculiar taste gradually found its way into the arts of peace, such as literature, fine art, tea-ceremony, cookery, gardening, architecture, and at last it has permeated through every fibre of Japanese life.

13. Zen after the Restoration.--After the Restoration of the Mei-ji (1867) the popularity of Zen began to wane, and for some thirty years remained in inactivity; but since the Russo-Japanese War its revival has taken place. And now it is looked upon as an ideal faith, both for a nation full of hope and energy, and for a person who has to fight his own way in the strife of life. Bushido, or the code of chivalry, should be observed not only by the soldier in the battle-field, but by every citizen in the struggle for existence. If a person be a person and not a beast, then he must be a Samurai-brave, generous, upright, faithful, and manly, full of self-respect and self-confidence, at the same time full of the spirit of self-sacrifice. We can find an incarnation of Bushido in the late General Nogi, the hero of Port

[1. He (died 1694) learned Zen under a contemporary Zen master (Buccho), and is said to have been enlightened before his reformation of the popular literature.

2 The teaching was called Shin-gaku, or the 'learning of mind.' It was first taught by Bai-gan (Ishi-da), and is the reconciliation of Shintoism and Buddhism with Confucianism. Bai-gan and his successors practised Meditation, and were enlightened in their own way. Do-ni (Naka-zawa, died 1803) made use of Zen more than any other teacher.]

Arthur, who, after the sacrifice of his two sons for the country in the Russo-Japanese War, gave up his own and his wife's life for the sake of the deceased Emperor. He died not in vain, as some might think, because his simplicity, uprightness, loyalty, bravery, self-control, and self-sacrifice, all combined in his last act, surely inspire the rising generation with the spirit of the Samurai to give birth to hundreds of Nogis. Now let us see in the following chapters what Zen so closely connected with Bushido teaches us.